По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

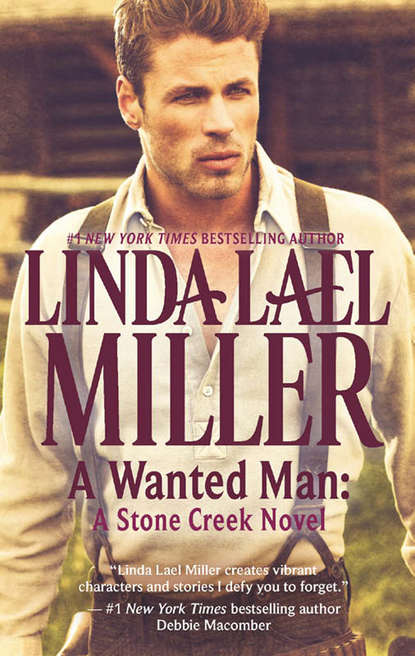

A Wanted Man: A Stone Creek Novel

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

There it was again, that little hitch between words, subtle but sharp as a tug on reins already drawn tight.

Gideon wanted to ask about it, but his audacity didn’t stretch quite that far. Rhodes’s manner was kindly enough, yet there was an invisible fence line behind it, enclosing places where it wouldn’t be wise to tread.

“You ever need any help,” Rhodes went on, when Gideon didn’t speak, “you’ll find me boarding at Mrs. Porter’s, over in Stone Creek.”

Gideon nodded. Stone Creek was a fair distance from Flagstaff, and he didn’t own a horse. Still, it was good knowing he could go there and expect some kind of welcome when he arrived.

Rhodes moved to rein his horse away, toward the road.

“Wait!” Gideon heard himself say.

The familiar stranger turned in the saddle, looked down at him.

“How many of you are there? Brothers, I mean?” Gideon blurted.

Rhodes smiled. “Five,” he answered. “Wyatt, Nick, Ethan, Levi and me.”

Gideon drew a step closer. “Are they Paytons?”

The answer was slow in coming. “No,” Rhodes said.

Gideon frowned. It was bad enough that he hadn’t known his own brothers’ Christian names. Now he wasn’t sure he knew who he was, either.

With a nod for a goodbye, Rhodes took to the road headed in the direction of Stone Creek.

Gideon watched him out of sight, half-sick with wondering. Then he bent, picked up the letter from the college in Pennsylvania, the only mail to come that day, and tucked it into his shirt pocket.

Without a fare-thee-well for Rose, he headed for Ruby’s place.

* * *

THE YELLOW DOG LAY in the doorway to Mr. Rhodes’s quarters as though guarding them, looking utterly bereft.

Lark, alone in the house because Mrs. Porter had gone to an all-day meeting at church and Mai Lee was off somewhere with her husband, Hon Sing, set aside the lesson plans she’d been drawing up, in preparation for the week to come, and regarded the animal with compassionate concern.

“He hasn’t left you—your master, I mean,” she told the dog.

Pardner, muzzle resting on his forepaws, gave a tiny whimper.

“Perhaps you’re hungry,” Lark said, getting up from her chair. Mr. Rhodes had given the creature table scraps the night before, with Mrs. Porter’s blessings, and he’d had leftover pancakes and a scrambled egg for breakfast.

While she certainly didn’t have the run of her landlady’s well-stocked larder, Lark had seen the heel of a ham in the pantry earlier, while seeking the tea canister.

But perhaps Mai Lee was saving the bit of ham for her hardworking husband. For all Lark knew, it might be the only thing Hon Sing had to eat.

No, she couldn’t give such a morsel to a dog.

In the end, she cut a slice of bread and buttered it generously, then tore it into smaller pieces. She was approaching Pardner with this sustenance when the kitchen door suddenly swung open and Mr. Rhodes strode in.

Pardner gave an explosive bark of jubilance and nearly trampled Lark in his rush to greet his master.

Mr. Rhodes bent, ruffled the dog’s ears, spoke gently to him and let him out the back door, following in his wake.

Lark, recognizing a prime opportunity to make herself scarce, stood frozen in the middle of Mrs. Porter’s kitchen floor instead, one hand filled with chunks of buttered bread.

Mrs. Porter returned before Mr. Rhodes reappeared, her cheeks pink from the cold and religious conviction. Beaming, she untied the wide black ribbons of her Sunday bonnet. “You missed an excellent sermon,” she told Lark. “All about the tortures of eternal damnation.”

“Sounds delightful,” Lark said mildly and with no trace of sarcasm, depositing Pardner’s refreshments on a chipped saucer and setting it on the floor. Having lived two years under Autry’s roof, she knew the highways and byways of hell, and had no desire to revisit the subject.

Mrs. Porter removed her woolen cloak and hung it on one of several pegs beside the door. “You really should consider the fate of your immortal soul,” she said.

The door opened again, and Pardner bounded in, his master behind him.

“Wouldn’t you say we should all consider the fate of our immortal souls, Mr. Rhodes?” Mrs. Porter inquired, looking for support.

“Rowdy,” Mr. Rhodes said. He watched Lark as he took off his hat and coat and hung them next to Mrs. Porter’s bonnet and cloak, probably noting the high color that burned in Lark’s cheeks.

His perusal made her uncomfortable, and yet she could not look away.

“Yes, indeed,” he told Mrs. Porter, in belated answer to her question. “I’ve run afoul of the devil myself, a time or two.”

If Lark had said such an outrageous thing, Mrs. Porter would have taken her to task for flippancy. Because Mr. Rhodes—Rowdy—had been the one to say it, she simply twittered.

It was galling, Lark thought, the way some women pandered to men—especially attractive ones, like the new boarder.

“You’re personally acquainted with the devil, Mr. Rhodes?” Lark asked archly, when Mrs. Porter went into the pantry for the makings of supper.

“He’s my pa,” Rowdy answered.

3

ROWDY RARELY LOOKED at Lark Morgan during the Sunday supper of hash, deftly made by Mrs. Porter since it was Mai Lee’s night off, but that didn’t mean he wasn’t aware of her.

He should have been thinking about his pa or about Gideon or about the meeting with Sam O’Ballivan and Major Blackstone coming up the next morning.

Instead the mysterious woman sitting directly across the table from him, intermittently pushing her food around on her plate with the tines of her fork and eating as though she was half-starved, filled his mind.

She hadn’t told him anything about herself. What Rowdy knew, he’d gleaned from Mrs. Porter’s eager chatter.

Lark was a schoolteacher, never married, popular with her students.

She’d been in Stone Creek for three months, during which time she’d never sent or received a letter or a telegram, as far as Mrs. Porter could determine. And Mrs. Porter, Rowdy reckoned, could determine plenty.

Lark Morgan’s clothes gave the lie to a part of her story—they were costly, beyond the means of any schoolmarm Rowdy had ever heard of. He wasn’t convinced, either, that she’d never been married; there was a worldliness about her, as though she’d seen the seamy side of life, but an innocence, too. She’d been a witness to sin, he would have bet, but somehow she’d managed to hold her expensive skirts aside to avoid stepping in it.

Mentally Rowdy cataloged his other observations.

She’d dyed her hair—there was a slight dusting of gold at the roots.