По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

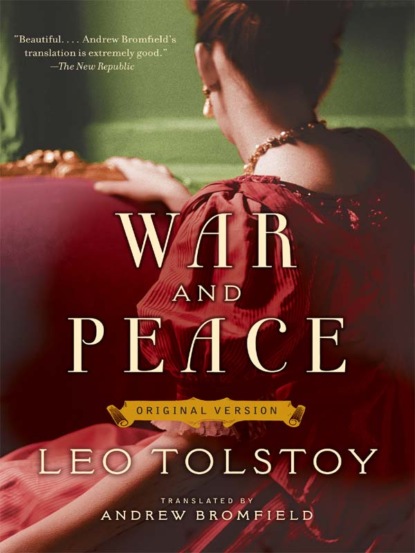

War and Peace: Original Version

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The remaining infantry hurriedly crossed the bridge, funnelling in tightly at the entrance. Eventually the carts all got across, the crush became less heavy and the final battalion stepped onto the bridge. Only the hussars of Denisov’s squadron were left at the other end of the bridge to face the enemy. The enemy, visible in the far distance from the facing mountain, could still not be seen from the bridge below, since the horizon of the depression along which the river flowed was bounded by the opposing elevation at a distance of no more than half a verst. Ahead of them lay a wasteland, across which a mounted patrol of our Cossacks was moving here and there in little clusters. Suddenly troops in blue coats and artillery appeared on the opposite elevation of the road. It was the French. The Cossack patrol withdrew downhill at a canter. All the officers and men of Denisov’s squadron, although they tried to talk about something else and look somewhere else, could not stop thinking about what was up there on the hill, and they all kept glancing constantly at the spots of colour appearing on the horizon, which they recognised as enemy troops. After midday the weather had cleared up again, the sun was bright as it moved lower over the Danube and the dark mountains surrounding it. It was quiet, and occasionally the sounds of horns and the shouts of the enemy reached them from that mountain. There was no one left now between the squadron and the enemy soldiers, apart from small mounted patrols. An empty space, about three hundred sazhens across, separated them from the enemy, who had stopped firing, so that the stern, menacing, unassailable and imperceptible line that separates two hostile forces could be sensed even more clearly.

A single step across that line, which resembles the line separating the living from the dead, and there is the mystery of suffering and death. And what is over there? Who is there? There, beyond this field and village and roof lit up by the sunlight? Nobody knows, you want to know and at the same time you are afraid to cross this line, and you want to cross it, and you know that sooner or later you will have to cross it and learn what is over there, on the far side of the line, just as you will inevitably learn what is over there, on the far side of the death. And you are so strong, healthy, merry and excited and surrounded by such healthy and boisterously excited men. Although no one thinks this, every man senses it when he is within view of the enemy, and this feeling lends a particular brilliance and joyful clarity to the impressions of everything that takes place at such moments.

The smoke-puff of a shot appeared on a hillock beside the enemy and the shot whistled over the heads of the squadron of hussars. The officers, who had been standing together, each went to their own places and the hussars began painstakingly drawing the horses up in lines. Everyone in the squadron fell silent. They all kept glancing straight ahead at the enemy and the squadron commander, waiting for the command. Another shot, the third, flew past. It was obvious that they were firing at the hussars; but the shot flew past over the hussars’ heads with a swift, uniform whistle and struck somewhere behind them. The hussars did not look round, but every time there was the sound of a shot flying over, the whole squadron, with its faces that were all identical but different, and its trimmed moustaches, held its breath as if by command while the shot was in the air and, tensing the muscles of all its legs in their tight blue breeches, half-stood in the stirrups and then sank down again. Without turning their heads, the soldiers squinted sideways at each other, curious to spy out the impression made on their comrades. On every face, from Denisov to the bugler, the single common expression of the struggle between irritation and excitement appeared around the lips and the chin. The sergeant-major frowned, surveying the soldiers as though he were threatening them with punishment. The cadet Mironov bent down every time a shot flew over. Rostov, standing on the left flank on his mount Grachik, handsome but with the bad legs, had the happy air of a pupil called out in front of a large audience to answer an examination question in which he was certain that he would distinguish himself. He glanced round at everyone with a clear, bright gaze, as though asking them to notice how calmly he stood his ground under fire. But in his face also, even against his will, that same expression of something new and stern appeared around the mouth.

NAPOLEON IN 1807 Engraving by Debucourt (#ulink_2b01bdcf-01ea-5923-acbc-754f92d29119)

“Who’s that bowing over there? Cadet Miwonov! That won’t do, look at me!” shouted Denisov, who could not stay still and was whirling round on his horse in front of the squadron. Vaska Denisov’s face, with its snub nose and black hair, and his entire stocky little figure with the short, hair-covered fingers of the sinewy hand in which he was grasping the hilt of his drawn sabre, was exactly the same as it always was, especially in the evening after he had drunk two bottles. He was only redder than usual and, throwing his shaggy head back and up as birds do when they sing, pressing his spurs mercilessly into the sides of his good Bedouin with his small feet and appearing to fall backwards, he galloped off to the other flank of the squadron and shouted in a hoarse voice that they should inspect their pistols. As he rode by he glanced at the handsome officer Peronsky in the rear and hastily turned away.

In his semi-dress hussar uniform, on his steed that cost thousands, Peronsky was very handsome. But his handsome face was as white as snow. His thoroughbred stallion, hearing the terrible sounds above its head, had entered into that fervent fury of the well-trained thoroughbred of which children and hussars are so fond. He kept snorting, jingling the chain and rings of his bit and striking at the ground with his slim, muscular leg, sometimes not reaching it and waving his foot through the air, or, turning his lean head to the right and the left as far as his bit allowed, he squinted at his rider with a black, bulging bloodshot eye. Turning fierily away from him, Denisov set off towards Kiersten. The staff-captain was riding at a walk towards Denisov on a broad, sedate mare. The staff-captain, with his long moustaches, was serious as always, only his eyes were gleaming more than usual.

“What is this?” he said to Denisov. “This action won’t get as far as an attack. You’ll see, we’ll withdraw.”

“God only knows what they’re doing!” shouted Denisov. “Ah! Wostov!” he cried to the cadet as he noticed him. “Well, here you are at last.” And he smiled approvingly as he looked at the cadet, evidently pleased for him.

Rostov felt perfectly happy. Just at that moment the commander appeared on the bridge. Denisov galloped towards him.

“Your excellency! Permission to attack! I’ll thwow them back!”

“What do you mean, attack?” said the commander in a bored voice, frowning as though at some tiresome fly. “And why are you holding position here? Can’t you see the flankers are withdrawing? Pull your squadron back.”

The squadron crossed the bridge and moved out of range without losing a single man. They were followed across by the second squadron, which had been on the skirmish line, and the final Cossacks withdrew, clearing that side of the river.

IX

After crossing the bridge, one after another the two squadrons of Pavlograd Hussars set off back uphill. The regimental commander, Karl Bogdanovich Schubert, came across to Denisov’s squadron and rode at a walk not far from Rostov, not paying the slightest attention to him, even though this was the first time they had seen each other since the old clash over Telyanin. Rostov, feeling that at the front he was in the power of a man whom he now considered himself guilty of offending, kept his eyes fixed on the athletic back, blond head and red neck of the regimental commander. Sometimes it seemed to Rostov that Bogdanich was only pretending not to notice him and that his entire purpose now was to test the cadet’s courage, and he drew himself erect and gazed around cheerfully: sometimes it seemed to him that Bogdanich was deliberately riding close in order to demonstrate his own courage to Rostov. Sometimes Nikolai thought that now his enemy would deliberately send the squadron into a reckless attack in order to punish him. Sometimes he thought that after the attack the commander would walk up to him and magnanimously offer him, now a wounded man, the hand of reconciliation.

Zherkov’s high-shouldered figure, well-known to the Pavlograders, rode up to the regimental commander. After his banishment from the central headquarters staff, Zherkov had not remained in the regiment, saying that he was no fool, to go slaving away at the front, when he would be better rewarded at staff headquarters for doing nothing, and he had managed to obtain a place as an orderly with Prince Bagration. He had come to his former commanding officer with an order from the commander of the rearguard.

“Colonel,” he said with grim seriousness, addressing Nikolai’s enemy and surveying his comrades, “the order is to halt and fire the bridge.”

“Who the ordered?” the colonel asked morosely.

“That I do not know, colonel, who the ordered,” the cornet replied naïvely and seriously, “only that the prince told me: ‘Go and tell the colonel that the hussars must go back quickly and fire the bridge.’”

Following Zherkov, an officer of the retinue rode up to the colonel of hussars with the same order. Following the officer of the retinue, the fat Nesvitsky rode up on a Cossack horse that was scarcely able to carry him at a gallop.

“What’s this, colonel,” he cried as he was still riding up, “I told you to fire the bridge; and now someone’s garbled it, everyone’s going mad up there and you can’t make sense of anything.”

The colonel unhurriedly halted the regiment and turned to Nesvitsky:

“You telled me about the combustible substances,” he said, “but you don’t told me anything about setting fire to them.”

“Come on now, old man,” Nesvitsky said when he came to a halt, taking off his cap and straightening his sweaty hair with a plump hand, “certainly I told you to fire the bridge when you had put the combustible substances in place.”

“I’m not your ‘old man’, mister staff officer, and you did not told me fire the bridge! I know military service, and am in the habit of following strictly orders. You telled me they would set fire to the bridge. How by the Holy Spirit know can I …”

“There, it is always the same,” said Nesvitsky with a wave of his hand.

“What brings you here?” he asked, addressing Zherkov.

“Why, the same thing. But you have become all damp, allow me to wring you out.”

“You said, mister staff officer …” the colonel continued in an offended tone.

“Colonel,” the officer of the retinue interrupted, “you need to hurry, or the enemy will have moved his guns close enough to fire grapeshot.”

The colonel looked without speaking at the officer of the retinue, at the fat headquarters staff officer, at Zherkov and frowned.

“I shall fire the bridge,” he said in a solemn tone of voice as though, despite all the problems they were causing him, this was how he showed his magnanimity.

Striking his horse with his long, well-muscled legs, as if it were to blame for everything, the colonel rode out in front and commanded the second squadron, the very one in which Rostov was serving under Denisov’s command, to go back to the bridge.

“So that’s how it is,” thought Rostov, “he wants to test me!” His heart faltered and the blood rushed to his face. “Then let him look and see if I’m a coward,” he thought.

Again there appeared on all the jolly faces of the men in the squadron the same serious expression that they had worn when they were holding position under fire.

Nikolai kept his eyes fixed on his enemy, the regimental commander, wishing to discover some confirmation of his guesses in his face, but the colonel did not even glance at Nikolai once and he looked stern and solemn, as he always did at the front. The command rang out.

“Look lively, lively now!” said several voices around him. Snagging the reins with their sabres, jangling their spurs in their haste, the hussars dismounted, not knowing themselves what they were going to do. The hussars crossed themselves. Rostov was no longer looking at the regimental commander, he had no time for that. He was afraid, his heart was sinking in fear that he might somehow fall behind the hussars. His hand trembled as he handed his horse to the holder, and he could feel the blood pounding as it rushed to his heart. Denisov rode past him, lounging backwards and shouting something. Nikolai could not see anything apart from the hussars running around him, getting their spurs tangled and jangling their sabres.

“A stretcher!” someone’s voice shouted behind him. Rostov did not think about what the demand for a stretcher meant, he ran, trying only to be ahead of all the others, but just at the bridge, not looking where he was putting his feet, he stepped into the sticky trampled mud, slipped and fell on to his hands. The others ran round him.

“On both sides, captain,” he heard the regimental commander’s voice say. The commander, having ridden forward, had stopped on his horse not far from the bridge with a triumphant, jolly expression.

Rostov, wiping his dirty hands on his breeches, glanced round at his enemy and started running further, assuming that the further forward he went, the better it would be. But Bogdanich, even though he had not been looking and did not recognise Rostov, shouted at him:

“Who’s that running in the middle of the bridge? To the right side! Cadet, come back!” he shouted angrily.

Even now, however, Karl Bogdanovich did not pay any attention to him: but he did turn to Denisov who, flaunting his courage, had ridden on to the boards of the bridge.

“Why take a risk, captain! You should dismount,” said the colonel.

“Eh! It’ll hit whoever it likes,” replied Vaska Denisov, turning round in the saddle.

Meanwhile Nesvitsky, Zherkov and the officer of the retinue were standing together, out of range, and watching either one or another of the small groups of men in yellow shakos, dark-green jackets decorated with tasselled cords and blue breeches fussing about beside the bridge, or watching the far side, where in the distance the blue coats were drawing nearer, and the groups with horses which could easily be taken for gun crews.

“Will they fire the bridge or won’t they? Who’ll be first? Will they get there and fire the bridge, or will the French get within grapeshot distance and kill them all?” Every one of the large number of troops who were standing above the bridge had his heart in his mouth and could not help asking himself this question, and in the bright evening light they watched the bridge and the hussars, and the far side where the blue hoods were advancing with bayonets and guns.

“Oh! The hussars are in for it!” said Nesvitsky. “They’re within grapeshot range now.”

“He shouldn’t have taken so many men,” said the officer of the suite.

“No, he really shouldn’t,” said Nesvitsky. “He could have sent two brave lads, it would have been all the same.”

“Ah, your excellency,” interjected Zherkov, keeping his eyes fixed on the hussars, but still speaking with that naïve manner of his, which made it impossible to guess whether what he said was serious or not. “Ah, your excellency! What a way to think! Send two men, then who’s going to give us an Order of St. Vladimir with a ribbon? But this way, even though they’ll take a drubbing, you can still present the squadron and get a ribbon for yourself. Our Bogdanich knows the ways things are done.”

“Well,” said the officer of the retinue, “that’s grapeshot.” He pointed to the French artillery pieces which were being uncoupled from their limbers and rapidly moving away.