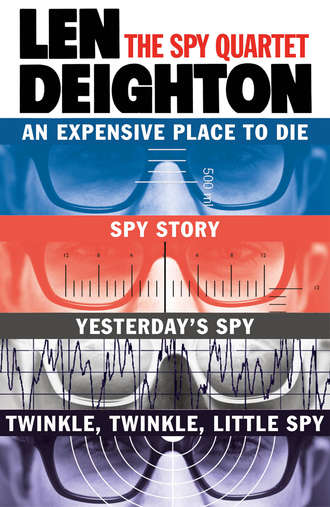

The Spy Quartet: An Expensive Place to Die, Spy Story, Yesterday’s Spy, Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

‘How do you know what makes sense?’ said Datt. ‘I’m arranging your movements, not this fool; how can we trust him? He admits this task is for the Americans.’

‘It makes sense,’ said Kuang again. ‘Hudson’s information is genuine. I can tell: it fills out what I learnt from that incomplete set of papers you passed to me last week. If the Americans want me to have the information, then they must want it to be taken back home.’

‘Can’t you see that they might want to capture you for interrogation?’ said Datt.

‘Rubbish!’ I interrupted. ‘I could have arranged that at any time in Paris without risking Hudson out here in the middle of nowhere.’

‘They are probably waiting down the road,’ said Datt. ‘You could be dead and buried in five minutes. Out here in the middle of the country no one would hear, no one would see the diggings.’

‘I’ll take that chance,’ said Kuang. ‘If he can get Hudson into France on false papers, he can get me out.’

I watched Hudson, fearful that he would say I’d done no such thing for him, but he nodded sagely and Kuang seemed reassured.

‘Come with us,’ said Hudson, and Kuang nodded agreement. The two scientists seemed to be the only ones in the room with any mutual trust.

I was reluctant to leave Maria but she just waved her hand and said she’d be all right. She couldn’t take her eyes off Jean-Paul’s body.

‘Cover him, Robert,’ said Datt.

Robert took a table-cloth from a drawer and covered the body. ‘Go,’ Maria called again to me, and then she began to sob. Datt put his arm around her and pulled her close. Hudson and Kuang collected their data together and then, still waving the gun around, I showed them out and followed.

As we went across the hall the old woman emerged carrying a heavily laden tray. She said, ‘There’s still the poulet sauté chasseur.’

‘Vive le sport,’ I said.

31

From the garage we took the camionette – a tiny grey corrugated-metal van – because the roads of France are full of them. I had to change gear constantly for the small motor, and the tiny headlights did no more than probe the hedgerows. It was a cold night and I envied the warm grim-faced occupants of the big Mercs and Citroëns that roared past us with just a tiny peep of the horn, to tell us they had done so.

Kuang seemed perfectly content to rely upon my skill to get him out of France. He leaned well back in the hard upright seat, folded his arms and closed his eyes as though performing some oriental contemplative ritual. Now and again he spoke. Usually it was a request for a cigarette.

The frontier was little more than a formality. The Paris office had done us proud: three good British passports – although the photo of Hudson was a bit dodgy – over twenty-five pounds in small notes (Belgian and French), and some bills and receipts to correspond to each passport. I breathed more easily after we were through. I’d done a deal with Loiseau so he’d guaranteed no trouble, but I still breathed more easily after we’d gone through.

Hudson lay flat upon some old blankets in the rear. Soon he began to snore. Kuang spoke.

‘Are we going to an hotel or are you going to blow one of your agents to shelter me?’

‘This is Belgium,’ I said. ‘Going to an hotel is like going to a police station.’

‘What will happen to him?’

‘The agent?’ I hesitated. ‘He’ll be pensioned off. It’s bad luck but he was the next due to be blown.’

‘Age?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘And you have someone better in the area?’

‘You know we can’t talk about that,’ I said.

‘I’m not interested professionally,’ said Kuang. ‘I’m a scientist. What the British do in France or Belgium is nothing to do with me, but if we are blowing this man I owe him his job.’

‘You owe him nothing,’ I said. ‘What the hell do you think this is? He’ll be blown because it’s his job. Just as I’m conducting you because that’s my job. I’m doing it as a favour. You owe no one anything, so forget it. As far as I’m concerned you are a parcel.’

Kuang inhaled deeply on his cigarette, then removed it from his mouth with his long delicate fingers and stubbed it into the ashtray. I imagined him killing Annie Couzins. Passion or politics? He rubbed the tobacco shreds from his fingertips like a pianist practising trills.

As we passed through the tightly shuttered villages the rough pavé hammered the suspension and bright-eyed cats glared into our lights and fled. One a little slower than the others had been squashed as flat as an ink blot. Each successive set of wheels contributed a new pattern to the little tragedy that morning would reveal.

I had the camionette going at its top speed. The needles were still and the loud noise of the motor held a constant note. Everything was unchanging except a brief fusillade of loose gravel or the sudden smell of tar or the beep of a faster car.

‘We are near to Ypres,’ said Kuang.

‘This was the Ypres salient,’ I said. Hudson asked for a cigarette. He must have been awake for some time. ‘Ypres,’ said Hudson as he lit the cigarette, ‘was that the site of a World War One battle?’

‘One of the biggest,’ I said. ‘There’s scarcely an Englishman that didn’t have a relative die here. Perhaps a piece of Britain died here too.’

Hudson looked out of the rear windows of the van. ‘It’s quite a place to die,’ he said.

32

Across the Ypres salient the dawn sky was black and getting lower and blacker like a Bulldog Drummond ceiling. It’s a grim region, like a vast ill-lit military depot that goes on for miles. Across country go the roads: narrow slabs of concrete not much wider than a garden path, and you have the feeling that to go off the edge is to go into bottomless mud. It’s easy to go around in circles and even easier to imagine that you are. Every few yards there are the beady-eyed green-and-white notices that point the way to military cemeteries where regiments of Blanco-white headstones parade. Death pervades the topsoil but untidy little farms go on operating, planting their cabbages right up to ‘Private of the West Riding – Known only to God’. The living cows and dead soldiers share the land and there are no quarrels. Now in the hedges evergreen plants were laden with tiny red berries as though the ground was sweating blood. I stopped the car. Ahead was Passchendaele, a gentle upward slope.

‘Which way were your soldiers facing?’ Kuang said.

‘Up the slope,’ I said. ‘They advanced up the slope, sixty pounds on their backs and machine guns down their throats.’

Kuang opened the window and threw his cigarette butt on to the road. There was an icy gust of wind.

‘It’s cold,’ said Kuang. ‘When the wind drops it will rain.’

Hudson leaned close to the window again. ‘Oh boy,’ he said, ‘trench warfare here,’ and shook his head when no word came. ‘For them it must have seemed like for ever.’

‘For a lot of them it was for ever,’ I said. ‘They are still here.’

‘In Hiroshima even more died,’ said Kuang.

‘I don’t measure death by numbers,’ I said.

‘Then it’s a pity you were so careful not to use your atom bomb on the Germans or Italians,’ said Kuang.

I started the motor again to get some heat in the car, but Kuang got out and stamped around on the concrete roadway. He did not seem to mind the cold wind and rain. He picked up a chunk of the shiny, clay-heavy soil peculiar to this region, studied it and then broke it up and threw it aimlessly across the field of cabbages.

‘Are we expecting to rendezvous with another car?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘You must have been very confident that I would come with you.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I was. It was logical.’

Kuang nodded. ‘Can I have another cigarette?’ I gave him one.

‘We’re early,’ complained Hudson. ‘That’s a sure way to attract attention.’

‘Hudson fancies his chances as a secret agent,’ I said to Kuang.

‘I don’t take to your sarcasm,’ said Hudson.

‘Well that’s real old-fashioned bad luck, Hudson,’ I said, ‘because you are stuck with it.’

Grey clouds rushed across the salient. Here and there old windmills – static in spite of the wind – stood across the skyline, like crosses waiting for someone to be nailed upon them. Over the hill came a car with its headlights on.

They were thirty minutes late. Two men in a Renault 16, a man and his son. They didn’t introduce themselves, in fact they didn’t seem keen to show their faces at all. The older man got out of the car and came across to me. He spat upon the road and cleared his throat.

‘You two get into the other car. The American stays in this one. Don’t speak to the boy.’ He smiled and gave a short, croaky, mirthless laugh. ‘In fact don’t speak to me even. There’s a large-scale map in the dashboard. Make sure that’s what you want.’ He gripped my arm as he said it. ‘The boy will take the camionette and dump it somewhere near the Dutch border. The American stays in this car. Someone will meet them at the other end. It’s all arranged.’

Hudson said to me, ‘Going with you is one thing, but taking off into the blue with this kid is another. I think I can find my own way …’

‘Don’t think about it,’ I told him. ‘We just follow the directions on the label. Hold your nose and swallow.’ Hudson nodded.

We got out of the car and the boy came across, slowly detouring around us as though his father had told him to keep his face averted. The Renault was nice and warm inside. I felt in the glove compartment and found not only a map but a pistol.

‘No prints,’ I called to the Fleming. ‘Make sure there’s nothing else, no sweet wrappers or handkerchiefs.’

‘Yes,’ said the man. ‘And none of those special cigarettes that are made specially for me in one of those exclusive shops in Jermyn Street.’ He smiled sarcastically. ‘He knows all that.’ His accent was so thick as to be almost unintelligible. I guessed that normally he spoke Flemish and the French was not natural to him. The man spat again in the roadway before climbing into the driver’s seat alongside us. ‘He’s a good boy,’ the man said. ‘He knows what to do.’ By the time he got the Renault started the camionette was out of sight.

I’d reached the worrying stage of the journey. ‘Did you take notes?’ I asked Kuang suddenly. He looked at me without answering. ‘Be sensible,’ I said. ‘I must know if you are carrying anything that would need to be destroyed. I know there’s the box of stuff Hudson gave you.’ I drummed upon it. ‘Is there anything else?’

‘A small notebook taped to my leg. It’s a thin book. I could be searched and they would not find it.’

I nodded. It was something more to worry about.

The car moved at high speed over the narrow concrete lanes. Soon we turned on to the wider main road that led north to Ostend. We had left the over-fertilized salient behind us. The fearful names: Tyne Cot, St Julien, Poelcapelle, Westerhoek and Pilckem faded behind us as they had faded from memory, for fifty years had passed and the women who had wept for the countless dead were also dead. Time and TV, frozen food and transistor radios had healed the wounds and filled the places that once seemed unfillable.

‘What’s happening?’ I said to the driver. He was the sort of man who had to be questioned or else he would offer no information.

‘His people,’ he jerked his head towards Kuang, ‘want him in Ostend. Twenty-three hundred hours tonight at the harbour. I’ll show you on the city plan.’

‘Harbour? What’s happening? Is he going aboard a boat tonight?’

‘They don’t tell me things like that,’ said the man. ‘I’m just conducting you to my place to see your case officer, then on to Ostend to see his case officer. It’s all so bloody boring. My wife thinks I get paid because it’s dangerous but I’m always telling her: I get paid because it’s so bloody boring. Tired?’ I nodded. ‘We’ll make good time, that’s one advantage, there’s not much traffic about at this time of morning. There’s not much commercial traffic if you avoid the inter-city routes.’

‘It’s quiet,’ I said. Now and again small flocks of birds darted across the sky, their eyes seeking food in the hard morning light, their bodies weakened by the cold night air.

‘Very few police,’ said the man, ‘The cars keep to the main roads. It will rain soon and the cyclists don’t move much when it’s raining. It’ll be the first rain for two weeks.’

‘Stop worrying,’ I said. ‘Your boy will be all right.’

‘He knows what to do,’ the man agreed.

33

The Fleming owned an hotel not far from Ostend. The car turned into a covered alley that led to a cobbled courtyard. A couple of hens squawked as we parked and a dog howled. ‘It’s difficult,’ said the man, ‘to do anything clandestine around here.’

He was a small broad man with a sallow skin that would always look dirty no matter what he did to it. The bridge of his nose was large and formed a straight line with his forehead, like the nose metal of a medieval helmet. His mouth was small and he held his lips tight to conceal his bad teeth. Around his mouth were scars of the sort that you get when thrown through a windscreen. He smiled to show me it was a joke rather than an apology, and the scars made a pattern around his mouth like a tightened hairnet.

The door from the side entrance of the hotel opened and a woman in a black dress and white apron stared at us.

‘They have come,’ said the man.

‘So I see,’ she said. ‘No luggage?’

‘No luggage,’ said the man. She seemed to need some explanation, as though we were a man and girl trying to book a double room.

‘They need to rest, ma jolie môme,’ said the man. She was no one’s pretty child, but the compliment appeased her for a moment.

‘Room four,’ she said.

‘The police have been?’

‘Yes,’ she said.

‘They won’t be back until night,’ said the man to us. ‘Perhaps not then even. They check the book. It’s for the taxes more than to find criminals.’

‘Don’t use all the hot water,’ said the woman. We followed her through the yellow peeling side door into the hotel entrance hall. There was a counter made of carelessly painted hardboard and a rack with eight keys hanging from it. The lino had the large square pattern that’s supposed to look like inlaid marble; it curled at the edges and something hot had indented a perfect circle near the door.

‘Name?’ said the woman grimly as though she was about to enter us in the register.

‘Don’t ask,’ said the man. ‘And they won’t ask our name.’ He smiled as though he had made a joke and looked anxiously at his wife, hoping that she would join in. She shrugged and reached behind her for the key. She put it down on the counter very gently so she could not be accused of anger.

‘They’ll need two keys, Sybil.’

She scowled at him. ‘They’ll pay for the rooms,’ he said.

‘We’ll pay,’ I said. Outside the rain began. It bombarded the window and rattled the door as though anxious to get in.

She slammed the second key down upon the counter. ‘You should have taken it and dumped it,’ said the woman angrily. ‘Rik could have driven these two back here.’

‘This is the important stage,’ said the man.

‘You lazy pig,’ said the woman. ‘If the alarm is out for the car and Rik gets stopped driving it, then we’ll see which is the important stage.’

The man didn’t answer, nor did he look at me. He picked up the keys and led the way up the creaky staircase. ‘Mind the handrail,’ he said. ‘It’s not fixed properly yet.’

‘Nothing is,’ called the woman after us. ‘The whole place is only half-built.’

He showed us into our rooms. They were cramped and rather sad, shining with yellow plastic and smelling of quick-drying paint. Through the wall I heard Kuang swish back the curtain, put his jacket on a hanger and hang it up. There was the sudden chug-chug of the water pipe as he filled the wash-basin. The man was still behind me, hanging on as if waiting for something. I put my finger to my eye and then pointed towards Kuang’s room; the man nodded. ‘I’ll have the car ready by twenty-two hundred hours. Ostend isn’t far from here.’

‘Good,’ I said. I hoped he would go but he stayed there.

‘We used to live in Ostend,’ he said. ‘My wife would like to go back there. There was life there. The country is too quiet for her.’ He fiddled with the broken bolt on the door. It had been painted over but not repaired. He held the pieces together, then let them swing apart.

I stared out of the window; it faced south-west, the way we had come. The rain continued and there were puddles in the roadway and the fields were muddy and windswept. Sudden gusts had knocked over the pots of flowers under the crucifix and the water running down the gutters was bright red with the soil it carried from somewhere out of sight.

‘I couldn’t let the boy bring you,’ the man said. ‘I’m conducting you. I couldn’t let someone else do that, not even family.’ He rubbed his face hard as if he hoped to stimulate his thought. ‘The other was less important to the success of the job. This part is vital.’ He looked out of the window. ‘We needed this rain,’ he said, anxious to have my agreement.

‘You did right,’ I said.

He nodded obsequiously, as if I’d given him a ten-pound tip, then smiled and backed towards the door. ‘I know I did,’ he said.

34

My case officer arrived about 11 A.M.; there were cooking smells. A large black Humber pulled into the courtyard and stopped. Byrd got out. ‘Wait,’ he said to the driver. Byrd was wearing a short Harris tweed overcoat and a matching cap. His boots were muddy and his trouser-bottoms tucked up to avoid being soiled. He clumped upstairs to my room, dismissing the Fleming with only a grunt.

‘You’re my case officer?’

‘That’s the ticket.’ He took off his cap and put it on the bed. His hair stood up in a point. He lit his pipe. ‘Damned good to see you,’ he said. His eyes were bright and his mouth firm, like a brush salesman sizing up a prospect.

‘You’ve been making a fool of me,’ I complained.

‘Come, come, trim your yards, old boy. No question of that. No question of that at all. Thought you did well actually. Loiseau said you put in quite a plea for me.’ He smiled again briefly, caught sight of himself in the mirror over the wash-basin and pushed his disarranged hair into place.

‘I told him you didn’t kill the girl, if that’s what you mean.’

‘Ah well.’ He looked embarrassed. ‘Damned nice of you.’ He took the pipe from his mouth and searched around his teeth with his tongue. ‘Damned nice, but to tell you the truth, old boy, I did.’

I must have looked surprised.

‘Shocking business of course, but she’d opened us right up. Every damned one of us. They got to her.’

‘With money?’

‘No, not money; a man.’ He put the pipe into the ashtray. ‘She was vulnerable to men. Jean-Paul had her eating out of his hand. That’s why they aren’t suited to this sort of work, bless them. Men were deceivers ever, eh? Gels get themselves involved, what? Still, who are we to complain about that, wouldn’t want them any other way myself.’

I didn’t speak, so Byrd went on.

‘At first the whole plan was to frame Kuang as some sort of oriental Jack-the-Ripper. To give us a chance to hold him, talk to him, sentence him if necessary. But the plans changed. Plans often do, that’s what gives us so much trouble, eh?’

‘Jean-Paul won’t give you any more trouble; he’s dead.’

‘So I hear.’

‘Did you arrange that too?’ I asked.

‘Come, come, don’t be bitter. Still, I know just how you feel. I muffed it, I’ll admit. I intended it to be quick and clean and painless, but it’s too late now to be sentimental or bitter.’

‘Bitter,’ I said. ‘If you really killed the girl, how come you got out of prison?’

‘Set-up job. French police. Gave me a chance to disappear, talk to the Belgians. Very co-operative. So they should be, with this damned boat these Chinese chappies have got anchored three miles out. Can’t touch them legally, you see. Pirate radio station; think what it could do if the balloon went up. Doesn’t bear thinking of.’

‘No. I see. What will happen?’

‘Government level now, old chap. Out of the hands of blokes like you and me.’

He went to the window and stared across the mud and cabbage stumps. White mist was rolling across the flat ground like a gas attack.

‘Look at that light,’ said Byrd. ‘Look at it. It’s positively ethereal and yet you could pick it up and rap it. Doesn’t it make you ache to pick up a paintbrush?’

‘No,’ I said.

‘Well it does me. First of all a painter is interested in form, that’s all they talk about at first. But everything is the light falling on it – no light and there’s no form, as I’m always saying; light’s the only thing a painter should worry about. All the great painters knew that: Francesca, El Greco, Van Gogh.’ He stopped looking at the mist and turned back towards me glowing with pleasure. ‘Or Turner. Turner most of all, take Turner any day …’ He stopped talking but he didn’t stop looking at me. I asked him no question but he heard it just the same. ‘Painting is my life,’ he said. ‘I’d do anything just to have enough money to go on painting. It consumes me. Perhaps you wouldn’t understand what art can do to a person.’

‘I think I’m just beginning to,’ I said.

Byrd stared me out. ‘Glad to hear it, old boy.’ He took a brown envelope out of his case and put it on the table.

‘You want me to take Kuang up to the ship?’

‘Yes, stick to the plan. Kuang is here and we’d like him out on the boat. Datt will try to get on the boat, we’d like him here, but that’s less important. Get Kuang to Ostend. Rendezvous with his case chappie – Major Chan – hand him over.’

‘And the girl, Maria?’

‘Datt’s daughter – illegitimate – divided loyalties. Obsessed about these films of her and Jean-Paul. Do anything to get them back. Datt will use that factor, mark my words. He’ll use her to transport the rest of his stuff.’ He ripped open the brown envelope.

‘And you’ll try to stop her?’

‘Not me, old boy. Not my part of the ship those dossiers, not yours either. Kuang to Ostend, forget everything else. Kuang out to the ship, then we’ll give you a spot of leave.’ He counted out some Belgian money and gave me a Belgian press card, an identity card, a letter of credit and two phone numbers to ring in case of trouble. ‘Sign here,’ he said. I signed the receipts.

‘Loiseau’s pigeon, those dossiers,’ he said. ‘Leave all that to him. Good fellow, Loiseau.’

Byrd kept moving like a flyweight in the first round. He picked up the receipts, blew on them and waved them to dry the ink.

‘You used me, Byrd,’ I said. ‘You sent Hudson to me, complete with prefabricated hard-luck story. You didn’t care about blowing a hole in me as long as the overall plan was okay.’

‘London decided,’ Byrd corrected me gently.

‘All eight million of ’em?’

‘Our department heads,’ he said patiently. ‘I personally opposed it.’

‘All over the world people are personally opposing things they think are bad, but they do them anyway because a corporate decision can take the blame.’

Byrd had half turned towards the window to see the mist.

I said, ‘The Nuremberg trials were held to decide that whether you work for Coca-Cola, Murder Inc. or the Wehrmacht General Staff, you remain responsible for your own actions.’

‘I must have missed that part of the Nuremberg trials,’ said Byrd unconcernedly. He put the receipts away in his wallet, picked up his hat and pipe and walked past me towards the door.

‘Well let me jog your memory,’ I said as he came level and I grabbed at his chest and tapped him gently with my right. It didn’t hurt him but it spoiled his dignity and he backed away from me, smoothing his coat and pulling at the knot of his tie which had disappeared under his shirt collar.