По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

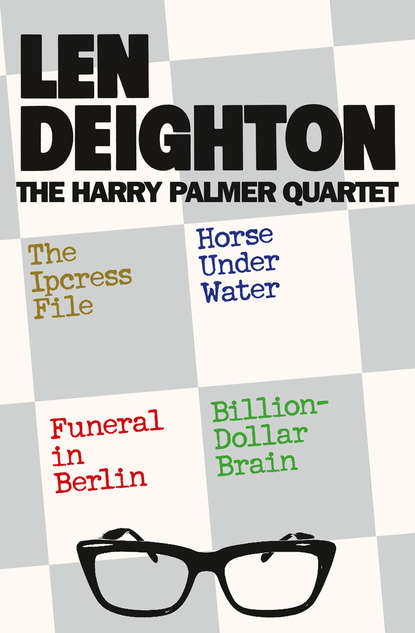

The Harry Palmer Quartet

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Whoever had slaughtered Charlie was there after me, and when the police had finished taking my description from the whimpering woman on the stairs, they’d be after me, too. Dalby’s organization was the only contact with enough power to help me.

At Cambridge Circus I jumped on a bus as it came past. I got off at Piccadilly, hailed a cab to the Ritz, and then walked east up Piccadilly. No car could follow without causing a traffic sensation by an illegal right turn. Just to be on the safe side, I hailed another cab on the far side of the road, outside Whites, in case anyone had done that turn, and now sped in the opposite direction to anyone who could have followed me. I gave the cabbie the address of a car hire company in Knightsbridge. It was still only 5.25.

Not without difficulty, I hired a blue Austin 7, the only car they had with a radio. I used Charlie’s driving licence, and some envelopes I’d found in his wallet ‘proved’ my identity. I cursed my foolishness in not having taken a driving licence from the safe deposit. I was taking a long chance on Charlie’s name not being released to the Press before the various Intelligence departments had a look in, but I tuned in to the 6 o’clock news just the same. Algeria, and another dock strike. The dockers didn’t like something again. Perhaps it was each other. No murders. An antique Austin 7 in front of me signalled a right turn. The driver had shaved under the arms. I drove on through Putney and along the side of the common. It was green and fresh and a sudden burst of sunshine made the wet trees sparkle, and turned the spray from speeding tyres into showers of pearls. Rich stockbrokers in white Jaguars and dark-green Bentleys played tag and wondered why I’d intruded into their private fun.

‘Waaa Waaa Waaa Waaa – you’re driving me crazy,’ sang the radio as I changed down to negotiate Wimbledon Hill, and outside, the nightmare world of killers, policemen and soldiers happily brushed shoulders. I gazed out on it from the entirely imaginary security of the little car. How long was it to be before every one of the crowds on Wimbledon High Street were going to become suddenly interested in Charlie Cavendish and interested even more in finding me. The pianist at the ‘Tin-Tack Club’; I suddenly remembered that I still owed him thirty shillings. Would he give my description to the police? How to get out of this mess? I looked at the grim rows of houses on either side of me and imagined them all to be full of Mr Keatings. How I wished I lived in one – a quiet, uneventful, predictable existence.

Now I was back on the Kingston by-pass at Bushey Road. At the ‘Ace of Spades’ the road curves directly into the setting sunlight, and the little car leapt forward in response to a slight touch of the foot.

Two trucks were driving neck and neck ahead of me. Each one was doing twenty-eight mph, each grimly intent on proving he could do twenty-nine! I passed them eventually and fell in behind a man in a rust-coloured pullover and Robin-Hood hat who had been to BRIGHTON, BOGNOR REGIS, EXETER, HARLECH, SOUTHEND, RYDE, SOUTHAMPTON, YEOVIL and ROCHESTER, and who, because of this, could not now see through his rear window.

At Esher I put on the lights, and well before Guildford the gentle smack of raindrops began to hit the windscreen. The heater purred happily, and I kept the radio tuned to the Light for the 6.30 bulletin. Godalming was pretty well closed except for a couple of tobacconists, and at Milford I slowed up to make sure I took the right route. Not the Hindhead or Haslemere road, but the 283 to Chiddingfold. A hundred yards before I reached the big low Tudor-fronted inn I flashed the headlights and got an answering signal from the brake-actuated red rear lights of a parked vehicle there. I glimpsed the car, a black Ford Anglia with a spotlight fixed to the roof. I watched the rear-view mirror as Mr Waterman pulled his car on to the road just behind me.

I’d been to Dalby’s home once before, but that was in daylight, and now it was quite dark. He lived in a small stone house lying well back from the road. I backed, just off the road, up a small driveway. Waterman parked on the far side of the road. The rain continued, but wasn’t getting any worse. I left the car unlocked with the keys on the floor under the seat. Waterman stayed in his car and I didn’t blame him. It was 6.59, so I listened to the 7 o’clock news bulletin. There was still no mention of Charlie, so I set off up the path to the house.

It was a small converted farm-house with a décor that writers in women’s magazines think is contemporary. Outside the mauve front door there was a wheelbarrow with flowers growing in it. Fixed to the wall was a coach lamp converted to electricity, not as yet lit. I knocked at the door with, need I say it, a brass lion’s-head knocker. I looked back. Waterman had doused his lights, and gave me no sign of recognition. Perhaps he was smarter than I thought. Dalby opened the door and tried to register surprise on his bland egg-like public school face.

‘Is it still raining?’ he said. ‘Come in.’

I sank into the big soft sofa that had Go, Queen and Tatler scattered across it. In the fireplace two fruit-tree logs sent an aroma of smoky perfume through the room. I watched Dalby with a certain amount of suspicion. He walked towards a huge bookcase – the aged spines of good editions of Balzac, Irving and Hugo glinted in the fire-light.

‘A drink?’ he said. I nodded, and Dalby opened the ‘bookcase’ which proved to be an artful disguise for doors of a cocktail cabinet. The huge glass and mirror box reflected a myriad of labels, everything from Charrington to Chartreuse – this was the gracious living I had read about in the newspapers.

‘Tio Pepe or Teachers?’ asked Dalby, and after handing me the clear glass of sherry added, ‘I’ll have someone fix you a sandwich. I know that having a sherry means you are hungry.’ I protested, but he disappeared anyway. This wasn’t going at all the way I planned. I didn’t want Dalby to have time to think, nor did I intend that he should leave the room. He could phone – get a gun … As I was thinking this, he reappeared with a plate of cold ham. I remembered how hungry I was. I began to eat the ham and drink my sherry, and I became angry as I realized how easily Dalby had put me at a disadvantage.

‘I’ve been bloody well incarcerated,’ I finally told him.

‘You’re telling me,’ he agreed cheerfully.

‘You know?’ I asked.

‘It was Jay. He’s been trying to sell you back to us.’

‘Why didn’t you grab him?’

‘Well, you know Jay, he’s difficult to get hold of, and anyway, we didn’t want to risk them “bumping you off” did we?’ Dalby used expressions like ‘bumping off’ when he spoke to me. He thought it helped me to understand him.

I said nothing.

‘He wanted £40,000 for you. We think he may have Chico, too. Someone in the USMD

(#ulink_3ebae2af-3f4b-5779-8a4b-bbde3337d925) works for him. That’s how he got you from Tokwe. It could be serious.’

‘Could be?’ I said. ‘They damn’ nearly killed me.’

‘Oh, I wasn’t worried about you. They were unlikely to kill the goose and all that.’

‘Oh, weren’t you? Well you weren’t there to get worried and all that.’

‘You didn’t see Chico there?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘That was the only alleviating feature of the whole affair.’

‘Another drink?’ Dalby was the perfect host.

‘No,’ I said. ‘I must be getting along. I want the keys to the office.’ His face didn’t flicker. Those English public schools are worth every penny.

‘I insist that you join us for dinner,’ said Dalby.

I declined and we batted polite talk back and forth. I wasn’t out of the wood yet. Charlie was dead, and Dalby either didn’t know or didn’t want to talk about it. As I was about to tell him Dalby produced from an abstract painting that concealed a wall safe, a couple of files about payments to agents working in the South American countries.

(#ulink_b01fadd5-6ccf-5dcd-a466-1ea0f5f260a8) Dalby gave me both files, and the keys, and I promised to figure out something for him by ten o’clock the next morning at Charlotte Street. I looked at my watch. It was 7.50 P.M. I was pretty anxious to leave because Waterman’s instructions were to come at the run after one hour exactly. From his performance so far it seemed unwise to count on him being tardy. I took my leave, still without the name of Charlie Cavendish being mentioned. I decided to leave it until we were in the office.

Half-way down the driveway I realized that between now and tomorrow morning was ample time to get myself arrested on a murder charge. Perhaps I should go back and say, ‘Oh, there’s one other thing. I’m wanted for murder.’

I started up the Austin, and moved easily down the road towards the big pub. It was about a quarter of a mile down the road before Waterman switched on his lights. He kept going up in my estimation. When we got to the car park of the ‘Glowering Owl’, I walked across to Waterman and gave him the money in cash.

‘It went off all right then. I’m glad of that,’ he said, his nicotine-stained moustache following his mouth as it smiled. I thanked him, and he put his car into gear, then said, ‘I thought we were in for a right barny when the big Chink feller came out to look at you through the window.’

Big rain clouds raced across the moon, and an arty-looking couple came out of the Saloon Bar, arguing violently. They walked across the car park.

‘Wait a minute,’ I said, my hand on the edge of the wet car window. ‘Chink? A Chinese? Are you sure?’

‘Am I sure? Listen, friend. I had five years in the New Territories; I should know what a Chink looks like.’

I got into the car seat beside him, and asked him to go through it in slow motion. He did so, but he needn’t have done for all the extra information it gave me.

‘We are going back up there right away,’ I told him.

‘Not me, friend, I did the job I was hired for.’

‘OK,’ I said, ‘I’ll pay you again.’

‘Look friend, you’ve been there, you’ve had your say – let things be.’

‘No, I must go back up there whether you come or not. I might only glance in through the window,’ I coaxed.

‘This is nothing to do with your wife, friend. You’re up to some no-good. I can tell. I could tell you weren’t a divorce case from the first minute I saw you.’

‘All right,’ I said, ‘but my money’s OK isn’t it?’ I didn’t pause, as I considered his disagreement on this score very unlikely. ‘I’m from Brighton – Special Branch,’ I improvised, and showed him my forged warrant card. It passed in the poor light inside the car, but I’d hate to depend upon it in daylight.

‘You a copper! You never are, friend.’

I persisted that I was, and he half-believed me. He said, ‘I know that some of the new coppers you can hardly tell nowadays. Real mixture they are.’

‘This is an important case,’ I told him. ‘And I want your assistance now.’

The squeelch and buzz of the windscreen wipers continued steadily as he made up his mind. Why did I want him? I thought; but somewhere I had a hunch it would be a good eight guineas’ worth. It wasn’t one of my best hunches.