По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

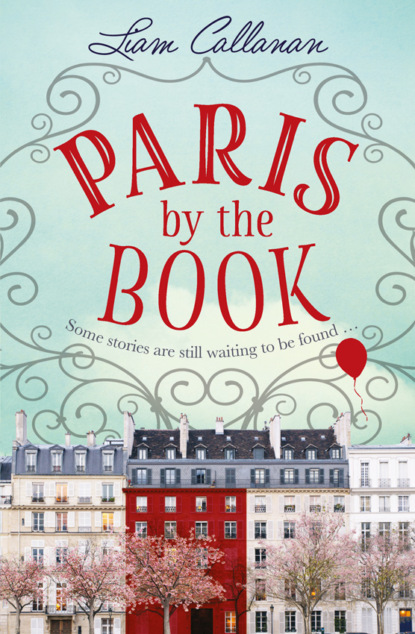

Paris by the Book: One of the most enchanting and uplifting books of 2018

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

We sell books. Gold letters say this on the window. bookshop to one side, librairie anglophone to the other. In the middle, our name, a debate. It had been named for the street, which is named for Saint Lucy. This confuses people; across town, there is another street named for her. More confusion: Lucy is the patron saint of writers, but Madame Brouillard said the name sometimes brought in religious shoppers, and most times, no one at all. Once upon a time, she insisted to me, the street had been crowded, not just with book buyers but booksellers. One by one, the stores departed, and many left their stock behind with Madame. The English-language volumes, not the French. The dross, not the treasures. And needless to say, the dead, not the living. She had hardly anything by living authors.

I suggested rechristening the store The Late Edition. Late as in we would henceforth specialize in authors who, unlike their books, were dead.

She didn’t like it, but she let me proceed, as one of her keenest pleasures is bearing a grudge. I sometimes think it’s why she let me, who knew little about bookstores (and even less about French), assume control of a bookshop she’d owned for decades. And it’s likely why she watched with interest as the dead-authors angle turned out to be just the sort of Paris quirk travel writers craved (who are quick to note that I make living-authors exceptions for children’s books and books of any sort by women).

Madame pays Laurent off the books to bring more stock from storage units outside Paris, where she’s piled the leavings of her predecessors. Laurent says there aren’t enough customers in the world for all the books waiting there.

And Madame had a very small share of the world’s customers. When we took over the store, the running joke was that we were down to three. Two Americans and one New Zealander, who also formed the sum total of my friends in Paris: another joke. And whenever my daughters made it, I would smile to hide the hurt. Not only was it a stretch to call the three “customers,” but even more so to call them friends. Still, I was grateful they occasionally bought books.

The truth is, in modern France as in modern elsewhere, Amazon sells books (and snow tires); bookstores sell coffee. Or, the profitable ones do. Those with bookstores that only sell books have a tougher time. It is slightly easier in France, although Amazon’s smirk is almost as ubiquitous here as it likely still is in Milwaukee, where my girls and I lived until recently. (Unless two years is not recent? Some days it feels like twenty years. Other days, twenty minutes.) Enlightened France, however, regulates discounting books (or attempts to) and, even more cheering, occasionally provides independent bookstores financial support. Such aid favors the selling of new books, but Madame Brouillard had long ago figured out a way to benefit, by running a second, smaller bookstore that sold new titles in French. It just happened to coexist inside a bookstore that sold used books in English. The French store specialized in children’s titles and was in the front half of what looks like the building’s second floor but is actually a cramped mezzanine.

The back half of the mezzanine, flimsily walled off, became my daughters’ bedroom, which, if they left the door open upon leaving, sometimes became an ersatz English-language children’s bookstore: Daphne once complained someone was stealing her old Beverly Cleary books. I’d been selling them without asking buyers just where they’d picked them up.

The kitchen, living area, and my bedroom are on the floor above the girls. With higher ceilings and more elaborate architectural detail, this is the étage noble. But in our building, the resident noble, Madame Brouillard, commands the top two floors, which have much better light. She lives on one and her own private collection of books lives just above, or so she once told me. For the longest time, I’d never ventured farther into her apartment than the small sitting room just inside the door (which, like the building, like so much of Paris, looks just like authors and artists have long led you to think: late-sun yellow, delicate furniture, lace, an old crystal lamp atop a tiny table).

Paris, in other words, like Madame’s promises to show me the top floor, is a challenge, an invitation, a city that doesn’t distinguish between the two. It may be why my conversations with Madame often ended abruptly. Or it was because she knew, long before I did, that the trap I’d set was not for customers but for my vanished husband—and that it had ensnared me instead.

It is faintly ironic I find myself running a bookstore, because almost twenty years ago I was caught running from one, a stolen item in hand. And ironic that I’ve ever chased any man anywhere in Paris, because on that long-ago night, my husband was chasing me.

Please change the set. Unroll a new sidewalk, erect a different storefront, lower a fresh backdrop. Gone is the Eiffel Tower, and arriving in its place is—nothing, really. Blue skies, clouds if you like. A simple city skyline. Steeples here and there, some smokestacks, but otherwise, clip-art buildings. After all, we’re no longer in Paris, but Milwaukee.

And there, on my left hand, no ring. We’re not married yet, my husband and I. Two moon-pale Midwesterners, we don’t even know each other, which makes it awkward that he’s just accosted me on the street—a series of heys! dopplering ever closer until I had to turn—about something I have clutched in my right hand. A book. I’m not hiding it, mind you. (I’m not hiding it because I couldn’t—it was about ten by twelve inches, a children’s book, with a bright red balloon on the cover.)

“Hi,” he said with half a smile. “I think you forgot to pay?” He now crinkled half his face to go with his half smile, which was good. It gave him some creases, which gave him some years. He was short, fair, slender but athletic. I’d taken him for seventeen. On his high school’s cross-country team. Now I added four years. Later he would add four more: twenty-five. Incredible.

“Oh, I pay,” I said. “I pay every day.” I got ready to rant about men accosting me on the sidewalk, about men everywhere accosting women everywhere on all the sidewalks of the world—but it wasn’t true, not for me, not there, not then.

What was true was that I was embarrassed. Embarrassed I’d stolen something—I’d never stolen anything before—and embarrassed that I’d stolen a children’s book. And I was embarrassed I was so poor. I was almost twenty-four, and I had exactly that many dollars in my checking account. I would have more on Monday when I received my grad student stipend, but until then, I had twenty-four dollars, two suspended credit cards, and a surplus of anger. The university library had inexplicably closed early, and I’d decided that I needed the book version of Albert Lamorisse’s 1956 movie, The Red Balloon, at that very moment to finish my master’s thesis on the great (and quite curious) man. Never mind that I knew by heart every frame of this classic Paris film and every page of the companion book—indeed, its every cobblestone and cat (one living, black, another on a building’s poster, white).

Many people my age briefly shared my obsession as kids, thanks to rainy-day recess copies of the film that saturated American elementary schools in the 1970s and ’80s. I noticed that, as years passed, those children moved on. I knew I had not, and would not. That book was my first love. Like a crush, a companion, a boyfriend of the type I wouldn’t really have, ever. That book, that film, understood me. Or so I felt. I knew that I understood it. And moreover, I understood its Paris. For other girls (and the odd boy), Paris meant flowers and romance and accordions wheezing. The Red Balloon has none of this. It’s beautiful, but bracing. Some find it sweet, but I didn’t like sweet things as a child and I don’t much now. I’m surprised more people—like the staff of the Milwaukee bookstore I was stealing from—don’t realize the obvious. Red is the color of warning.

I wish I myself had paid more attention to that warning. I was in grad school then for film studies—film criticism—but had started in filmmaking, because I did want to make something, and Lamorisse made it look so easy. It wasn’t, especially when I discovered my filmmaking program disdained narrative. How much better The Red Balloon would have been, they said, had it been solely that: a close-up of a balloon for thirty minutes—or thirty hours! No dialogue. No actors. Just balloon. What do you think, Leah? I thought I’d transfer to film studies, and did. There they told me I needed to be interested in films other than The Red Balloon and cityscapes other than Paris. For a while, I let them think I was. But I couldn’t sustain the fiction; in a very short time, I would burn out, give up. Or as I liked to think of it, give in, and to a private truth: I was mostly still interested in making my own film. I didn’t know how, when, or what it would be. I did know where it would take place: far from Wisconsin.

And far away from this boy accosting me on the street outside a bookstore.

I ran.

Doc Martens do not make for good running shoes, especially when purchased at Goodwill, a size and a half too big. I worried my pursuer might think I’d stolen them, too. I worried that I was worried what he would think.

When he finally caught up to me, the first words out of his mouth were two I myself was about to say.

“I’m sorry?”

He was beautiful. I know there’s a delicacy about the word. There was a delicacy about him.

“It’s okay,” I said, neatly absolving him for something that I had done.

He’d been in line at the cashier when he’d seen me slip the book out of the store. He’d told them to add it to his bill, impulse-bought still another book, and then he’d chased me. “Take it,” he said now, though I already had.

“I’m not sure I want it anymore,” I said, looking at it, lying.

“Can I—can I buy you a coffee?”

“How about a beer,” I said, “unless you’re worried I’d steal that, too.”

He wasn’t, or maybe he was, because he kept a grip on his glass at the bar when we met later that night. He was nervous or thirsty or knew this about himself: his hands, if left unoccupied, would flutter, rise, fall, paint shapes familiar and not. He’d run a hand through his hair and nod, or rub his face and frown, or draw a letter on the table, another in the air. It was how he spoke. It was how he smiled. It was nerves, yes, but of a generalized sort, at least at that point, and my goal soon became to have him be nervous about me. I wanted to see, and feel, what those hands could do.

And he had these eyes. Gray, but the right iris was stained with a tiny burnt-orange splotch I felt compelled to comment on.

He briefly closed his eyes in reply. “It’s meaningless,” he said, “in humans. But in pigeons? Eyes? A big deal, especially if you race them, which I don’t, but it’s how you tell them apart, how you know which one’s yours.”

And at that moment, I did.

“So, Paris?” he said, now tapping The Red Balloon, which lay on the table between us. I winced, I think invisibly. Tap, tap: it felt like little thumps to my chest.

Robert explained that his own favorite children’s stories were by Ludwig Bemelmans. The Madeline series.

In an old house in Paris

That was covered with vines

Lived twelve little girls

In two straight lines. . . .

I shook my head. Once upon a time—first or second grade—those would have been, had been, fighting words. The hats, the bows, the uniforms? The two straight lines?

But on my future husband plowed. He thought I should be, had to be, a Bemelmans fan, given my interest in Lamorisse: “both artists, before—and after—anything else!” In his hands appeared a copy of the first Madeline book. Which he had purchased for me. To go with the book I’d stolen.

He slid Madeline alongside The Red Balloon, both books flat on the tiny table between us. I looked down at the covers and then around at the bar.

“Everyone is definitely jealous of the date I’m on,” I said.

Untrue. But I was definitely anxious. I was protective of my passion, my Paris. So much so, I’d long put off going. Poverty had helped me stall, but so had a cynical certainty that the Paris I’d find would disappoint. It wouldn’t be the 1950s Paris of The Red Balloon. It wouldn’t be as rhapsodically bleak. The balloon, if I found one, if one found me, would pop long before I reached the final page.

(There are many ways to describe cowardice. This is one.)

“The way I see it,” he said, continuing as if I’d not spoken, “and I didn’t see it until just now, actually, looking at the books side by side: it’s weird, isn’t it?”

He was weird, of course, and that only slew me more. In grad school, the default was that the default did not make sense. Our lives were dispiriting, impoverishing, and largely nocturnal, so we thrilled to what illuminations there were, even if they flickered in strange ways. Especially if they did. I looked at him, carefully. He looked at the books.

“It’s two different ways of looking at the world,” he went on. “One city—”

“I don’t buy that,” I said, though I did like a good fight.

“You’re either a Madeline person or a Red Balloon person,” he said. (I didn’t buy this then either, but genetics bears him out: both our daughters would have his eyes and preference for Bemelmans.) “Paintings, or photographs. Paris in color, or black and white.”

“The Red Balloon is in color. It’s all about color.”