По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

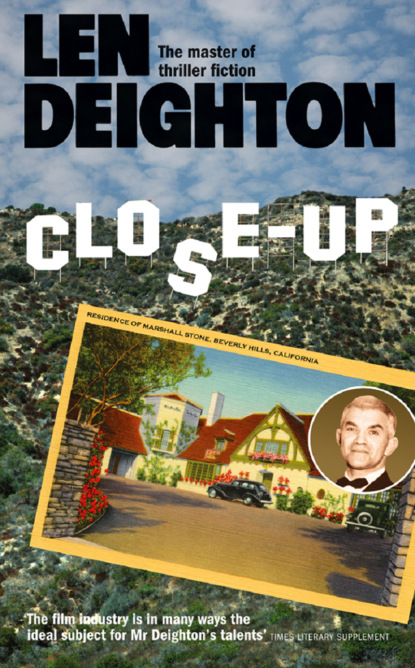

Close-Up

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Edgar Nicolson Productions for Koolman International presents

Stool Pigeon starring Marshall Stone

Director: Richard Preston

Introducing: Suzy Delft.

MARSHALL STONE. A brief biography.

Marshall Stone was born in London. In a family that traditionally supplied its sons to the theatre and to the Army, Stone’s dilemma as an only child was resolved when war interrupted his studies at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

After the war he auditioned for Robert Atkins at Stratford and was so disappointed at being turned down that he toured South Africa with a company that did light comedy with music in its repertory, as well as a detective play and a farce. ‘It was a lunatic asylum,’ said Stone afterwards, ‘but we never stopped laughing in spite of the miseries and the hard work of it all.’ When he returned to England he joined the Birmingham Rep. His performance as Fortinbras in Hamlet was singled out for critical praise but apart from this his season went unmarked. ‘I spent my whole time there in open-mouthed awe. Perhaps I took direction too slavishly, for I never recognized anything of myself in the roles I played.

‘After getting into Birmingham – which had long been my ambition – I believed that the world was at my feet. I was wrong. After Birmingham I was turned down for three London parts. For a year I took anything I could get, including some TV work.’

In 1948 he was offered Lysander in a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that was to be staged in New York. They were actually in rehearsals when a network cutback caused the whole production to be scrapped. He stayed in New York and got a small part in an experimental group’s production of Brecht and eked out his finances with odd jobs on TV. He was in a restaurant in New York when he was seen by a Hollywood producer who screen-tested him for Last Vaquero, the film that brought him world-wide acclaim and broke box-office records in many countries from Japan to Italy.

In the following two years he starred in three Hollywood films, as well as creating his memorable Master Builder on the London stage and the exciting Tristram Shandy, Gent that was written for him to do at the Edinburgh Festival. No theatrical event of the nineteen-fifties was more important than Marshall Stone’s Hamlet. Gielgud himself called it ‘a miracle of discovery’.

Since that time Marshall Stone has divided his work between the stage and screen, as well as financing some avant-garde productions in Paris and doing a series of poetry readings for the BBC Third programme.

If there is one certain thing about the career of Marshall Stone, it is that no one can be certain what he will do next, except that it will be important, highly professional and never, never boring.

It was a good piece of publicity. But for those of us in never-never-boring-land who had learned to interpret avant-garde as disastrous, and exciting as unrehearsed, it left only the radio poetry, an assorted collection of forgettable films, Hamlet and The Master Builder.

The fact that the Ibsen performance had been superb and his Hamlet even better made the whole thing more, not less, depressing for me.

Listed under the biography were his films. Last Vaquero was at the top, but the compilation had omitted some of his worst flops including Tigertrap which, after its panning in New York, had been shelved until this week.

Even so, the achievements of Stone were remarkable and it would be a foolish historian who wrote of the postwar theatre without acknowledging his contribution. That he’d neglected the stage since Hamlet and contented himself with countless disappointing films didn’t obscure the dazzling talent that could be discerned in every performance he gave. As Scofield followed in the steps of Gielgud, so could Stone have followed Olivier. It still wasn’t too late; it was simply very unlikely.

In the same envelope there was the call-sheet for Stool Pigeon. The unit was on location outside Wellington Barracks.

Dear Peter Anson,

For the next three days Mr Marshall Stone will be working at Tiktok Sound Recording Studios in Wardour Street. He will be pleased to see you at any time you care to drop in.

Yours sincerely,

BRENDA STAPLES,

Publicity Secretary

No wonder schizophrenia was an occupational hazard among actors. At any time an actor might be doing publicity for a film that was being premièred, recording for one in post-production, acting in a third, fitting costumes for a fourth while reading scripts to decide what will come next.

In the competitive spirit of all flacks the note didn’t say which film Stone was looping, but I guessed it was one about the Alaskan oil pipeline that had been recut half a dozen times due to arguments between Nicolson, the director and some of Koolman’s people.

I saw Stone’s Rolls outside Tiktok, parked with the impunity that only chauffeurs manage. Its dark glass concealed the interior, which made one wonder why Stone had gone to the trouble of getting a registration plate that contained his initials.

Usually the door of Tiktok was ajar but today it was locked, with a suspicious guardian who grudgingly permitted me inside. Only fifty yards of corridor separated Studio D from the door but I passed through a screen of secretaries, bodyguards, tea-bringers, overcoat holders, messengers, advisers and a bald man whose sole job it was to pay for refreshments for the whole ensemble and note each item in his tiny notebook. Even the man who answered the phone that Stone had commandeered was not the one who made calls on Stone’s behalf.

They were a curious assembly of shapes, sizes and ages, dressed as variously as a random crowd in a bus queue. Their only bond was the fealty they demonstrated to Stone, for homage must not only be paid but also be seen to be paid. In common they had the same expression of bored indifference that all servants hide behind. They used it to admit me and to reply to my ‘good mornings’. They would use it to take my coat and bring me coffee and politely acknowledge any joke I cared to make. And, if necessary, they would use it when they tossed me out of the door or repeated for the umpteenth time that Stone was not at home.

Stone had hired them under many different circumstances, and in some cases their employment was little more than an excuse for Stone’s charity. Valuable though they were as retainers, they were even more vital as an audience. They travelled with Stone providing the affection, scandals, jokes, flattery and feuds – arbitrated by Stone – that an Italian padrone exacted from his family. This was the world of Stone and, like the world which he portrayed on the screen, it was contrived.

When I finally penetrated Studio D, Marshall Stone was sitting in an Eames armchair alongside an antique occasional table, on which was set coffee and cakes with Copenhagen china and silver pots. Later I was to hear that the chair and all the trimmings were brought there in advance by his employees, whose job it was to scout all such places and furnish them tastefully.

I recognized Sam Parnell and his usual assistants. They were sitting in a glass booth surrounded by the controls of the recording equipment. They were drinking machine-made coffee from paper cups. The booth was lighted by three spotlights over the swivel chairs. Enough light spilled from them to see the six rows of cinema seats and Stone sitting at the front. Parnell’s voice came over the loudspeaker as I entered. ‘OK, Marshall. Ready when you are.’

Stone gave him the thumbs-up sign and handed his copy of Playboy to a man who would hold it open at the right place until it was needed again. On the screen of the dimmed room there appeared a scratched piece of film. It was a black and white dupe print of Silent Paradise. Carelessly processed, its definition was fuzzy and the highlights burned out. A blobby man in glaring white furs said, ‘It should be me that goes, the other men have wives and families. I have no one.’

Marshall Stone watched himself and listened to the guide tracks so that as the loop of picture came round again he could record the words in synchronization with his lips. The trouble with looping was that men on the tundra were likely to sound as if they had their heads inside biscuit tins. This film was not going to be an exception. Edgar Nicolson productions seldom were.

The picture began again, Stone said, ‘It should be me that goes, the other – no, sod. Sorry, boys, we’ll have to do it again.’ The screen flashed white, and by its reflected light Stone saw me standing in the doorway. Although one of his servants had announced my arrival he preferred to act as though it was a chance meeting.

We had exchanged banalities at parties and he’d given me a brief interview for the newspaper articles, but this was a meeting between virtual strangers. That however was not evident from the warmth of his welcome.

He came towards me smiling broadly as he took my hands in his. He delivered a salvo of one-word sentences, ‘Wonderful. Marvellous. Great. Super.’ Narrow-eyed, he watched the effect of them like an artillery observer. Then he adjusted the range and the fuse setting to hit instead of straddling. ‘Damned fit. And a superb suit. Where did you get that wonderful tan: I’m jealous.’ Perhaps because he told me the things he wanted to tell himself there was an artless sincerity in his voice.

‘You’re looking well yourself, Marshall,’ I responded. He gripped my hand. He was smaller, more wrinkled and more tanned than I remembered, but his voice had the same tough reedy tone that I’d heard in his films.

‘Are you having problems?’ I asked.

‘It’s the stutter, darling.’ He could say ‘darling’ with such virile aplomb that it became the most sincere and effective greeting that one man could use to another.

‘I see.’

‘I would never have used a hesitation if I’d guessed I’d be looping it.’ The joke was on him but he laughed.

‘The sound crew thought they could use the original track?’

‘They swore that they’d be able to, but I could hear the genny and so could everyone else. If we could hear it, then the mike could pick it up. I should have put my foot down. God knows, I’ve been in the business long enough to know about recordings. But a bloody actor must know his place, eh, Peter?’ He pulled a slightly anguished face – hollow cheeks and half-closed eyes – before letting it soften into a broad smile. Just as his speech was articulated with an actor’s care, so did all his gestures have a beginning, middle and an end. He shook his head to remove the smile. ‘Get Mr Anson a fresh pot of coffee and some of those flaky pastries, will you, Johnny.’

Another man helped me off with my coat. I said, ‘The publicity secretary said…’

‘Sure, Peter, she said you might look in. Sandy, take Peter’s coat.’ Yet a third man put my coat on a hanger and carried it away with either reverence or disgust, I could not be sure which. ‘Glad of someone to talk to,’ said Stone. ‘Bloody boring, doing these loops. Will it be a full-length book?’

‘Yes. About eighty thousand words and lots of photos. By the way, the publicity people will let me have plenty of film stills but I was wondering if you have any personal snapshots you could lend me. You know: school groups, holiday snaps, mother, father or wartime photos.’ He looked up and stared at me.

‘I was in the war,’ he said.

‘What did you do?’

He stared at me until I shifted uncomfortably. ‘What did you do in the war, Daddy?’

I laughed nervously. ‘You know what I did, Marshall. I sat on my arse in Hollywood.’

He sensed my discomfort. ‘Yes, I know. Why?’