По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

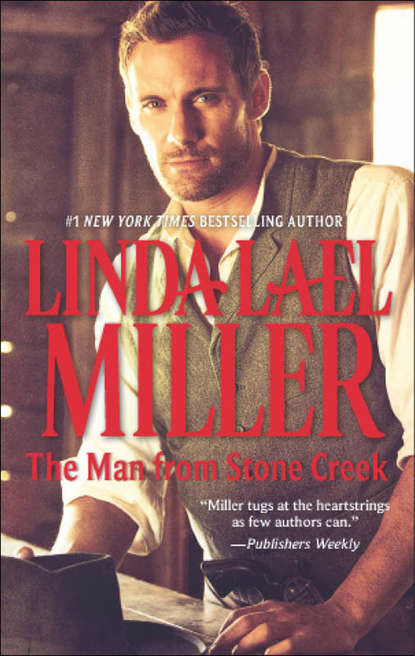

The Man from Stone Creek

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“They used dynamite to cause an avalanche,” Vierra explained, lingering at the place marked as Reoso Canyon. “The train, of course, was forced to stop. They took a shipment of gold, and the wife and young daughter of a patron were captured, as well. The wife was found later—” Vierra stopped, and his throat worked. “She had been raped and dragged to death behind a horse. There has been no word of the girl.”

“Christ,” Sam rasped, closing his eyes for a moment.

Vierra was silent for a long time. When he spoke, his voice was flat. “I was told that you would give me a map corresponding to this one. Showing all the places this gang has struck on your side of the border.”

Sam nodded, reached into the inside pocket of his coat and handed over a careful copy of the drawing the major had given him. “Except for the woman and the girl,” he said as Vierra unfolded the paper to examine it in a shaft of moonlight, “it’s a version of what you just showed me. Rustling. Train robberies. They cleaned out a couple of banks, too, and killed a freight wagon driver.”

“Our superiors,” Vierra observed, his gaze fixed on Sam’s map, “they believe we are dealing with the same band of men. Do you know why?”

Sam knew it wasn’t a question. It was a prompt. “Yes,” he said after a moment of hesitation. “They leave a mark.”

Vierra folded Sam’s map carefully and tucked it away inside his vest. “A stake, driven into the ground, always with a bit of blood-soaked cloth attached.”

Bile rose in the back of Sam’s throat. He’d seen the signature several times, and just the recollection of it turned his stomach. He nodded, took another moment before he spoke. “I suppose you’ve considered that it might be the Donaghers,” he said. That was Major Blackstone’s theory, and, since his conversation with Terran Chancelor that afternoon, regarding the Debney shooting, the possibility had stuck in his mind like a burr.

A muscle bunched in Vierra’s jaw. “Sí,” he said. “But there is no proof.”

Sam waited.

“The patrons who hired me, they want the right men. No mistakes,” Vierra went on. “And I do not have the option, as you do, of shooting them through the heart and bringing them in draped over their saddles. The patrons want them alive. The streets of a certain village, a day or two south of here, will run with their blood.”

A chill trickled down Sam’s spine. He had no love for these murdering bastards, and would just as soon draw on them as take his next breath, but the law was the law. Unless one or more of them forced his hand, they would stand trial, in an American court, their fate decided by a judge and jury. He didn’t give a damn what happened to them after that, but by God, he’d get them that far, whether Vierra got in his way or not. “I guess it all depends on who catches up to them first,” he said moderately.

Both men rose to their feet. Vierra surrendered the map he’d brought with him. “There is a train making its way north in ten days,” he said. “I have told a few people that there will be a fortune in oro federale aboard. We will see if the rumor reaches the right ears.”

Federal gold, Sam reflected. Cheese in a mousetrap.

“And you’ve got a pretty good idea where they’ll try to intercept the train,” he ventured, recalling Vierra’s map in perfect detail. “That railroad trestle downriver from here.”

Vierra smiled. “I am impressed,” he said. “The new schoolmaster has paid attention to the lesson.”

CHAPTER FOUR

“YOU WANT ME to do what?” Maddie gaped at Sam O’Ballivan’s copper bathtub, ensconced squarely in front of the schoolhouse stove. Terran had left the store early that morning, of his own volition, and she’d barely recovered from her brother’s change of heart when back he came, breathless from running all the way.

“Mr. O’Ballivan says to come quick, if you wouldn’t mind!” he’d cried.

Maddie had frowned, concerned. Elias James, the town banker and, for all practical intents and purposes, her employer, since he oversaw Mungo’s investments, expected the mercantile door to be unlocked by nine o’clock sharp, and in the six years she’d been running the general store, she’d never failed to do that. It was now eight forty-five. “Is there some emergency?” she’d asked, already untying the apron strings she’d just tied a moment before.

“He says it’s important,” Terran had insisted.

And here she was, standing in the schoolhouse, staring in consternation at Sam O’Ballivan and the bathtub she’d sold him herself.

“I want you,” Sam repeated patiently, “to show Violet Perkins how to take a bath.”

Maddie knew Violet, of course, and had sympathy for her. The poor child hung around the store sometimes, when school was out, hoping for a hard-boiled egg from the crock next to the counter, or a piece of penny candy. She mooned over the few ready-made dresses Maddie carried—most women sewed their children’s garments at home, as well as their own—and huddled by the stove for hours when it was cold or rainy outside. Maddie often indulged her with a plate of leftovers from her own larder at the rear of the store, pretending the food would go to waste if Violet didn’t eat it.

“Here?” she asked, noting that Sam had set out the bar of French-milled soap and the towel he’d purchased with the bathtub. “In the schoolhouse?”

“What better place?” Sam reasoned. He’d been sitting behind his desk, wearing spectacles and poring over a thick volume when she burst in. At Maddie’s appearance, he’d set aside the glasses and stood. “A school is a place to learn, isn’t it? And Violet needs to know how to take a bath.”

Flummoxed, Maddie spread her hands. “What about the other students?” she asked. “You can’t expect the child to undress in front of the boys—”

Sam smiled. “Of course not. The girls can stay—I suspect some of them could do with a demonstration. I’ll take the boys down to the river for their lesson.” He held up the cake of yellow soap from yesterday’s marketing. “I’ve noticed that Violet is generally the first to raise her hand. Let her think she’s volunteering.”

Maddie glanced at the schoolhouse clock, torn. It was nine o’clock, straight-up, and the mercantile was still closed. At that very moment Mr. James was probably looking out his office window, the bank being kitty-corner from the store, wondering why the customers couldn’t get in to buy things and whipping up a temper because of it.

“Why me?” she asked.

Sam smiled again. “You’re the only woman I know in Haven besides Bird of Paradise over at the Rattlesnake Saloon. I don’t guess it would be fitting to bring her in to teach bathing, though she’d probably agree if I asked her.”

Maddie sniffed. “It certainly wouldn’t be fitting,” she said, wondering how Sam O’Ballivan had come to make the woman’s acquaintance. Damned if she’d ask him, even if her life depended on it. She approached the tub and peered inside, already unfastening her cuff buttons to roll up her sleeves. “We will need water, Mr. O’Ballivan.”

“I’ve got some heating in the back room,” he said. “No sense in lugging it in here and pouring it into the tub if you weren’t going to agree.”

She sighed. “What about the store?”

“Well, I figured, as the owner, you could—”

Maddie flushed. “I am not the owner. I manage it for someone else, and I am accountable to Mr. James, at the bank, who serves as trustee.”

Sam frowned. “Oh,” he said.

“Yes,” Maddie confirmed. “Oh. By now, there are probably people standing three-deep on the sidewalk, complaining because they can’t get in to buy salt and tobacco and kitchen matches.”

Sam brightened. “I think I have a solution,” he said. “I’ll take the boys to the river another day. In the meantime, they can learn how a mercantile operates. We’ll make a morning of it.”

“You intend to take over my store?” Maddie asked, affronted. “Do you think it’s so easy that any idiot can do it?”

The schoolmaster smiled. “I don’t regard myself as an idiot, as a general rule. How hard can it be, filling flour bags and measuring cloth off a bolt?”

Maddie came to an instant simmer, but before she could tell the man what she thought of his blithe and patently arrogant assumption that keeping a thriving mercantile was something he could do one-handed, the pupils began to straggle in. She swallowed her outrage and stood as circumspectly as she could, letting her gaze bore into Sam O’Ballivan like a pointy stick.

When everyone was settled in their seats, Sam announced his plan. The boys would help him tend the mercantile, the girls would remain at the schoolhouse for a “hygiene” lesson.

The boys cheered and stomped their feet, and rushed for the door at an offhand signal from Sam. The girls sat, wide-eyed, waiting for enlightenment. Maddie would have bet not a one of them could have defined the word hygiene, but they had noticed the bathtub. They were all agog at the spectacle.

“Miss Chancelor will give the demonstration,” Sam went on, looking worriedly from face to face. “But we’ll need a volunteer to get into the tub.”

Sure enough, Violet’s hand shot up. “I’ll do it, Mr. SOB,” she cried.

“Mr. O’Ballivan,” Sam countered easily. “That’s good, Violet. I appreciate your willingness to take the initiative.”

Violet beamed. “Can I go to the privy first?”

The other girls giggled and Sam silenced them with a ponderous sweep of his eyes.

“Yes,” he said. “You do that.”