По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

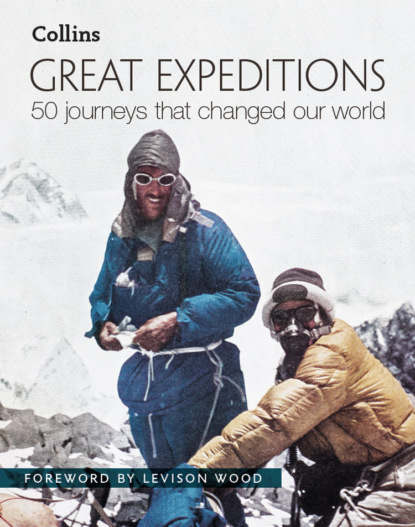

Great Expeditions: 50 Journeys that changed our world

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘They saw no grass, the mountain tops were covered with glaciers.....’

The Greenlanders’ Saga

Leif Eriksson sailing down the Labrador coast, as imagined in a nineteenth-century illustration.

An unpromising land

Now Leif Eriksson, the son of Erik the Red, heard the tale of Bjarni and thought he would like to visit such lands. He visited Bjarni and purchased his boat and recruited a crew of thirty five. The first land they reached was most likely Baffin Island, an inhospitable place according the Saga’s description: ‘They saw no grass, the mountain tops were covered with glaciers, and from sea to mountain the country was like one slab of rock. It looked to be a barren, unprofitable country.’ He called it Helluland (Land of Flat Stones).

They sailed on and saw more land, most likely Labrador, with gently sloping forested land along its coast. This he called Markland (Forest Land). Then they sailed on again and reached more land, first landing on an island, where the Saga recounts that ‘they discovered dew on the grass. It so happened that they picked up some of the dew in their hands and tasted of it, and it seemed to them that they had never tasted anything so sweet.’

The outside of a recreated long house at L’Anse aux Meadows the Viking settlement in north-western Newfoundland, discovered by the Norwegian archaeologist Helge Ingstad in 1960.

A winter of content

They then beached their boat and landed on the mainland. Given the time of year they decided that they would settle here for the winter and return home in the spring. They built turf huts, ate the plentiful salmon from the rivers and lakes, and had a remarkably mild winter (‘there was no frost by night, and the grass hardly withered’). Leif sent out groups to explore the area round about, and on one occasion, a German member of the crew called Tyrkir, was separated and returned later than the rest of his party with the news that he had found grapes and vines. Come spring they loaded the boat with wood and grapes and sailed away from the land Leif called Vinland.

‘There was no lack of salmon in the river or lake, bigger salmon than they had ever seen.’

The Greenlanders’ Saga

Leif ’s brother, Thorvald, then made a trip back to Vinland and settled at the camp Leif had made. For the next two summers they explored the land, only towards the end meeting the native inhabitants. The first they met, they captured and killed and they were then attacked by larger numbers. All survived apart from Thorvald, who died of an arrow wound and was buried in Vinland. The remaining Vikings sailed away the following spring and did not return.

Evidence of the Viking expeditions

In 1960, at the tip of the Great Northern peninsula in the far northwest of Newfoundland, the remains of a Viking settlement was discovered at L’Anse aux Meadows. From their excavations, archaeologists have been able to recreate the turf huts, of typical Viking design, and to date the active life of the settlement from 990 to 1030, which links well with the account of the trips of Leif and Thorvald, as recorded in the Greenlanders’ Saga. Combined, there is sufficient evidence to establish that the Vikings were the first Europeans to reach North America.

Inside of a recreated long house.

Cabot comes in second

This discovery punctured the long-held belief that John Cabot was the first European to reach North America. Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) was born in Italy in 1450, probably in or near Genoa. Like his fellow Genoese, Christopher Columbus, Cabot considered that the best way to get to China and the Spice Islands would be by sailing west, and he became interested in a more northerly route than Columbus. Known to be living in Bristol by 1495, he received a Royal charter from Henry VII to claim any land discovered for England, and was commissioned by the merchants of Bristol. He set sail in a small boat, the Matthew, from Bristol, along with his crew of eighteen. On 24 June 1497, they made landfall on Newfoundland, probably at Cape Bonavista. He reported that ‘the natives of it go about dressed in skins of animals; in their wars they use bows and arrows, lances and darts, and clubs of wood, and slings. This land is very sterile. There are in it many white bears, and very large stags, like horses, and many other animals. And in like manner there are immense quantities of fish — soles, salmon, very large cods, and many other kinds of fish.’ He named the land ‘New Founde Lands’ and by tradition he also named one sheltered harbour St John’s, now the provincial capital, because he first landed on Newfoundland on St John’s Day.

He returned to Bristol, firmly believing that he had discovered a new route to China, and was enthusiastically welcome back to the Royal Court. He was quickly given permission to make another trip, with five boats. He left in spring 1498, but neither he nor his ships returned.

Adrift in the Pacific (#ulink_ddc86099-7ab0-5b2a-9d02-02f298a432ed)

Thor Heyerdahl: The Kon-Tiki man (#ulink_ddc86099-7ab0-5b2a-9d02-02f298a432ed)

“One learns more from listening than speaking. And both the wind and the people who continue to live close to nature still have much to tell us which we cannot hear within university walls.

Thor Heyerdahl

WHEN

1947

ENDEAVOUR

Floating across the empty Pacific Ocean on a raft built using only materials available 1,000 years ago.

HARDSHIPS & DANGERS

Thor Heyerdahl and his crew were putting themselves utterly at the mercy of the capricious Pacific Ocean. They did not know if they would face storms, waves or would simply get lost without a trace.

LEGACY

The voyage of the Kon-Tiki spectacularly proved an anthropological point: that ancient societies could have sailed from South America westwards to colonize the islands of the southern Pacific Ocean.

Thor Heyerdahl (foreground) on Easter Island in 1986.

The story of one of modern history’s greatest achievements in exploration is rooted in a very personal tragedy. Bjarne Kroepelien, a well-to-do wine merchant from Norway, had a lifelong obsession with the islands of the southern Pacific Ocean. He travelled to the area in his twenties and fell in love with the daughter of a Tahitian tribal leader. The pair were married but their union was to end bitterly when Tuimata, his wife, was one of the victims of a Spanish Flu epidemic on the island in 1918. The heartbroken merchant returned to Oslo and the family business. He never again visited Tahiti but his love for the islands, their culture and their people lived on. Over the years Kroepelien amassed the world’s largest collection of Polynesian literature — more than 5,000 books in total.

His collection was to have a remarkable legacy — one that was the change the way anthropologists understood the spread of humankind. Thor Heyerdahl, a zoology student at the University of Oslo, gained access to Kroepelien’s archive and pored over the texts within. These studies led Heyerdahl to a radical theory about how the Polynesian islands were settled. The mainstream academic understanding was that the islands of the south Pacific had been settled by peoples travelling east by sea from Asia. Heyerdahl believed it would also have been possible for settlers to travel west from South America.

Exodus across the Pacific

It was Heyerdahl’s opinion that the famous stone moai statues of Easter Island bore a closer resemblance to the ancient people of South America than to the inhabitants of east Asia. He posited that an Easter Island myth about a battle between two feuding tribes could have been based on actual conflict between settlers from the two continents. Heyerdahl went further, claiming the South American migrants could have travelled further, all the way to the Polynesian islands in the South Pacific.

There was one particularly sizeable and obvious problem with Heyerdahl’s theory; the distance from South America to Easter Island was vast. The remote island was more than 3,700 km (2,300 miles) from Peru, the most likely departure point in Heyerdah’s view. The Polynesian island of Tahiti was a further 4,200 km (2,600 miles) distant. Any journey from the Peruvian coast would have involved months of travel across the Pacific Ocean. Modern maps showed the South Sea Islands as tiny pin pricks in the vastness of the planet’s biggest expanse of open water. Could the ancient travellers have found their way?

A theory that travellers from the east could have settled remote Easter Island inspired the Kon-Tiki expedition.

Putting an idea to the test

Heyerdahl decided there was only one way to find out. Following the end of the Second World War, he started planning his own voyage from the coast of Peru to the islands of Polynesia, using only materials and building techniques which would have been available more than one thousand years earlier. Heyerdahl assembled a crew of five fellow Scandinavians to join him on the journey, each bringing a particular set of skills to the mission. The first to sign up was Herman Watzinger, an engineer who would chart the seas the vessel sailed on and measure meteorological data. Knut Haugland and Torstein Raaby were radio experts who would make and maintain contact with a land-based support crew and any nearby vessels. Bengt Danielsson was the expedition’s ‘fixer’, arranging equipment for the build of the raft and provisions for the team’s time at sea. Erik Hesselberg was a childhood friend of Heyerdahl and, perhaps surprisingly, the only professional sailor chosen for the trip. He served as navigator and later used his artistic skills to create a children’s picture book about the adventure.

Puka-Puka Atoll, the first land sighted by the Kon-Tiki crew since leaving Peru.

The team travelled to Peru and set about their work. As a point of reference, the team turned to hand drawings made by the Spanish Conquistadores, who were among the first Europeans to land in Peru. Their illustrations of the traditional sailing craft used by the indigenous people of the region served as a guide for the Scandinavian team’s raft.

The handmade raft

The team used only materials which could be found locally. Balsa wood, exceptionally light and easy to shape, was used for the main body with strips of pine to provide support. A cabin made of weaved bamboo, 4 m (13 ft) long and 2.5 m (8 ft) wide, would be home for the six sailors during their expedition. The thick leaves of the banana tree were used to roof the cabin and more bamboo was plaited together to form a sail. The mast, nearly 9 m (30 ft) high, was made from sturdy mangrove wood. Rope made from hemp was used to lash the craft together.

The result was a wooden float which may have looked somewhat ramshackle but was, in fact, the result of great care and attention to detail. Over a period of several weeks, the crew had tested various combinations of locally-grown materials before settling on the components which would allow them to create a craft that was large enough to withstand the high ocean but also easy to manoeuvre and repair. The craft was named ‘Kon-Tiki’ an ancient name for the Incan sun-god, and plans were made for a launch in the autumn of 1947.

The Kon-Tiki was well stocked in preparation for a lengthy spell at sea. Canned goods and water containers were provided by the US military. Traditional water-holding containers were also taken so the crew could test their efficiency and usefulness.

‘I jumped on board the raft,’ wrote Heyerdahl in his account of the journey, ‘which looked an utter chaos of banana clusters, fruit baskets, and sacks which had been hurled on board at the very last moment and were to be stowed and made fast.’

The Kon-Tiki, which sailed nearly 7,000 km (4,350 miles) across the Pacific.

Drifting into the endless blue

The mood among the crew was incredibly relaxed given the potentially perilous nature of the journey ahead. In fact, Heyerdahl alone was on board when the Kon-Tiki was pulled out to open sea by a tug boat on 28 April 1947, his fellow sailors being otherwise engaged in last-minute errands.

‘Erik and Bengt came sauntering down to the quay with their arms full of reading matter and odds and ends,’ wrote Heyerdahl. ‘They met the whole stream of people on its way home and were finally stopped at a police barrier by a kindly official who told them there was nothing more to see. Bengt told the officer … that they had not come to see anything they themselves were going with the raft.