По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

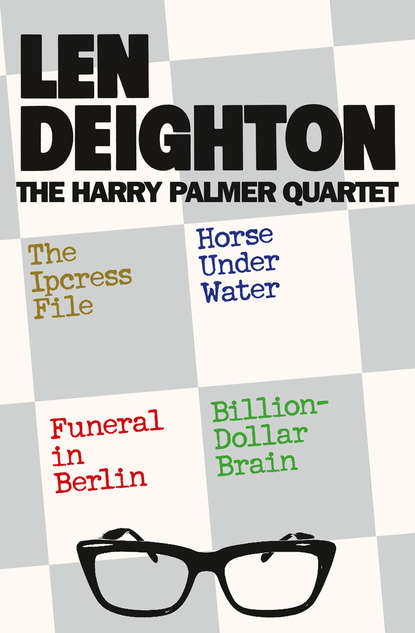

The Harry Palmer Quartet

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Gilbert White, 1778

Contents

Cover (#u39897bf4-551d-5bc8-8c41-a0a858afe423)

Cover Designer’s Note (#u835b7dcb-3943-59fd-b377-13a1068fba42)

Title Page (#u60bf3c4a-f6bf-5c9d-9526-e94f4e4b13c2)

Epigraph (#u392756b7-ef43-5bab-87df-8860187d8257)

Introduction (#u89e3f141-59c5-5637-a00c-8796ec7c2cec)

Prologue (#u35a57f59-71f1-56e2-8d0e-5d51781c9d34)

Chapter 1 (#u50d1a0ff-bde3-5db6-bee9-1442cbaf5183)

Chapter 2 (#u3c1ba61e-a312-59be-8c23-c9dce16ce885)

Chapter 3 (#u12a23870-4b0b-5940-adaf-200bd6103de5)

Chapter 4 (#u0fac6ab9-d38f-50ef-9d4a-24cb02d41b64)

Chapter 5 (#ua9053825-e3fa-5262-9533-aa244f77b25b)

Chapter 6 (#uf36a8daa-e689-5424-9d11-11cbd784571f)

Chapter 7 (#u7392c995-f7f4-5f57-a39d-b24342753a5d)

Chapter 8 (#ub5575fbb-386d-5ffe-b2d5-ed837ce62bff)

Chapter 9 (#u27fffa6e-901d-5784-a6ac-69bb4fda31e4)

Chapter 10 (#u6a9a3bec-fb79-561a-9f9d-9a86fb3a5d1b)

Chapter 11 (#u437bd682-3101-54f8-8670-8267d559654a)

Chapter 12 (#u881202ed-d29f-5704-8772-f5d3d3a5b2cc)

Chapter 13 (#u9d5bce24-eb4a-5a5d-9db0-97d4c45e7c67)

Chapter 14 (#u02c14cf2-7e57-5c9a-b93d-9bb8731394ff)

Chapter 15 (#u180d68ad-4f4d-58dd-b63e-70d505406417)

Chapter 16 (#ude2f4324-76bd-589c-ba3c-24fcbfc32e97)

Chapter 17 (#ud5f132af-0818-5269-ba46-899cf7e4d05f)

Chapter 18 (#ue97e1bec-9892-5720-8c57-68a6fbbb1c3b)

Chapter 19 (#u6f226afb-62ba-5a97-b41b-7ffc22414446)

Chapter 20 (#uf5276ec3-4eac-5e81-af39-bf839cf52710)

Chapter 21 (#uccdfe280-8557-5a26-9458-e4f4b102059a)

Chapter 22 (#u185e3331-c80f-5a8a-862b-228cf213c729)

Chapter 23 (#u9354ff3e-7d37-5a8d-9e7f-4fad780be72c)

Chapter 24 (#ubb905596-0d25-540c-8a05-9c0959589150)

Chapter 25 (#u431d4df8-0185-524e-be32-24e7b5d5e70d)

Chapter 26 (#ua48f5e16-b56d-5952-ad77-8b473aa5dcc7)

Chapter 27 (#u088bca97-3793-5112-a6f0-e1ad13a8b1a1)

Chapter 28 (#uae9add6d-b9ce-50e6-a4a3-1294551c8d98)

Chapter 29 (#u2d21ed89-d957-558b-a273-16684b2e1082)

Chapter 30 (#u6dd58f3c-435c-575b-ac25-75d7247c93e8)

Chapter 31 (#u180d60a1-c486-5da7-8e49-575568aa76d5)

Chapter 32 (#ue0ce9f0a-4911-53ff-a090-6d2b5027ca11)

Epilogue (#u676e574e-bf9c-59f2-b45b-da613d8651c0)

Appendix (#u34245cca-becb-5aa5-ab35-8a1818d5f01c)

Introduction (#ulink_761762f2-38bf-527b-b98b-30841752e005)

The Ipcress File was my first attempt to write a book. I was a commercial artist, or ‘illustrator’ as we are now called. I had never been a journalist or reporter of any kind so I was unaware of how long writing a book was likely to take. Knowing the size of the task is a deterrent for many professional writers, which is why they defer their ambitions often until it is too late. Being unaware of what’s ahead can be an advantage. It shines a green light for everything from enlisting in the Foreign Legion to getting married.

So I stumbled into writing this book with a happy optimism that ignorance provides. Was it a depiction of myself? Well, who else did I have? After completing two and a half years of military service I had been, for three years, a student at St. Martin’s School of Art in Charing Cross Road. I am a Londoner. I grew up in Marylebone and once art school started I rented a tiny grubby room around the corner from the art school. This cut my travelling time back to five minutes. I grew to know Soho very well indeed. I knew it by day and by night. I was on hello, how are you? terms with the ‘ladies’, the restaurateurs, the gangsters and the bent coppers. When, after some years as an illustrator, I wrote The Ipcress File much of its description of Soho was the observed life of an art student resident there.

After three years postgraduate study at the Royal College of Art I celebrated by impulsively applying for a job as flight attendant with British Overseas Airways. In those days this provided three or four days stop-over at the end of each short leg. I spent enough time in Hong Kong, Cairo, Nairobi, Beirut and Tokyo to make good and lasting friendships there. When I became an author, these background experiences of foreign people and places proved of lasting benefit.

I don’t know why or how I came to writing books. I had always been a dedicated reader; obsessional is perhaps the better word. At school, having proved to be a total dud at any form of sport – and most other things – I read every book in sight. There was no system to my reading, nor even a pattern of selection. I remember reading Plato’s The Republic with the same keen attention and superficial understanding as I read Chandler’s The Big Sleep and H.G. Wells’ The Outline of History and both volumes of The Letters of Gertrude Bell. I filled notebooks as I encountered ideas and opinions that were new to me, and I vividly remember how excited I was to discover that The Oxford Universal Dictionary incorporated thousands of quotations from the greatest of great writers.

So I wasn’t taking myself too seriously when, as a holiday diversion, I took a school exercise book and a fountain pen, and started this story. Knowing no other style I did it as though I was writing a letter to an old, intimate and trusted friend. I immediately fell into the first person style without knowing much about the literary alternatives.

My memory has always been unreliable, as my wife Ysabele regularly points out to me, but I am convinced that this first book was influenced by my time as the art director of an ultra-smart London advertising agency. I spent my days surrounded by highly educated, witty young men who had been at Eton together. We relaxed in leather armchairs in their exclusive Pall Mall clubs. We exchanged barbed compliments and jocular abuse. They were kind to me, and generous, and I enjoyed it immensely. Later, when I created WOOC(P), the intelligence service offices depicted here, I took the social atmosphere of that sleek and shiny agency and inserted it into some ramshackle offices that I once rented in Charlotte Street.

Using the first person narrative enabled me to tell the story in the distorted way that subjective memory provides. The hero does not tell the exact truth; none of the characters tell the exact truth. I don’t mean that they tell the blatant self-serving lies that politicians do, I mean that their memory tilts towards justification and self-regard. What happens in The Ipcress File (and in all my other first-person stories) is found somewhere in the uncertainty of contradiction. In navigation, the triangle where three lines of reference fail to intersect is call a ‘cocked hat’. My stories are intended to offer no more precision than that. I want the books to provoke different reactions from different readers (as even history must do to some extent).