По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

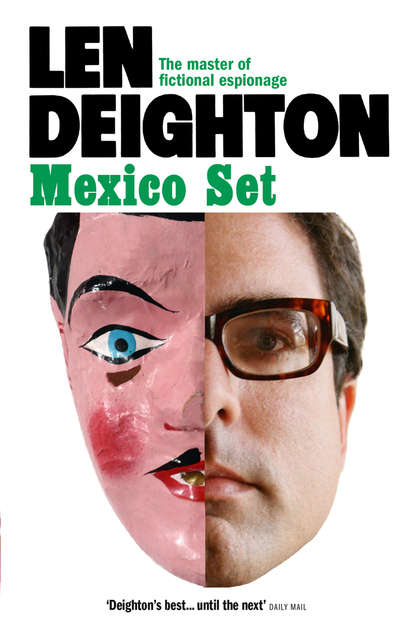

Mexico Set

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘She’s very young, Werner.’

‘Too young for me, you mean?’

I worded my answer carefully. ‘Too young to know what the real world is like, Werner.’

‘Yes, poor Zena.’

‘Yes, poor Zena,’ I said. Werner looked at me to see if I was being sarcastic. I smiled.

‘This is a beautiful hotel,’ said Werner. We were sitting on the balcony having breakfast. It was still early in the morning, and the air was cool. The town was behind us, and we were looking across gently rolling green hills that disappeared into gauzy curtains of morning mist. It could have been England; except for the sound of the insects, the heavy scent of the tropical flowers, and the vultures that endlessly circled high in the clear blue sky.

‘Dicky found it,’ I said.

Zena had let Werner off his lead for the day, and he’d come to Cuernavaca – a short drive from Mexico City – to tell me about his encounter with Stinnes at the Kronprinz Club. Dicky had decided to ‘make our headquarters’ in this sprawling resort town where so many Americans came to spend their old age and their cheap pesos. ‘Where’s Dicky now?’ said Werner.

‘He’s at a meeting,’ I said.

Werner nodded. ‘You’re smart to stay here in Cuernavaca. This side of the mountains it’s always cooler and you don’t have to breathe that smog all day and all night.’

‘On the other hand,’ I said, ‘I do have Dicky next door.’

‘Dicky’s all right,’ said Werner. ‘But you make him nervous.’

‘I make him nervous?’ I said incredulously.

‘It must be difficult for him,’ said Werner. ‘You know the German Desk better than he’ll ever know it.’

‘But he got it,’ I said.

‘So did you expect him to turn a job like that down?’ said Werner. ‘You should give him a break, Bernie.’

‘Dicky does all right,’ I said. ‘He doesn’t need any help. Not from you, not from me. Dicky is having a lovely time.’

Dicky had lined up meetings with a retired American CIA executive named Miller and an Englishman who claimed to have great influence with the Mexican security service. In fact, of course, Dicky was just trying out some of the best local restaurants at the taxpayer’s expense, while extending his wide circle of friends and acquaintances. Dicky had once shown me his card-index files of contacts throughout the world. It was quite unofficial, of course; Dicky kept them in his desk at home. He noted the names of their wives and their children and what restaurants they preferred and what sort of house they lived in. On the other side of each card Dicky wrote a short résumé of what he estimated to be their wealth, power and influence. He joked about his file cards; ‘he’ll be a lovely card for me,’ he’d say, when someone influential crossed his path. Sometimes I wondered if there was a card there with my name on it and, if so, what he’d written on it.

Dicky was a keen traveller, and his choice of bars, restaurants and hotels was the result of intensive research through guidebooks and travel magazines. The Hacienda Margarita, an old ranchhouse on the outskirts of town, was proof of the benefits that could come from such dedicated research. It was a charming old hotel, its cool stone colonnades surrounding a courtyard with palmettos and pepper trees and tall palms. The high-ceilinged bedrooms were lined with wonderful old tiles, and there were big windows and cool balconies, for this place was built long before air-conditioning was ever contemplated, built at the time of the conquistadores if you could bring yourself to believe the plaque over the cashier’s desk.

Meanwhile I was enjoying the sort of breakfast that Dicky insisted was the only healthy way to start the day. There was a jug of freshly pressed orange juice, a vacuum flask of hot coffee, canned milk – Dicky didn’t trust Mexican milk – freshly baked rolls and a pot of local honey. The tray was decorated with an orchid and held a copy of The News, the local English-language newspaper. Werner drank orange juice and coffee but declined the rolls and honey. ‘I promised Zena that I’d lose weight.’

‘Then I’ll have yours,’ I said.

‘You’re overweight too,’ said Werner.

‘But I didn’t make any promises to Zena,’ I said, digging into the honey.

‘He was there last night,’ said Werner.

‘Did he go for it, Werner? Did Stinnes go for it?’

‘How can you tell with a man like Stinnes?’ said Werner. ‘I told him that I’d met a man here in Mexico whom I’d known in Berlin. I said he had provided East German refugees with all the necessary papers to go and live in England. Stinnes said did I mean genuine papers or false papers. I said genuine papers, passports and identity papers, and permission to reside in London or one of the big towns.’

‘The British don’t have any sort of identity papers,’ I said. ‘And they don’t have to get anyone’s permission to go and live in any town they like.’

‘Well, I don’t know things like that,’ said Werner huffily. ‘I’ve never lived in England, have I? If the English don’t need papers, what the hell are we offering him?’

‘Never mind all that, Werner. What did Stinnes say?’

‘He said that refugees were never happy. He’d known a lot of exiles and they’d always regretted leaving their homeland. He said they never properly mastered the language, and never integrated with the local people. Worst of all, he said, their children grew up in the new country and treated their parents like strangers. He was playing for time, of course.’

‘Has he got children?’

‘A grown-up son.’

‘He knew what you were getting at?’

‘Perhaps he wasn’t sure at first, but I persisted and Zena helped. I know she said she wouldn’t help, Bernie, but she did help.’

‘What did she do?’

‘She told him that a little money solves all kinds of problems. Zena said that friends of hers had gone to live in England and loved every minute of it. She told him that everyone likes living in England. These friends of hers had a big house in Hampshire with a huge garden. And they had a language teacher to help them with their English. She told him that these were all problems that could be solved if there was help and money available.’

‘He must have been getting the message by that time,’ I said.

‘Yes, he became cautious,’ said Werner. ‘I suppose he was frightened in case I was trying to make a fool of him.’

‘And?’

‘I had to make it a little more specific. I said that this friend of mine could always arrange a job in England for anyone with experience of security work. He’d just come down here for a couple of weeks’ holiday in Mexico after travelling through the US, recruiting security experts for a very big British corporation, a company that did work for the British government. The pay is very good, I told him, with a long contract optional both sides.’

‘I wish you really did have a friend like that, Werner,’ I said. ‘I’d want to meet him myself. How did Stinnes react?’

‘What’s he going to say, Bernie? I mean, what would you or I say, in his place, faced with the same proposition?’

‘He said maybe?’

‘He said yes … or as near as he dared go to yes. But he’s frightened it’s a trap. Anyone would be frightened of it being a trap. He said he wanted more details, and a chance to think about it. He’d have to meet the man doing the recruiting. I said I was just a go-between of course …’

‘And he believed you are just the go-between?’

‘I suppose so,’ said Werner. He picked up the orchid and examined it as if seeing one for the first time. ‘You can’t grow orchids in Mexico City, but here in Cuernavaca they flourish. No one knows why. Maybe it’s the smog.’

‘Don’t just suppose so, Werner.’ He made me angry when he avoided important questions by changing the subject of conversation. ‘I wasn’t kidding last night … what I said to Zena. I wasn’t kidding about them getting rough.’

‘He believed me,’ said Werner in a tone that indicated that he was just trying to calm me down.

‘Stinnes is no amateur,’ I said. ‘He’s the one they assigned to me when I was arrested over there. He had me taken to the Normannenstrasse building and sat with me half the night, discussing the more subtle aspects of Sherlock Holmes and laughing and smoking and making it clear that if he was in charge of things they’d be kicking shit out of me.’

‘We’ve both seen a lot of KGB specimens like Erich Stinnes,’ said Werner. ‘He’s affable enough over a stein of beer but in other circumstances he could be a nasty piece of work. And not to be trusted, Bernie. I kept my distance from him. I’m no hero, you know that.’