По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

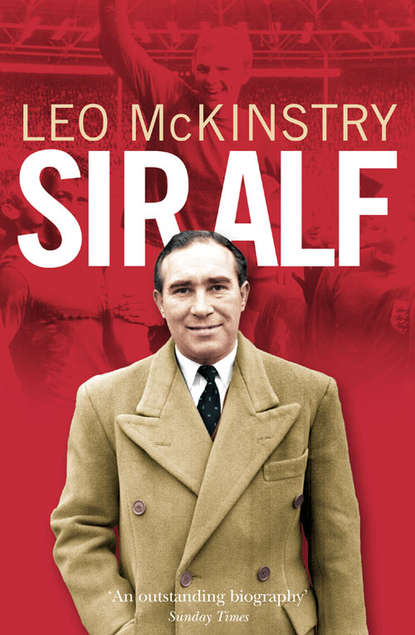

Sir Alf

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Alf agreed to meet Dodgin in a sandwich bar at Waterloo, just the sort of mundane venue with which he was most comfortable throughout his life. Dodgin told Ramsey that they were prepared to pay him the weekly sum of £4 in the summer, £6 in the season, and £7 if he got into the League. With his characteristic mix of self-confidence and wariness, Alf told the Southampton manager that the offer was not good enough. ‘I wanted to start a career in football – but not on £4 a week,’ he explained later. It is a measure of Alf’s importance to the club that his strategy worked. He was invited down to the Dell and offered enhanced terms: £6 in the summer, £7 in winter and £8 if he got into the League side. This time he accepted.

But immediately after he signed, his concerns about money again came to the surface. Because in the summer of 1946 he was still officially in the armed forces, awaiting demobilization, Alf did not receive the £10 signing-on fee to which professionals would normally be entitled in peacetime. In his 1952 book, Talking Football, Alf claimed, ‘That did not matter.’ The reality was very different. Alf was actually furious at missing out on his £10. Mary Bates, who had taken up her position as Southampton’s Assistant Secretary in August 1945 after working for the Labour Party in Clement Attlee’s landslide general election victory, has this recollection:

£10 was quite a lot at that time. And this day he came to sign as a professional. When he arrived in the office he was in his infantry gear.

‘What are you doing in your uniform?’

‘I haven’t quite left the army yet.’

‘Well, until you do, I can’t pay your signing on fee. You’ll have to wait until you’re demobbed before I can officially sign you on. Those are my instructions.’

He nearly went beserk at those words. He was so upset. He had obviously been expecting the money. It was very unlike Alf, who was normally so calm. He was usually very nice, gentlemanly. But he did almost lose his temper on this occasion. He was usually very pleasant, but he was not very pleasant about losing his £10.

After seven years of disruption, the Football League officially resumed in August 1946. But, after all the drawn-out negotiations over Alf’s contract, it was hardly a glorious return to professional football for him. Still unclear about his correct position, he began the season in the reserves. In the autumn, however, coach Bill Dodgin and trainer Syd Cann made a crucial move, one that was to completely change Alf’s playing career. Sensing that Alf was uncomfortable at both centre-forward and centre-half, they suggested that he moved to right-back. It was exactly the right place for Alf, one that exploited his ability to read the game, to judge the correct moment for intervention and to make the telling pass.

Though he had been a fine footballer in his youth, he had never been blessed with the sort of exceptional natural talent which defines true greatness. After all, he had never fulfilled his ambition to play for London Schoolboys; nor had any League club shown any serious interest in him before the war; and his performances with Southampton since 1943 had been inconsistent. His prowess on the field had lain more in his mental strengths: his coolness under pressure, the respect from other players and his gift of anticipation. Now, with a characteristic spirit of determination, Alf set about moulding himself for his new role at full-back. He sought to improve his technique with long hours of practice on the training ground, working particularly on the accuracy and power of his kicks. He raised his fitness levels, not just by training in the gym, but also by taking long walks through the Southampton countryside. Above all, he strove to develop a new tactical awareness. Fortunately for Alf, the trainer at Southampton, Syd Cann, had been a full-back with Torquay United, Manchester City and Charlton, and was therefore able to pass on the lessons of his experience through practice sessions and numerous talks over a replica-scale pitch – measuring one inch to the yard – in the dressing-room at the Dell. The master and pupil developed a close relationship, as Cann later recalled in a BBC interview:

My first memories of Alf were as a centre-forward. He played several times there in the reserves, not too successfully, and I felt that perhaps he had better qualities to play as a full-back. And after discussions with the manager Bill Dodgin, we decided to try him in this position. We spent a lot of time in discussions, Alf and I. He was a very keen student. He wanted to learn about the game from top to bottom. We had a football field painted on the floor of the dressing-room at Southampton and Alf came back regularly in the afternoons, spending hours discussing techniques and tactics. I have never known anyone with the same sort of application, with the same quickness of learning as Alf Ramsey. He would never accept anything on its face value. He had to argue about it and make up his own mind. And once he had made up his mind that this was right, it was put into his game immediately. I spent hours on the weaknesses and strengths of his play. He accepted, for instance, that he was inclined to be weak on the turn on and in recovery. So we worked on that so he became quicker in recovery. Very rarely was he caught out. He was the type of player who was a manager’s dream because you could talk about a decision and he would accept it and there it was, in his game.

Ramsey’s diligence soon had its reward. On 26 October 1946 Alf was selected for Southampton’s Division Two game at home to Plymouth, after the regular right-back Bill Ellerington had picked up an injury. Eight years after that fruitless approach from Portsmouth, Ramsey was finally about to play League football, and he was understandably nervous. When Saturday afternoon arrived, however, he was helped by the reassuring words of his fellow full-back and Saints captain Bill Rochford: ‘You’re not to worry out there. That’s my job. It’s another of my jobs to put you right, so always look to me for any guidance.’ That encouragement was very different to the ridicule often accorded to debutants. But then Rochford was very different to the cynical old pro more worried about his own place than the fortunes of the side. Uncompromising, passionate, selfless, he was hugely admired by his fellow Southampton players. ‘He was the Rock of Gibraltar,’ says Eric Day. Bill Ellerington, Alf’s rival for the right-back position, reflects:

Bill Rochford was my mentor. We called him Rocky. He was a good captain. It’s easy to be a good captain when you’re winning. But when the chips were down, Bill was great at keeping us going. He could tear you off a few strips. Once against Bradford we were winning 3-0 with only about ten minutes to go and I flicked the ball nonchalantly back to the keeper and it went out for a corner. 3-1. Then they had a free kick. 3-2. We managed to win with that score but afterwards Bill tore me to shreds for being casual. He was right.

Rochford’s guidance helped Alf through his first game, as Southampton won easily. ‘Steady Alf, I’m just behind you,’ the captain would shout during the game. But Alf quickly recognized how deep was the gulf between the League and the type of soccer he had previously experienced. Alf wrote in Talking Football:

It dawned on me how little about football I know. Everybody on the field moved – and above all else thought – considerably quicker than did I. Their reactions to moves were so speedy they had completed a pass, for instance, while I was still thinking things over.

After one more game in the first team, Alf was sent back to the reserves once Bill Ellerington had recovered.

It was inevitable that Alf should find it a struggle at first to cope. The only answer was yet more practice, learning to develop a new mastery of the ball and a more sophisticated approach. Again, he was indebted to the influence of his captain Bill Rochford:

Playing alongside him made me realize that there was considerably more to defending than just punting the ball clear, as had become my custom. During a match I made a mental note of how Rocky used the ball; the manner in which he tried to find a colleague with his clearances; the confidence he always displayed when kicking the ball at varied heights and angles.

The great difficulty for Alf was that, no matter how much he improved his game, his path back to the first team was blocked by Bill Ellerington, who was one of the best full-backs in the country and would, like Alf, win England honours in that position. ‘Bill was a great tackler and a terrific kicker of the ball. He could kick from one corner flag to the opposite corner, diagonally, a good one hundred yards – and that was with one of those big heavy old balls,’ says Ted Ballard, another Southampton defender of the era.

Alf managed to play a few more first-team games that year but his big break game in January 1947, in rather unfortunate circumstances for Bill Ellerington. That winter was the bitterest of the 20th century. Week upon week of heavy snow hampered industry, disrupted public transport and so seriously threatened coal supplies that the Attlee government was plunged into crisis. More than two million men were put out of work because of the freeze, while severe restrictions were placed on the use of newsprint. Football, too, was in crisis. In the Arctic conditions, 140 matches had to be postponed. In the games that went ahead, the lines on the icy pitches often had to be marked in red to make them clear. Such was the public frustration at the lack of football that when Portsmouth managed to melt the snow at Fratton Park using a revolutionary steam jet, the club was rewarded with a crowd of 11,500 for a reserve fixture.

The freeze also had a direct effect on Alf’s career. Towards the end of January, Southampton went to the north-east resort of Whitley Bay, in preparation for a third-round FA Cup tie against Newcastle. Alf, as so often at this time, was a travelling reserve. One afternoon, the senior players went out golfing. In the cold weather, most of them wore thick polo-neck jerseys – except Bill Ellerington, who braved the course in an open-neck pullover. That night ‘Big Ellie’ felt terrible; he woke up the next morning wringing wet. He was rushed to hospital, where he was quickly diagnosed to be suffering from pneumonia. ‘I completely collapsed and ended up in hospital for three months. I did not come out until April,’ says Ellerington. One man’s tragedy is another’s opportunity. Alf was drafted into the side against Newcastle, and he showed more confidence than he had previously displayed, though he was troubled by Newcastle’s left-winger, Tommy Pearson, as the Saints lost 3-1 in front of a crowd of 55,800, by far the largest Alf had ever experienced.

With Ellerington incapacitated, Alf was guaranteed a good run in the side, and he kept his place for the rest of the season, growing ever more assured with each game. In February 1947 the Daily Mirror predicted that ‘only a few weeks after entering the big time, Alfred Ramsey is being talked of as one of the coming men of football’. The paper went on to quote coach Bill Dodgin, who paid tribute to Alf’s dedication: ‘You can’t better that type of player. The player who thinks football, talks football and lives football is the man who makes good.’

One particularly important match for Alf took place at the Dell in April against Manchester City, when he had the chance to witness at first hand City’s veteran international full-back Sam Barkas, who, at the age of 38, was playing his last season. Ramsey was immediately captivated by the skills of Barkas and decided to make him his role model. ‘It was the most skilful display by any full-back I had seen,’ he told the Evening News in 1953. ‘The brilliance of Barkas’ positional play, his habit of making the other fellow play how he wanted him to play, all caught my eye. What impressed me most of all was Sam Barkas’ astute use of the ball. Every time he cleared his lines he found an unmarked colleague,’ he wrote later.

Exactly the same attributes were to feature in Ramsey’s play over the next eight years; one of Alf’s greatest virtues was his ability to absorb the lessons of any experience. In his quest for perfection, he was constantly watching and learning, experimenting and practising. As Ted Bates put it in an interview in 1970:

Alf was very single-minded. He would come to the ground for training and he wanted to get on with it – no messing about. I believe he was a bit immature then but you could not dispute his single-mindedness. He sole interest was in developing his own game. He was the original self-educated player – all credit to him for that. But he always had this polish – it is the only word – and it made him stand out in any team.

Alf’s soccer intelligence, allied to a phenomenal dedication to his craft and an unruffled temperament, made him a far more effective player than his innate talent warranted. Eric Day says:

He had a very, very good football brain. If he hadn’t, he would not have played where he did, because he was not the most nimble of players. Not particularly brilliant in the air, because he did not have the stature to jump up. But he was a decent tackler and a great passer. He could read the game so well, that was his big asset. That was why he became such a great manager.

Ted Ballard has the same assessment:

He was a great player, a super player. He was a quiet man, very strict on himself, very sober and trained hard. The only thing he lacked was pace; he could be a bit slow on the turn because he was built so heavily round the hip. But he made up for it with the way he read the game so well.

Stan Clements, who played at centre-half and was himself a shrewd judge of the game, told me:

He was two-footed. You would not have known the difference between one foot and the other. He was a tremendously accurate passer. When he kicked the ball, it went right to the other player’s foot. All the forwards in front of him always said that when Alf gave them the ball, it was easy to collect. They liked that because they could pick it up in their stride. His judgement of distance, his sense of timing was just right. The point about Alf was that he was so cool. One of the remarkable things about him was that at free-kicks and corners, when the goalmouth was crowded, he seemed to have the ability almost to be a second keeper on the goal-line. He seemed always to be able to read exactly what was going on. His anticipation was superb. He was always in the right position to chest the ball down and clear it. He must have saved us at least a goal every other game. He understood football better than most people. I always knew he would make a good manager, because of his ability to size up the game. Bill Dodgin and Syd Cann, the trainer, used to have this layout on the floor of our dressing-room, with counters for the players. And they would use this to analyse our tactics, especially in set-pieces. Alf was always very good at understanding all that; he would take it all on board quickly.

Alf was so dedicated that, even at the end of the 1946-47 season, when he returned to Dagenham, he carried on practising in the meadows behind his parents’ cottage: ‘I used to take a football every morning during those months of 1947 and spend an hour or two trying hard to “place it” at a chosen spot.’ Alf knew that only by developing his accuracy would he be successful in adopting the Sam Barkas style of constructive defence. The hard work paid off, and Alf did not miss a single game during the 1947-48 season; indeed, he was the only Southampton player to appear in all 42 League fixtures. Such was the strength of Ramsey’s performances that Bill Ellerington, who had gradually recovered from his illness, could not force his way back into the side, though, as he told me, that did not lead to any personal resentment:

I was working hard to get back. I am not being heroic but it was either that or packing the game in. But Alf was playing really well. He was a good reader of the game, a good player of the ball in front of him. A bit slow on the turn but he was made that way. On tackling, he knew when to go in and not to go in. And he made more good passes than most players. He was always cool. There was no personal rivalry between us. I never even dreamed about animosity or anything like that. We were just footballers. Mind you, looking back, Alf was ambitious. He was a hard lad to get to know. He was not stand-offish, but you could never get at him. He was not one of the boys. We travelled everywhere by train in those days, and I was part of a card school, but Alf did not join in. He never got in trouble, because he was not interested.

As Bill Ellerington indicates, Alf’s personality did not change much once he became a successful professional. He remained undemonstrative, reserved, unwilling to mix easily. ‘He would not go out of his way to talk to anybody,’ recalled Ted Bates, ‘but if you wanted his advice, he’d give it. When we played, early on, I roomed with him, and he was always the same, very quiet, getting on with his job.’ Eric Day, the Southampton right-winger, used frequently to catch the train from Southampton to London because his parents lived in Ilford:

I saw him a lot but there was never much conversation. I am not a great talker and Alf certainly wasn’t one. Whenever we chatted, it was only ever about football. He could be a bit short with people, though he was never rude. Alf didn’t suffer fools gladly, I’ll tell you that. He was a bit secretive; he just didn’t chat. Maybe that’s because he was a gypsy. Gypsies are extremely close-knit; they keep it in the family. You never heard him shouting, not on the field or in the dressing-room or on the train. If he had any strong feelings about anyone, he just kept them to himself. He was a very honest bloke. He did not like talking about people behind their backs. You never heard him tear anyone to shreds. He was very modest. There was nothing of the star about him.

The Southampton goalkeeper of the time, Ian Black, highlights similar traits:

Once he had finished training, you seldom saw him. That is fair enough. People are made in different ways. But it did not make him any the less likeable. I think he had quite a shy nature; he was friendly enough but he did not like much involvement with others. Though he would talk plenty about the game, he was not much of a conversationalist otherwise.

Throughout his time at Southampton, Ramsey lived in digs owned by the club, which he shared with Alf Freeman, one of the Saints’ forwards. The two Alfs had served together in the Duke of Cornwall’s Regiment, though Freeman had seen action in France and Germany in 1944-45. Now in his mid-eighties and with his powers of communication in decline, Freeman still retains fond memories of living with Alf:

We had good times together in the army. We were pretty close then. In our Southampton digs, we were looked after well by our landlady. Alf was a lovely man but he was very, very quiet. He was shy and never talked much. Unlike most of us players, he did not smoke or drink much. He always dressed smartly. He liked the cinema, and also did a lot of reading, mainly detective stories.

The late Joe Mallet, who was one of Southampton’s forwards, told Alf’s previous biographer in a powerfully worded statement that Ramsey and Freeman had fallen out:

They were close but they had a disagreement and though they lived together Alf would never speak to Freeman. If you got on the wrong side of Alf, that was it, you were out! You couldn’t talk him around; he would be very adamant. If he didn’t like somebody or something, he didn’t like them. There were no half measures! He was a man you could get so far with, so close to, and then there was a gap, he’d draw the curtain and you had to stop. I don’t think he liked any intrusion into his private life. Alf wouldn’t tolerate anything like that. He’d be abusive rather than put up with it.

But today Freeman has no recollection of any such dispute: ‘There was never any trouble between us. I don’t know where Joe Mallet got that stuff about a disagreement. That just wasn’t true. I always got on well with Alf. He was a good man to me. I liked him very much.’

Pat Millward came to know Ramsey better than most through Alf’s friendship with her husband Doug, who played for both the Saints and Ipswich. Though she recognizes that Alf’s diffidence could come across as offensive, she personally was a great admirer:

People used to think that Alf was difficult because he did not have a lot to say. He would just answer a question and then walk away. A lot of people did not like him. They thought he was too quiet, too pleased with himself. ‘He fancies himself, doesn’t he? Who does he think he is?’ they would say, without really knowing him. But I loved him. He was just the opposite of what some people thought. He was down-to-earth, never bragged, never put on airs, never went for the cheers. And he was such a gentleman, always polite and well-mannered. I remember I was working in the restaurant of a department store in Southampton, and the store had laid on an event for the players, where they were all to receive wallets, and their wives handbags. The gifts were set out on two stands and the players could take their choice. Alf was among the first to arrive. But he held back until all the rest of them had taken what they wanted.

‘Shouldn’t you get your wallet?’ I asked.

‘No, Pat, it’s fine. Let the others get theirs.’

He was a special man. Doug thought the world of him. He was never a joker, but if he liked you, he showed it. On the other hand, if he didn’t like you, he had a way of ignoring you.

Revelling in professional success, Alf was more fixated with soccer than ever. But he still enjoyed some of the other pursuits of his youth, like greyhound racing and cricket. Bill Ellerington recalls:

We would often go to the dog track near the Dell on Wednesday evenings and Alf would come with us. Looking back, he was a very good gambler. There would be six races, six dogs each, and Alf would just go for one dog. Whatever the result, win or lose, he finished. He was not like most of the boys, chasing their money. He was very shrewd. At the time, I just accepted it, but looking back, it showed how clever he was. I always felt there was a bit of the gambler about him, even when he was England manager in the 1966 World Cup. He had this tremendous, quiet self-confidence about him.

Stan Clements also remembers Alf’s enthusiasm for the dogs, but feels that Alf’s lack of social skills has been exaggerated:

Alf was a nice fella once you knew him, easy to get on with. He had worked for the Co-op and was good with figures. His family were involved in racing greyhounds, in fact some of them used to live on that, so he knew about gambling. At that time in the late 1940s, dog-racing was extremely popular; it was a cheap form of entertainment for the working-class. Alf would usually go to the dogs on a Wednesday with Alf Freeman. He was also good on the horses. He was very quick at working out the odds. He was not tight with his money, or anything like that. He was quite prepared to open his wallet. He was a cool gambler; you never saw him get excited. He would put his bets on in a controlled manner. He would assess the situation. He could lose without it affecting him. In everything he did, he was never over-the-top. He always had control of himself. He enjoyed a drink, but he was not a six pints man.