По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

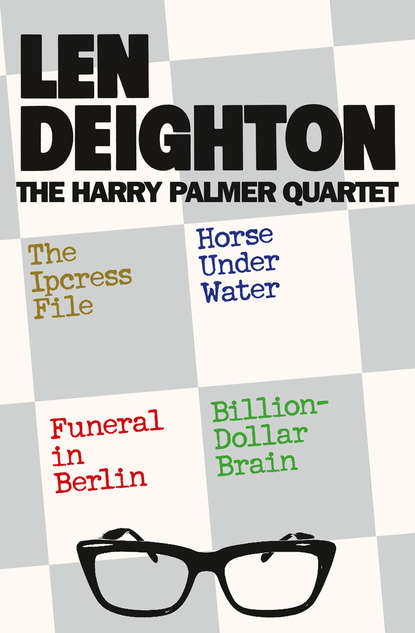

The Harry Palmer Quartet

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘If I wait any longer for this steak,’ Dalby joined the conversation.

‘Hey there, welcome back to the human race,’ I said. ‘I thought we’d left you way back there taking orders from Lt-General Skip Henderson.’

‘The next table but one has emptied and filled up twice while we’ve been sitting here drinking this terrible gin that’s probably distilled by some avaricious procurement corporal in one of the battery huts.’

‘Stop getting excited,’ Jean said. When off duty, she had a knack of reverting to a domineering feminine role in life without being noticeably insubordinate. ‘You know there’s just nothing you would be doing if we’d finished dining except arguing with the waiter that the brandy isn’t what you’re used to back at the castle.’

‘I’ll be dashed if I’ve ever encountered a more mordant pair.’

‘You can’t say “dashed” in an Hawaiian shirt,’ I said to Dalby.

‘Most especially not out of the side of a mouth ninety per cent occupied by a twenty-five-cent black cheroot,’ said Jean.

‘But since the waiter is having trouble getting the cows to stand still I’ll dive across for a word with Barney – about stats.’

‘You just sit still where you are. Social life can come to a standstill till I’ve eaten.’ I knew Dalby by now, and I could recognize moods in his voice. He wasn’t kidding and he hadn’t enjoyed us fooling with him. To make Dalby happy you had to listen to and commiserate with him, just every little thing that marred his day and then make with the feet to rectify things. By Dalby’s understanding of life I should be standing in the kitchen now making sure that only the finest fermented wine vinegar went into his salad-dressing. It doesn’t take much to make the daily round with one’s employer work smoothly. A couple of ‘yessirs’ when you know that ‘not on your life’ is the thing to say. A few expressions of doubt about things you’ve spent your life perfecting. Forgetting to make use of the information that negates his hastily formed but deliciously convenient theories. It doesn’t take much but it takes about 98.5 per cent more than I’ve ever considered giving.

‘Be back in a minute,’ I said, and edged past a red-faced colonel who was saying to a waiter, ‘You just tell your officer that this young lady here says that none of these Camembert cheeses are ripe, she knows what she’s talking about. Yes, sir, and just as long as I’m paying the bill around here I just don’t intend to have any more arguments …’

I didn’t look back at Dalby but I imagined that Jean was trying to placate him in some way.

A long bar filled one end of the restaurant. The lighting was low and arranged to shimmer translucently through the bottles of drink that stood back to back with their reflections across the mirror wall. At the far end, the ‘Parisian décor’ was completed with the largest size in Espresso machines, which stood silent with the message ‘No Steam’ glowing blue from its navel. Behind the bar, spaces between the bottles were found for wooden slats with decorative serrated edges that held prefabricated jokes in Saxon lettering. Under one: ‘Spit on the ceiling. Any fool can spit on the floor’ stood a little knot of flyers in uniform. I moved slowly through them. A young sun-bronzed pilot was doing a trick on the counter that involved a glass of water and fifty matches. My guess was that the pay-off was likely to be the distribution of the water and matches among his not altogether unsuspecting colleagues. I moved a little faster. Barney was lighting a cigarette for the blonde now. I walked across the handkerchief-sized dance floor. The enormous juke-box glowed like a monkey’s bottom, and the opening bars of a cha cha cha rent the smoke. A fat man in bright Hawaiian shirt lumbered laughingly towards me, his fists shadow boxing in time to the music, the perspiration sitting heavily across his face. I negotiated the floor ducking and weaving. At closer quarters one could see how much older Barney had got since I last saw him. His crew-cut was a little frayed on top.

Barney saw me across the floor and gave me the big-smile treatment. He spoke suddenly and quickly to the blonde who nodded. I smiled inside as I thought I detected another little Barney ‘If-anybody-asks-you’re-my-assistant-and-we’ve-been working-till-late-and-we-are-finishing-the-last-details-now’ sort of conversation.

I was sufficiently English to find it difficult to say nice things to people I really liked, and I really liked Barney.

Barney’s blonde leaned forward, face close against the table-cloth as she ran a forefinger round the heel of her shoe to ease it on. She was losing a hair grip from the ocean of hair drawn tight against her neck. Barney looked anxiously into my face.

‘Pale-face I love,’ Barney said.

‘Red man, him speak with forked tongue.’

‘So what’s the good word, kid?’ His rich bluey-brown face was lit by a smile. His crisp uniform shirt carried the insignia of a lieutenant of Engineers, and a plastic-faced white card showing two photographs of him and a large pink letter ‘Q’ hung from the button on the pocket of his shirt. According to this card he was Lieutenant Lee Montgomery, and I could make out the word ‘Power’ against unit. Barney had come to his feet now and I felt dwarfed by his bulk.

‘Just through eating, man.’ He fed a dollar bill under the ashtray. ‘Must be stepping, just about shot with these early morning, late night routines.’

The waiter was helping the blonde back into her silk coat. Barney fidgeted his way around the table tightening his tie, and rubbing the palms of his hands against his hips.

‘I saw an old friend of yours the other day from Canada. We were talking about how much dough we spent in that bar in King Street, Toronto. He was reminding me about that song you always sang when you were plastered.’

‘Nat?’ I said.

‘That’s him,’ agreed Barney. ‘Nat Goodrich. What’s that old song you were always singing, how’d the words go now? Shoot, I know. “Be first to climb the mountain and climb it alone”.’

I said, ‘I sure do, I sure do,’ a couple of times, and Barney was rattling on in a cheerful sort of way, ‘Maybe we’ll do a night out sometime real soon. What were those things you were drinking in that bar next door to the Embassy that time? Remember those vodka benedictine concoctions that you christened E-mc2? Oooh man, but lethal. But can’t do the night out, pal, for a little while. I’m shipping out in a day or so. Must go.’

His blonde had been standing listening in a bored sort of way, but now she was getting impatient eyes. I put it down to a hunger. A sudden belt of laughter fanned from the bar. I guessed that one of those transport pilots had collected the glassful of water. It was the only correct guess I made that puzzling day, for about the only thing less likely than me drinking a mixture of benedictine and vodka was me singing. And I’d never been in Toronto with Barney, I knew no one named Nat, and I don’t suppose Barney knew anyone named Goodrich.

(#ulink_32b1615f-7b5f-5b3c-bd3f-c25a1f5ec61c) See Appendix: Joe One (#ulink_689362cc-d64f-5629-b638-fb62e4eae3c5)

(#ulink_7936d42e-47fe-5b8e-a612-472ae768f048) Approximately 2,500 times the destructive power of the Hiroshima explosion.

(#ulink_f57e3945-3ab2-5c67-833a-2f2d1f2aa862) For details see Appendix (#litres_trial_promo)

19 (#ulink_ff5a1d68-defa-5dc1-9f66-1257cd86db35)

[Aquarius (Jan 20–Feb 19) People you work with seem to misunderstand your intentions, but don’t brood – look on the cheerful side.]

The heat rocketed back from the burning sand underfoot. The red painted framework of girders that made the shot tower blistered the careless hand. Wriggling away from the legs of the tower, black smooth cables and corrugated pipelines rested along each other like a Chinese apothecary’s box of snakes. Fifty yards away a twenty-foot-high electric fence, circumscribing the tower, was manned by white-helmeted police with panting Alsatian dogs on short leashes. A white amphibious jeep was parked near the only gate, its awning modified to permit the traverse of a half-inch-calibre machine-gun. The driver sat with hands clasped high on the steering-column, his chin resting on the back of his thumb. His helmet liner was painted in lateral black and yellow two-inch stripes to show he had a ‘Q’ permit. He looked like Danny Kaye.

Half a mile away across the flat sand I could see small shimmering black figures adjusting the automatic cameras which at this range could only be preserved by a freak of failure. With a well-oiled sound a three-man lift dropped down the tower with the accuracy of a guillotine blade and bobbed gently on its spring cushion. My guide was a small lizard-like civilian with hard, horny hands and face, and the lightest blue eyes I ever saw. His white shirt had small darns such as only a loving wife can do, and only a tight salary bracket make necessary. Across the back of one hand was a faded tattoo, an anchor design from which a name had been erased. The plain gold signet-ring caught the sun through his copious white hair.

‘I’ve got a meter here with mercury in it.’ I tapped the old leather brief-case. ‘It had better not go near the cold box.’ I looked up to where the pipes got thicker and more numerous two or three platforms up. I pointed vaguely. ‘The refrigeration chamber might react.’ I looked up again, and he looked at my badge and read the words, ‘Vickers Armstrong Engineering’. He nodded without much emotion.

‘Don’t let anybody touch it.’ He nodded again as I opened the wire gate of the lift and stepped in. I pulled the little handle and we stood motionless, looking at each other as the motor whirled away its inertia. ‘Down in a minute,’ I said, rather than just stand there dumbly. He nodded his white head slowly and deliberately, as one would to a sub-intelligent child or foreigner, and the lift surged upward. The red girders cut the white hot sand into Mondrian-like shapes moving before me more quickly as the lift gained speed. The wire roof divided the dark-blue sky into a hundred rectangles as the oily steel lift cable passed me on its journey downward. No sooner did the platforms permit me to peek over them than they fell away beneath my feet. For 200 feet I rocketed into the air, the circle of fencing falling around my feet like a spent hula hoop. Through the crack in the floorboard I watched the white police jeep lazily trot round the tower, on the sand that the explosion would transform into glass.

Suddenly the motor cut out and there I hung bouncing in space like a budgerigar in a sprung cage. I slid the gate aside and stepped out on to the top platform. I could see right across the island. To the south the sharp runways of Lay Field contrasted strangely with the irregular patterns of nature all around. A B52 was taking off from the field. Its heavy fuel for the long transpacific journey challenging it to defy gravity. Other smaller, rockier islands played bob-apple in the ocean waves. Beneath my feet the complexities of machinery reached their most frenetic maze. I was standing atop the thing that all this was about, this atoll, this multi-million-dollar city, this apogee of twentieth-century achievement, this focus point of hemispherical animosity, this reason why a Leeds supermarket operator can’t afford a third car, and a farmer in Szechwan a third bowl of rice.

Because it was all these things the shot tower was generally called ‘the mountain’, and because it was called that I wasn’t surprised to find Barney waiting at the summit.

Barney was dressed in white, super-lightweight coveralls. On his arm were the stripes of a master-sergeant, in his hand a .32 pistol with silencer. It just happened to be pointing at me.

‘I’d just better be right about you, pale-face,’ he said.

‘You’d just better had, Sambo. Now ease down the drama and tell me what’s on your mind.’

‘You are.’

‘You’re nice.’

‘Don’t fool, because I’m sticking my neck right out, but I can rack it in, but very fast. We knew each other well once, but people change and I just need to look, to see. Have you changed?’

‘Probably I have.’

There was a long silence. I didn’t know what Barney was talking about, or what Barney was getting at. I was almost thinking out loud when I said, ‘One morning you wake up and find all your life-long friends changed. They had turned into the sort of people you mutually despised not so long ago. Then you start worrying about yourself.’

‘Yeah,’ said Barney. ‘And they’ve stopped being interested in doing anything about those same jerks.’

‘I’m interested.’

‘That’s ’cos you don’t know when you’re licked.’

‘Maybe it is. But I don’t lure people into the barrel of a police special to prove it.’ He didn’t smile. Maybe I hadn’t made a joke.

He said, ‘So I’ve changed, so I’m a nut. Listen, white man, do you know the hottest piece of merchandise on this island …’

‘Aren’t I standing on it?’ I said.