По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

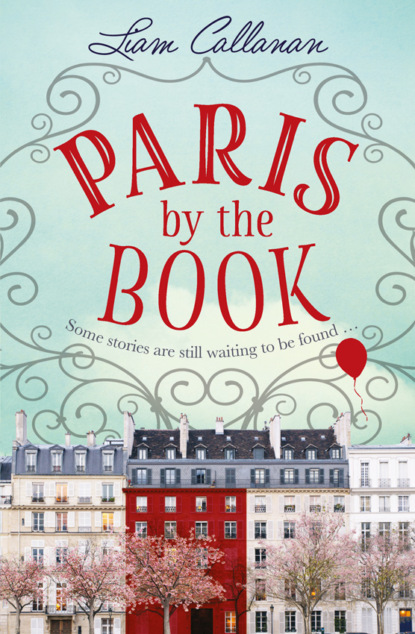

Paris by the Book: One of the most enchanting and uplifting books of 2018

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“It’s some sort of—well, manuscript, I guess,” Eleanor said. “With a cover letter. Addressed to a prize competition. It arrived earlier via campus mail, from the math department. My assistant’s theory is that Robert must have tried to send something to our department’s central printer ages ago—it’s time-stamped March, a month before he vanished—and the document turned left instead of right at some digital intersection, spitting itself out at a random printer across campus.”

“March?” I said. “It’s August.”

“Five months, five hundred yards,” Eleanor said. “That’s about right for campus mail. Speaking of, has my e-mail arrived?”

I tapped the café window; Ellie looked over—as did half the café—and shook her head. “No?” I said.

“Shoot,” she said. I heard clicking. “Resending. In the meantime, let me read just a paragraph or two, because it’s so very . . .”

And here my waking dream began in earnest—or I’d been dreaming since arriving in Paris, or since Robert left.

“Okay. ‘Please find enclosed my submission for the Porlock Prize,’” Eleanor read, and then paused. “Never heard of such a thing. Mind you, I lead a sheltered life. ‘It is’—this is him now—‘per the guidelines, a manuscript that, in the spirit of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s great “Kubla Khan,” lies unfinished due to the author having been interrupted during its production.’ Let’s be clear,” Eleanor said, “Coleridge wasn’t ‘interrupted,’ despite his claim that a ‘person from Porlock’ had ruined his poem; no, he was—well, speaking of brains, actually—”

“Eleanor, Eleanor, I lied,” I lied. “This is an expensive call. And I’ve left the girls on their own in—”

“Shush,” said Eleanor. “The competition, it turns out, is sponsored by a brain surgeon. In Grand Rapids, Michigan. Do you know what’s a telltale sign of a health care system out of control? Neurosurgeons making so much money they endow literary prizes.”

“He’s a neurosurgeon?” I said.

“So says the Internet. Which also says one of the reasons for his starting the contest was that he’d done research on the brain’s ability to handle interruptions.”

“Eleanor—”

“Clever! You interrupted. The man has a point. Okay—let’s see, skimming, another paragraph of throat-clearing, some vague groveling—it’s a little unseemly—it’s also very much Robert, I have to say, but—here ’tis. The synopsis.”

“Eleanor, do we have to do this now? Over the phone?”

“It’s short,” she said.

“So is our time here,” I said.

“That’s my point,” Eleanor said. “The story—Leah, it’s set in Paris.”

Moments before, the humidity had made it seem like there was too much air. Now it felt like there was none.

“I thought so,” Eleanor said, marking my silence. “So here goes: ‘Young Robert and Callie Eady’—yes, he uses real names, or his, anyway; I don’t know what’s up with ‘Callie’; makes me think of Caligula—‘exhausted with their life in Wisconsin’—I’d say that’s overstating things, no?—‘decide to take a year off with their daughters’—no names given—‘and travel the world.’ She’s a novelist, by the way, and he’s a speechwriter—ho, ho! That’s my ‘ho, ho.’ I’ll read on. ‘Once around and then home, much improved, in no small part because the plan is to work their way around the world.’ Okay, and now we get some sheep in New Zealand, grape-picking in Chile, etc., etc., teaching and coaching at a school in Zambia—”

“Eleanor!”

“Yes, yes,” she said. “Anyway, none of that turns out to be crucial. But this is: ‘Their trip stalls’—Robert’s words again—‘almost as soon as it starts. Crossing the Atlantic to France, they fetch up in Paris’—really not sure about that ‘fetch up’—‘where their plans to staff an English-language bookstore fall through. To bide time, they spend days wandering the city, quickly abandoning traditional guidebooks to follow paths laid out by the children’s books and films their two daughters love, chiefly Ludwig Bemelmans’s Madeline books and’— you knew this was coming, didn’t you?—‘Albert Lamorisse’s The Red Balloon.’—Leah, are you listening?”

I was not. Or I was, but not to Eleanor. I was listening to Robert, through words read by Eleanor, trying to make out the words behind the words.

“I admit,” Eleanor said, “it doesn’t sound like him.”

It did and it didn’t. It was true that Robert’s recent experiments had been increasingly esoteric—a term he found “judgmental”—and he had been exploring the creation of electronic texts, including an e-book app wherein a finger swipe not only turned pages but erased words. Academics loved it. Techies, too. And some students, some of them his old fans. In short, lots of people who didn’t spend much money on books. Which was good, because the app was free. A variety of fame resulted. But he no longer seemed much interested in fame, or much else anymore. And I no longer—well, I didn’t understand. I told him so. He tried to explain: So finishing the book will mean—could mean—finishing it off, you know? I did, and excitement briefly flared in me. A large part of me also thought it was nonsense. But we were deep in a difficult season, and I wanted something to celebrate, and nonsense would do. It would be like the old days, our early days, when the less sense an act, a notion, a thought was, the more sense it made. Chase a shoplifter from a bookstore! Marry a man who loved Madeline! Live for art! Make something. And we had. And now we were—erasing that art? That life? Finished, Robert had said, like—

I know, I’d said, and I’d thought I had known, but now—now in Paris, this. This “prize” or contest, which was all about unfinishing? This didn’t sound like him, not the synopsis, not the contest.

Unless—was the whole thing—was this an experimental work of an entirely new order? He’d not only made up a new novel but a competition? Eleanor had found the contest’s website, but maybe Robert, mad puzzler that he was, had generated that, too.

“It’s a lot to take in, I suppose,” Eleanor said. “I think I hear you breathing. I’ll keep going. There’s not too much more. Though—steady yourself. ‘But as the weeks wear on,’ he writes, ‘Paris wears them down, and the family dynamic frays.’ And it would, wouldn’t it? ‘The girls fight. The parents fight. And then, one morning, Robert comes home from a run, and she’s gone.’”

“Wait—who’s gone?” I said.

“You are listening,” Eleanor said. “So, yes, this is the curious part. She’s gone, this Callie character—the wife.”

“The wife?”

“The wife, and stranger still—okay, let me finish.” Eleanor dropped her voice, caught up in the performance. It was almost fun to listen to, to hear someone else get swept away by another’s prose and magic, even if it was only a synopsis. It reminded me that Robert had possessed that magic. It reminded me that it had possessed me once upon a time. It made me realize, briefly, that something similar was happening again, here on a crowded sidewalk in a distant city, my girls behind glass, my husband behind words someone was reading to me. “‘There’s no sign of her,’” Eleanor read. “The wife, he means. ‘There’d been no warning. The police, the embassy, are no help. The father prepares to head home; the children resist. The father’s compromise: a final trip to the bookstore where they were to have worked.’ Whereupon they find a ‘clue.’”

“A clue—Eleanor! All this time you’ve had me on the phone—why didn’t you just—what in god’s name is the clue?”

“It doesn’t say. That’s where it ends. By design, I assume. Indeed, that’s the contest’s conceit. But here’s what I think of as a clue: the synopsis and manuscript differ. I’m not sure why, and this is only after the speediest of reads, but it appears Robert changed the manuscript before writing the cover letter. Or maybe after. What I mean is, in the manuscript, there’s just this one material change: it’s no longer Callie, the wife, who leaves. It’s . . .”

She paused.

“Well, it’s the husband,” she said. “I don’t know if that’s a clue or the opposite of one. But otherwise, for all this talk of clues in the cover letter, there’s no explicit discussion of clues in the manuscript itself. Maybe he forgot. More likely, as I said, things changed. We don’t even know if he sent it in, after all—perhaps this was just a rough draft.”

We didn’t know anything, she said, but I knew this: it sounded like Eleanor was gloating. She’d had a hunch that Robert was alive and well somewhere, and this somehow proved that.

But it didn’t. We’d found my husband’s manuscript. Not my husband. This manuscript wasn’t evidence he was alive. Unfinished, it was evidence he was dead.

Wasn’t it?

Eleanor could endure my silence no further. “Oh, but of course,” Eleanor said, thinking she’d figured out why I’d paused. “I have anticipated your very desire. My able assistant has already scanned in the whole thing, cover letter and all. And she e-mailed it to you along with Daphne’s passport page. Maybe that’s why it took so long. No matter—Ellie messaged me while we were talking, said she’d gotten it, was printing it.”

“Ellie? Eleanor, you should have . . .” I turned to look through the glass again. Ellie’s workstation was empty. I looked at the line for the bathroom; no.

And then I saw my two daughters, sitting at a little round table, Daphne bent over Ellie bent over a messy pile of pages—bent, anyway, until Ellie looked up, saw me looking at her, and opened her mouth.

I opened mine, too, but nothing came out. My grief books were no help here; none of them discussed partial manuscripts that churned out of printers in Paris. What could I tell my girls that they would believe now? Their father wasn’t gone, he’d come back? Or their father had come back and gone again? Or their father, my husband, was sitting right there on the table, just beneath those words, staring out at us? I wanted to go in and stuff the pages back into the printer. I wanted to gather them up in one giant, messy pile and hug them to me, and not let go: I’m sorry I thought you were dead! I’m sorry you ran away. I’m sorry I said I would—

And then I looked around, and the pages became pages again, and my girls became fatherless again, and I thought, I’m sorry I thought you were back.

Here is my own synopsis of what happened next, pared to the minimum and thus truer than Robert’s: pay, taxi, room, read, argue, cry, call, embassy, cry, call, read, argue, argue, call, call. Stay.

Stay?

Stay in Paris. The girls’ idea. Or, Eleanor later argued, their father’s.

I had not read anything of Robert’s in manuscript form in quite a long time. (I’d once made the mistake of reading a manuscript of his in bed and falling asleep—a perfectly common event in any reader’s life, but, as I learned, unacceptable for an author’s wife.) His words, once bound into a book, always seemed settled, set.

Reading him in double-spaced, 12-point Times Roman was an entirely different experience, and not just because he fussily preferred throwback typewriter fonts: the words here seemed jittery, loose, like a photograph in a tray of developer that refuses to fix.

The manuscript wasn’t bad; I’ll get that out of the way immediately. It didn’t sound like him, but then, none of his books for adults—and this was one—really did. But I hardly focused on that, so distracted was I by the fact that he’d written something. He’d gone away, and come back waving pages!

And on those pages, a message. To us. This was the girls’ opinion, and one they held fast to, despite the cover letter to the prize competition. The book was a message and the message was this: go to Paris, stay in Paris. (Come to think, that may be the synopsis for every book ever set in Paris, even the ones—and there are many, even a majority—about leaving.)