По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

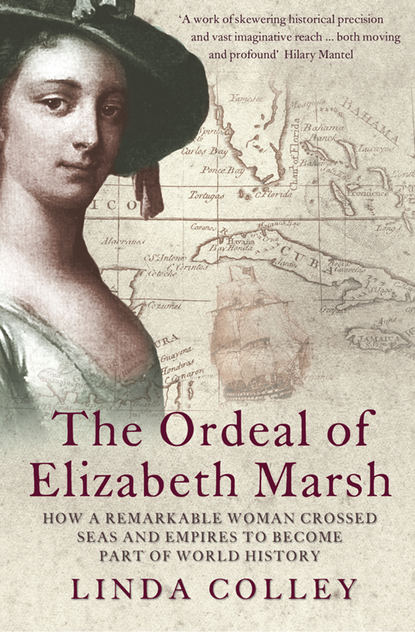

The Ordeal of Elizabeth Marsh: How a Remarkable Woman Crossed Seas and Empires to Become Part of World History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#litres_trial_promo) Yet to view him simply as a manual labourer would be quite wrong. Thomas Rowlandson’s sensitive study of a ship’s carpenter was made more than a decade after Milbourne’s death, but the tools the artist gives his figure – an adze in one hand and a drawing instrument in the other – accurately convey the occupation’s composite quality. As suggested by the adze (an axe with a curved blade), it involved hard physical effort. Timber had to be cut to size, a ship’s rotten wood and any cannon shot embedded in it cut out and made good. As indicated by the drawing instrument, however, this was only part of the job. Milbourne was fully literate, and he had to be. A ship’s carpenter was expected to write ‘an exact and particular account’ of his vessel’s condition and propose solutions to any defects. He needed to know basic accounting so as to estimate the cost of repairs, and keep check of his stocks of timber and other stores. And he required mathematical and geometrical skills: enough to draw plans, calculate the height of a mast from the deck, and estimate the weight of anchors and what thickness of timber was required to support them.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Looked at this way, it becomes easier to understand why the foremost English shipwright of the late seventeenth century, Anthony Deane (c.1638–1720), was knighted and made a Fellow of the Royal Society. Because of increased transoceanic trade, expanding empire, the growth of European and of some non-European fighting navies, and recurrent warfare, skills of the sort that Milbourne Marsh commanded were in urgent national and international demand. Not for nothing do we refer today to ‘navigating’ and ‘surfing’ the web. Rather like cyberspace now, the sea in Milbourne Marsh’s time was the vital gateway to a more interconnected world. Consequently, those in possession of the more specialist maritime skills were in a position to rise economically, and often socially as well. ‘The Ship-Carpenter … to become master of his business must learn the theory as well as practice,’ Britain’s most widely read trade directory insisted in 1747: ‘it is a business that one seldom wants bread in, either at home or abroad.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The nature of her father’s occupation was of central importance in Elizabeth Marsh’s life. At one level, and along with her many other seafaring relations, Milbourne Marsh gave her access to one of the few eighteenth-century organizations genuinely possessed of something approaching global reach: the Royal Navy. This proved vital to her ability to travel. Long-distance oceanic journeying was expensive, but over the years Elizabeth’s family connections repeatedly secured her free or cheap passage on various navy vessels. She also gained, by way of these maritime menfolk, a network of contacts that stretched across oceans: in effect two extended families, her own, and the navy itself. ‘A visit from Mr. Panton, the 1st Lieutenant of the Salisbury,’ she would record while sailing off the eastern coast of the Indian subcontinent in 1775: ‘he seemed well acquainted with most of my family.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

But her father’s occupation also impacted on her in less enabling ways. It is conceivable that she grew up aware that her mother was different in some manner, or looked at askance by her relations. She certainly seems to have been perpetually insecure about her own and her family’s social position. Milbourne Marsh was from a self-regarding maritime dynasty that encouraged ambition, and he was a master craftsman in a global trade; but his was still an interstitial, sometimes vulnerable existence, lived out between the land and the sea, and between the labouring masses on the one hand, and the officer class on the other. Some of the tensions that could ensue can be seen in two crises that threatened for a while to engulf them all.

In April 1741, six of Milbourne’s workmen in Portsmouth dockyard sent a letter to its Commissioner accusing the carpenter of embezzlement. He had kept back new beds and bedding intended for his current ship, the Cambridge, his accusers claimed, and arranged for them to be smuggled out of the yard at midday, ‘when all the people belonging thereto are absent’. He had used naval timber to make window shutters, chimneypieces, and even palisades. Milbourne’s joiner reported that he had seen ‘the outlines of the head of one [a palisade] drew with a black lead pencil on a small piece of board’ on his desk, ‘which he verily believes was intended for a pattern or mould’. Another of Milbourne’s accusers told of being ordered to chop up good oak for firewood, and how he had carried the sticks out of the dockyard to the Marsh family’s lodgings in the New Buildings, where the carpenter ‘was in company the whole time’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Charges of embezzlement, if proved, normally brought instant dismissal from a navy dockyard. Milbourne Marsh retained his post and livelihood not because his excuses convinced (they were judged ‘indifferent’), but because his superiors recognized his ability (‘the carpenter bears the character of a good officer’). It is the private man and the family’s lifestyle, though, which emerge most sharply from this incident. The workmen’s resentment at Milbourne’s efforts to add some distinction and ornament to his family’s stark lodgings (and perhaps also to make extra money from selling illicitly-constructed window shutters, etc.), like their scorn for his small attempts at a social life (‘in company the whole time’), and their determination to inform against him in the first place are suggestive. These things point to a man and a family visibly getting above themselves and their surroundings, experiencing industrious revolution, and consequently arousing envy. Milbourne’s shuddering answer to his workmen’s accusations confirms this, while also showing how entangled he necessarily still was in deference:

Honourable Sir the whole being a premeditated thing to do me prejudice, for my using of them ill (as they term it) in making them do their duty. Hope you look on it as such, as will appear by my former behaviour and time to come.

(#litres_trial_promo)

He was literate enough to know how to use the word ‘premeditated’, but his syntax was not, could not be, that of a formally educated man, and he was naturally terrified of dismissal. Even more revealing is his explanation of why exactly he had defied regulations and commandeered the navy’s bedding:

My wife having been sick on board [the Cambridge] for five weeks, and no probability of getting her ashore, [I] thought it not fit to lie on my bed till I had got it washed & well cleaned, so got the above bedding to lie on till my own was fit.

(#litres_trial_promo)

So it was not just Milbourne Marsh who was amphibious, dividing his time between the sea and the land. His wife, and therefore presumably their five-year-old daughter also, were caught up in this way of living too. Already, Elizabeth Marsh was travelling.

Milbourne’s wife and child – soon children – were also caught up in fears for his survival, and therefore for their own. He fought in only one sea battle during his career, but it was a major one. In 1742 he was sent to the Mediterranean. Based first on the Marlborough and then on the Namur, a ninety-gun second rate and the flagship of Admiral Thomas Mathews, Milbourne Marsh also worked on the thirty-odd other warships in Britain’s Mediterranean fleet, dealing with day-to-day repairs as they waited for the combined Franco-Spanish fleet to emerge from Toulon, France’s premier naval base, and fight.

(#litres_trial_promo) It is not clear whether any of his family accompanied him, or if they waited throughout in Portsmouth, or London, or with his parents who were now in Chatham, Kent. What is known, because Milbourne Marsh later gave evidence to a naval court martial, is that on 11 February 1744, for the first and only time in his life, he saw action.

‘I can tell you, exactly to a minute, the time we fired the first gun,’ he would tell the court, for ‘… I immediately whip’d my watch out of my pocket, and it was then 10 minutes after one o’clock to a moment.’ The enemy vessel that the 780-man crew of the Namur engaged was the Real, the 114-gun Spanish flagship and part of a twenty-seven-ship Franco-Spanish fleet. Initially, Milbourne the specialist was allowed to experience the battle below deck. Once the Namur started sustaining damage, however, his skills drove him above: ‘The Admiral sent for me up, and ordered me to see what was the matter with the mizzen topmast’ – that is, the mast nearest the ship’s stern. He had to climb it, and then the main mast, under fire throughout, for the Real was only ‘a pistol-shot’ away from them. Milbourne’s breathless account of what happened next is misted by nautical phraseology, but conveys something of what it was like to clamber across the rigging of a sailing ship under fire, and how difficult it was to make sense of a sea battle as it was happening:

At the same time I acquainted the Admiral of the main top mast, I was told, but by whom I can’t tell, that the starboard main yard arm was shot. I looked up, and saw it, from the quarter deck; I went to go up the starboard shrouds to view it; I found several of the shrouds were shot, which made me quit that side, and I went up on the larboard side, and went across the main yard in the slings, out to the yard arm, and I found just within the lift block on the under side, a shot had grazed a slant … when I went down, I did not immediately acquaint the Admiral with that, for by that time I had got upon the gangway, I was told that the bowsprit was shot, and immediately that the fore top mast was shot.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In strategic and naval terms, the Battle of Toulon proved an embarrassment for the British. For reasons that provoked furious controversy at the time and are still debated now, many of the Royal Navy ships present did not engage. The damage to the Namur’s masts and rigging, which Milbourne tried so desperately to monitor, persuaded Admiral Mathews to withdraw early from the fighting on 11 February, and he retreated to Italy two days later. The Franco-Spanish fleet was forced back to Toulon, but emerged from the encounter substantially intact. Milbourne Marsh’s own account of the battle underlines again some of the paradoxes of his work. His testimony makes clear that he was obliged to possess a pocket watch, still a rare accessory at this time among men who worked with their hands. It is also striking how confidently this skilled artisan communicated with the Admiral of Britain’s Mediterranean fleet. Indeed, when Mathews was court martialled for failing at Toulon, he asked Milbourne to testify on his behalf. Yet what happened in the battle also confirms the precariousness of the carpenter’s existence, and therefore of his family’s existence.

At one stage, the Namur’s withdrawal left the Marlborough, Milbourne Marsh’s former ship on which many of his friends were still serving, alone to face enemy fire. He watched, from relative safety, as the sails of the Marlborough caught fire, and as its main mast, battered by shot, crashed onto its decks. The ship stayed afloat, but its captain and about eighty of its crew were killed outright, and 120 more of its men were wounded. The battle also killed the Namur’s Post-Captain, John Russel, who had been one of Milbourne’s own patrons, along with at least twenty-five more of the ship’s crew. As for the Spanish, a British fireship had smashed into some of their warships, resulting, it was reported at the time, in ‘the immediate dissolution of 1350 souls’. Witnessing death on this scale, experiencing battle, persuaded Milbourne to change course. He was not a coward: one of his private discoveries at Toulon was that, at the time, he ‘did not think of the danger’.

(#litres_trial_promo) But he was now in his thirties, married, a father, and his parents’ oldest surviving son, whereas most seamen were under twenty-five and single. So in 1744 Milbourne Marsh left the sea. For the next ten years he repaired ships at Portsmouth and Chatham dockyards. On land, at what passed for home.

For his daughter, Elizabeth Marsh, this decision led to a more stationary, and seemingly more ordinary, life. To be sure, there were certain respects in which her experiences in the 1740s and early ’50s already made her distinctive. Moving between Portsmouth, London and Chatham, and between various ships at sea and the land, allowed her in some respects an ironic counterfeit of genteel female education, but also more. In addition to the fluent French she acquired from aunt Mary and uncle Duval, she learnt arithmetic and basic accounting from her father, and she acquired a relish for some of the more innocuous pastimes common among sailors, reading, music and singing. She learnt too how to operate without embarrassment in overwhelmingly masculine environments, and how to tolerate physical hardship; and she also learnt, through living close to it, and through sailing on it from infancy, how not to fear the sea, or to regard it as extraordinary, but rather to take travelling on it for granted. She also learnt restlessness and insecurity, and – from watching her mother – a certain female self-reliance.

Mariners’ wives had to be capable of a more than usual measure of independence and responsibility, because their husbands were so often away. During Milbourne’s absences at sea, Elizabeth Marsh senior ran their household in the New Buildings and its finances by herself.

(#litres_trial_promo) She also had to cope at intervals with the harshness and enforced intimacies of living aboard ship. Both of their sons, Francis Milbourne Marsh and John Marsh, the latter Elizabeth Marsh’s favourite and confidant, seem to have been born at sea. Giving birth to the elder, Francis, may indeed have been what confined Elizabeth Marsh senior to the Cambridge in Portsmouth harbour – that is, several miles from shore – for several weeks in 1741, and what tempted Milbourne to ‘borrow’ supplies of navy bedding ‘till my own was fit’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In the normal course of events, none of these mixed influences on their daughter Elizabeth Marsh would have mattered very much. When her father left the sea in 1744 after the Battle of Toulon, his and the family’s prospects were modest, and would have appeared predictable. One of the attractions of working in naval dockyards, as distinct from a commercial shipyard that paid higher wages, was that they allowed skilled employees a job for life. Once he came ashore in 1744, Milbourne’s income declined slightly, from £50 per annum to around £40, a sum that placed the family at the bottom of England’s middling sort at this time, ‘the upper station of low life’, as Daniel Defoe styled it.

(#litres_trial_promo) But at least there was security. It seemed likely that Milbourne would build and repair a succession of warships until he was pensioned off, that his two sons would in due course become shipwrights in their turn, and that ultimately his only daughter would marry a man of the same trade. But this was to reckon without changes that crossed continents, and the second influential man in Elizabeth Marsh’s life: her uncle George Marsh.

Born in January 1723, George Marsh was the eighth and penultimate child of George Marsh senior and Elizabeth Milbourne. This position in a large artisanal family may have made him slighter in physique, and more susceptible to illness – he seems to have suffered sporadically from epilepsy – but he was as driven as any eldest child. Initially sent to sea in 1735, because his father was not ‘able to purchase me a clerkship’, he soon moved to an apprenticeship to a petty officer in Chatham dockyard, and by 1744 was working as a clerk for the Commissioner of Deptford’s naval dockyard.

(#litres_trial_promo) His next break came almost immediately. In October 1745 the House of Commons demanded a detailed report on how naval expenditure in the previous five years, when Britain had been at war with Spain, compared with that in the first five years of the War of Spanish Succession (1702–07). As he was ‘acquainted with the business of the dockyards, and no clerk of the Navy Office was’, George Marsh was ‘chosen … to perform that great work’. Labouring at the Navy Office in London ‘from 5 or 6 o’clock in the morning till 8 or 9 o’clock at night from October to the end of January’, mining a vast, unsorted store of records for the requisite figures, and organizing and writing up the usable data, exacerbated his epilepsy. He suffered intermittent attacks of near-blindness and dizziness, and ‘fell several times in the street’, he recorded much later, ‘and therefore found it necessary to carry constantly in my pocket a memorandum who I was and where I lodged’. He nonetheless produced the report ‘in a few months’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

This episode suggests some of George Marsh’s qualities: his ferocious capacity for industry, strong ambition, and utter belief in paperwork. It also suggests how – through him – Elizabeth Marsh was connected to yet another aspect of modernity and change. The circumstances of her birth and upbringing had already linked her with slavery, migration, empire, economic and industrious revolutions, the navy and the sea. But it was primarily through her uncle George Marsh that she connected with the expanding power of the British state at this time, and with an ever more conscious mobilization of knowledge and paperwork in order to expand that power. To paraphrase the economist J.R. McCulloch’s later verdict on the East India Company, Elizabeth’s father, Milbourne Marsh, was caught up with the power of the sword, Britain’s fighting navy; but it was her uncle, George Marsh, who exemplified the power of the pen and the ledger.

(#litres_trial_promo)

And he was unstoppable. He rose early every morning, drank only water, confined himself to two meals a day, took regular exercise, spent little on himself, and worked very hard. In 1750 he moved from the provinces to the tall pedimented brick building that Christopher Wren had designed for the Navy Office in Crutched Friars by the Tower of London. From 1751 to 1763, George Marsh was the Clerk in charge of seamen’s wages. He then spent almost ten years as Commissioner of Victualling, before becoming Clerk of the Acts in 1773. This was the position that Samuel Pepys had occupied after 1660, and used as a power base from which to transform the administration of the Royal Navy. Pepys, however, had been able to draw on aristocratic relations and on high, creative intelligence. George Marsh possessed neither advantage, yet he retained the Clerkship of the Acts for over twenty years, and ended his career as a Commissioner of the Navy. At his death in 1800, this shipwright’s son was worth by his own estimate £34,575, over £3 million in present-day values.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The contrast between his remarkable career and his evident personal limitations reduced some who worked and competed with him to uncomprehending fury. George Marsh, complained his own Chief Clerk in 1782, was

totally unfit for the employment as he can neither read, spell, nor write. This office has in my memory been filled with ability and dignity … but the present Clerk of the Acts has neither, and we should do ten times better without him, for he only perplexes matters.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Yet, as this denunciation suggests, some of the criticism George Marsh attracted at different stages in his career was rooted in snobbery, and he was always able to exploit people’s tendency to underestimate him. In reality, he wrote all the time, privately, and not just in his public capacity. His papers also confirm that he read widely and that, like his parents and his niece Elizabeth Marsh, he enjoyed constructing stories. More than any other member of his immediate family, perhaps because he spent virtually all of his life in a single country, George Marsh seems to have been conscious of the scale of the transformations through which he was living, and he sought out different ways to make sense of them. He was the one who stayed behind. He was the spectator, the recorder, the collector of memories and eloquent, emblematic mementoes. Most of all, George Marsh was someone who relished facts and information, and knew how to deploy them: ‘I am sensible my abilities fall far short of some other men’s,’ he wrote towards the end of his life, ‘but [I] am very certain no one knows the whole business of the civil department of the Navy better or perhaps so well as I do.’

(#litres_trial_promo) This massive, cumulative knowledge gave him an element of power, as did his acute understanding of how patronage worked.

As his correspondence with successive aristocratic First Lords of the Admiralty reveals, he was both unctuously deferential in his dealings with his official and social superiors, and capable sometimes of hoodwinking them. In private, and like his parents, George Marsh tended to be critical of members of the aristocracy, writing regularly about the superiority of ‘the middle station of life’, and of those (like himself) who had to work seriously hard for a living. But he was adept at the patronage game, which necessarily involved him paying court at times to ‘the indolent unhappy nobility’, and he was interested in securing advancement and favours for more than just himself. He ‘always had a very great pleasure’, he wrote, in ‘doing my utmost to make all those happy, by every friendly act, who I have known to be worthy’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Chief among these worthy beneficiaries were the members of his own family. It was George Marsh’s willingness and ability to use his power and connections to promote his family that transformed Elizabeth Marsh’s expectations, and that separated her forever from the life-trajectory that might have been anticipated for a shipwright’s daughter. Having as her uncle someone with access to influence over several decades was one of the factors that made her life extraordinary. By way of George Marsh, she was able at times to have contact with some of the most powerful men in the British state, while also being helped to travel far beyond it.

His first substantial intervention in his niece’s life was indirect, but it changed everything. In January 1755, using his connections at the Navy Board, George Marsh secured for Milbourne Marsh the position of Naval Officer at Port Mahón in Menorca.

(#litres_trial_promo) A ‘Naval Officer’ in eighteenth-century British parlance was not a fighting sea officer. The post was a clerical and administrative one, in an overseas dockyard, and for a ship’s carpenter it represented a distinctly unusual career break. To begin with, it tripled the family’s income. In the late 1740s and early ’50s, Milbourne had rarely earned more than £12 a quarter, whereas this new post brought with it an annual salary of £150, and the opportunity to make more.

The rise in income was only part of the alteration in the family’s status and outlook. As a carpenter aboard ship, Milbourne had been an uneasy amalgam of specialist craftsman, resident expert and manual labourer. This now changed. Nothing would ever take him completely from the sea, or from his delight in the construction of wooden ships and in drawing plans, but from now on he ceased to work with his hands for much of the time. The announcements of his promotion in the London press referred to him as ‘Milbourne Marsh Esq.’, thereby conceding to him the suffix that was the minimum requirement for being accounted a gentleman.

(#litres_trial_promo)

But the most dramatic change involved in his promotion to Naval Officer was one that affected his whole family, his wife, their sons, and – as it turned out – the nineteen-year-old Elizabeth Marsh most of all. In March 1755, the family left Portsmouth forever and sailed to the Mediterranean and Menorca. She was on her way.

2 Taken to Africa, Encountering Islam (#ulink_d1e012cb-8f8c-5126-a0de-6249b0ea8a3b)