По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

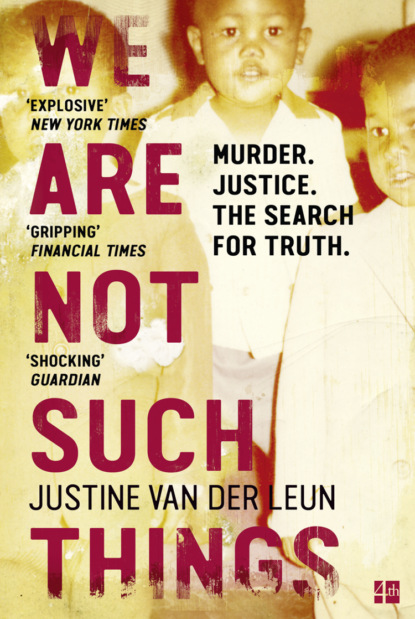

We Are Not Such Things: A Murder in a South African Township and the Search for Truth and Reconciliation

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

British Parliament therefore sent over orders for their people to execute homicidal commando raids of “kaffir” villages (“kaffir” was initially used to refer to non-Christians, but eventually became a derogatory term for a black person), during which women and children were slaughtered and cattle stolen. Desperate Xhosa guerrillas nearly won a battle to reclaim land, but were ultimately dispossessed of even more territory and lost 23,000 cattle. After leading conquests in 1811 and 1812, the Cape’s governor, Sir John Cradock, cheerily reported back to London on the success of these attacks: “I am happy to add that in the course of this service, there has not been shed more Kaffir blood than would seem necessary to impress on the minds of these savages a proper degree of terror and respect.”

In 1820, four thousand British citizens—poor artisans, mostly, unaware of the battles being fought in South Africa and hoping for their own property allotment—were shipped over and handed one hundred acres each of the rough and wild eastern Cape. These inexperienced farmers found themselves out of luck: they were stranded in the middle of a simmering series of frontier wars, about which they had not been informed when they applied to go to Africa. To add insult to injury, the grasslands were difficult to cultivate without the generational wisdom the Xhosas possessed. Within a few years, many of the sour-grass plots were abandoned as the British took refuge in the settlements of Grahamstown, Port Elizabeth, and East London.

For their part, the Xhosas were fractured, grief-stricken, plunged into poverty: over the years, they had lost their land, many of their animals, and their communities to settlers. Unable to come to terms with their sudden reversal of fortune, they became convinced that this onslaught of misery had been brought on by furious ancestors. A young female prophet reported that if the tribe slaughtered their remaining livestock and stopped planting crops, they would be forgiven and rise again, and so the desperate people abided by her word. By 1857, the population was starving. The Xhosa people would mount various offenses to secure the return of their land, but ultimately the majority of them realized that their only survival option was to work at a pittance for the white farmers who now tilled their former land.

Amy Elizabeth Biehl came into the world 315 years after the Dutch landed on the Cape and 110 years after the Xhosa people faced what then seemed to be their darkest hour. She was born on April 26, 1967, in Chicago, Illinois, to loving, upper-middle-class parents. It was a cool and hazy spring Wednesday, and a light rain drizzled down on the lakeside city. She died on August 25, 1993, in Gugulethu, Cape Town, at the hands of a violent mob of students, gangsters, and unemployed young people. It was a clear winter Wednesday, 78 degrees and unseasonably sunny.

Journalists often misidentified Amy as a “volunteer,” an “aid worker,” or an “exchange student.” Some referred to her as an “angel” or a “golden girl.” When she died, the headlines were melodramatic and simplistic:

A WOMAN WHO GAVE HER LIFE TO AFRICA

PRAISES SUNG BY ALL

DEATH OF AN IDEALIST

POOR AMY

In fact, Amy was a serious academic and an activist, but she didn’t present as the widely held caricature of the intellectual, at least not in photos. Amy was female, first of all, and she was conventionally pretty. She had long dirty-blond hair, straight teeth, and a spray of freckles across her delicate nose. She had fashionable clothes bought by her father and a sense of style inherited from her mother, who in her later years became a couture saleswoman at Neiman Marcus in well-heeled Newport Beach. She was slender from years of competitive sports. She was confident in her opinions but modest and allergic to causing offense. She had good posture and a decent handshake. She was not above telling a bad joke.

Amy had not wandered blindly into Gugulethu that August day, some ignorant missionary who thought her smile could cut through the fury of a disenchanted and dispossessed generation of blacks. She knew there was a storm brewing in South Africa. She’d majored in African Studies at Stanford, and at graduation she had plastered the words FREE MANDELA in masking tape across her cap, which her grandmother, a Midwestern Republican, kept trying to pick off. After Stanford, as an employee of the nonprofit National Democratic Institute, Amy had traveled to South Africa, Zambia, the Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Burundi, and what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 1989, she spent time in Namibia, which was holding free elections as it transitioned to independence from South African rule. She traveled there again in 1991 to study the early workings of a new parliamentary democracy. She even went on a jog through Lusaka, Zambia’s capital, with Jimmy Carter.

By the time Amy landed in South Africa in September 1992, she was well versed in the long-standing issues of liberty, race, and rights that had shaped postcolonial African discourse. She was especially interested in the country as apartheid began to crumble and Nelson Mandela’s rise to the presidency became increasingly inevitable. She wanted to be in the middle of the action. So when Amy landed her Fulbright, she packed her bags and Linda drove her to Los Angeles International. In the waiting area, Amy fell into an engrossing conversation with another passenger, who was also up-to-date on South African politics. Distracted, she hugged Linda goodbye. Though they spoke on the phone during Amy’s ten months in South Africa, the last words Amy delivered to Linda in person were a parting command as she boarded the plane: “Don’t cry, Mom.”

In Cape Town, Amy immersed herself in her research topic: the rights and roles of women, primarily black and colored women, in an emerging democracy. She traveled into the depths of the townships and witnessed firsthand the squalor in which black people were forced to live under apartheid law. Diplomatically inclined and tactful, Amy rarely expressed, verbally, the effect this inequality and racism had on her. Perhaps she knew it was not her place to complain, that the emotions of a white American on the subject of state-sanctioned racism were hardly relevant. But sometimes she let it rip. Once Amy and her boyfriend, Scott Meinert, who was visiting from the States for a couple of weeks, wandered into an all-white bar wearing T-shirts emblazoned with Mandela’s face. The patrons unhappily received two white kids with a black opposition leader plastered across their chests, and some spit a few under-the-breath comments at the pair: “Like the darkies, do you?” Amy ignored them, drank her beer, and strode back to the parking lot, where she got in her car and started hitting the dashboard with all her might and letting fly a stream of profanities. She was furious at herself for taking the high road.

While in Namibia, Amy met some rising ANC dignitaries, including Brigitte Mabandla, who would become minister of justice and constitutional development in post-apartheid South Africa. The late 1980s and 1990s were prime periods in the history of what is referred to as the Struggle, or the long fight for freedom. Back then, high-ranking ANC members were often also professors, and Mabandla headed up the Community Law Center at the University of the Western Cape. Inspired, Amy chose to conduct her South African Fulbright-funded research at the University of the Western Cape instead of the more prestigious and whiter University of Cape Town. At UWC, a university historically designated for students of color, she drafted memos for Dullah Omar, Mandela’s lawyer who would become the president’s minister of justice, and for Rhoda Kadalie, an intellectual and activist who would become Mandela’s commissioner of human rights. Rhoda was then a single mother in her late thirties, and she and Amy grew especially close over the months, discussing politics, feminism, policy—and boyfriends, sex, and gossip. On the day of her death, Amy was clearing out her workspace at UWC, organizing her papers, and packing up any spare notes as she prepared to head back to America. She used a university phone to call Rhoda, who was working from home that day, and they spoke for nearly two hours.

“Rhoda, I’m so sentimental for this place,” Amy said as their conversation finally neared an end. She had filled her suitcases with patterned cloths for friends at home and CDs of local musicians. She had sold her car, which she planned to deliver to the buyer the next day. Rhoda and Amy agreed to meet up for lunch one last time before Amy flew out. As they hung up, Rhoda told Amy to stay away from the townships. The radio was abuzz with news of protests, rallies, and stonings. Marching kids were smashing up government property and attacking government-employed health workers. Amy knew all this. She was lucky, she remarked, that she’d made it all this time without anything ever happening to her.

“There’s a lot of unrest,” Rhoda ordered in her clipped voice. “You will not go in today. Do you understand?”

Amy said she understood. She was well aware of the thousands of lives lost, most of them black, in the fireballing political strife of the last several years—the early 1990s, after Mandela was released from prison and negotiations for the first inclusive democratic elections began, saw the country on the brink of a civil war. Anyway, she didn’t have time to go to the townships. She had been renting a room from a friend and colleague named Melanie Jacobs, and lived with Melanie and Melanie’s teenage daughter in a small flat in the relatively diverse suburb of Mowbray, about eight miles from the townships. Amy needed to go back to Mowbray to see her friends; she had less than forty-eight hours before she hurtled toward California, where she planned to go with her family to consume margaritas at her favorite Mexican restaurant, Mi Casa. You can’t get a proper margarita in South Africa.

Amy didn’t know that Scott planned to propose to her when she arrived. On the evening of August 25, on the west coast of America, Scott had a dinner date planned with Peter Biehl, to ask for his blessing. Amy was a liberal feminist, but Scott suspected she wanted a traditional engagement: Dad’s permission, one knee, Champagne. If life had taken a different turn, would Amy have said yes?

“We don’t know that,” Linda told me.

“Oh yeah,” her college friend Miruni Soosaipillai countered. “I have a memory of her saying that she felt like she was ready. They had been together for something like six or seven years.”

But no matter what, Amy would only be home for a few days, just enough time to see some friends, her mom and dad and sisters and brother, and pack her bags again. She was heading for Rutgers University in New Jersey. She had recently been awarded a fellowship to pursue a PhD in international women’s studies. After that, she would become an academic—or perhaps a policy adviser in government. In her dreams, she would launch her own NGO, a serious, research-based organization that would help protect the rights of women and children in African countries that were transitioning from colonial oppression to free democracy.

A half mile from Amy’s office, two UWC students, Sindiswa Bevu and Maletsatsi Maceba, stood on the main road, trying to hitch a ride. A friend had promised to drive them home, but had forgotten about them, and now they were a pair of young black women, arms out, looking to be dropped near an area deemed unsafe by most locals. For the past week, the radio had been reporting that the townships were burning and high school kids were trying to kill cops and overturn government vehicles.

There was also the quotidian township violence, stoked by the political situation. The day before Amy’s death, somebody was stoned and two people were attacked in Gugulethu. Two hours before Amy entered the township, a homeless man was robbed by an unknown assailant. A half hour before Amy drove in, several more people were stoned. At various points throughout the day, three men were separately attacked. That afternoon, two residents were robbed, two homes were burglarized, and somebody was arrested for “possession of ammunition.” There were two separate reports of “public violence” and one report of “grievous bodily harm.” Of all the other crimes that were committed in Gugulethu on August 25, only one man was arrested: according to police records, a “non-white” squatter camp resident had stabbed another “non-white” squatter camp resident to death, for which he was sentenced to just five years in prison.

For the most part, the victims and perpetrators were black and colored residents of various townships and their misfortunes warranted minimal attention. One exception to the rule occurred at around eleven that morning, five hours before Amy was attacked. A white man employed by the city had been helping to fix a buzzing light out by Heideveld train station. Heideveld station straddles the colored area of Heideveld and Gugulethu, the tracks connected by an overhead footbridge. The white man, working on the Gugulethu side, was pulled from his truck by a mob of young black locals, stomped, stabbed, and left for dead. Despite the race of the victim, that crime, too, escaped the attention of law enforcement or media. There was neither an investigation nor a single arrest. Later, I was to find out a heretofore unreported and improbable link between that obscure, forgotten crime, with its two decades of pain and suffering that followed, and what happened to Amy that day.

Sindiswa and Maletsatsi waited forty-five minutes, but nobody would pick them up, so the women trudged back to campus. There they found Amy clearing out her office. They asked her for a lift. Despite her promise to Rhoda to stay away from the townships, Amy agreed to drive Sindiswa and Maletsatsi home.

“I always say she went because she forgot she was white,” Rhoda told me. As a white person who has spent years doing research and interviews in Gugulethu, I find this alleged slip of memory to be nearly impossible. I am never quite so searingly aware of the color of my skin as when I am in the township.

In the parking lot, Amy passed by Evaron Orange, a nineteen-year-old cousin of Amy’s roommate, Melanie. He was a baby-faced colored kid with a caterpillar mustache and oiled black hair. He also needed a lift, and so Amy agreed to take Evaron to Athlone, the nearby colored neighborhood where he lived.

The four loaded into Amy’s dinged-up beige Mazda. Evaron sat in the passenger seat and the two women slipped into the back. The Mazda was all muddy tones: tan fabric seats, dull brown carpeting, a dark brown dashboard. Its only pop of color was a bright yellow Cape Town license plate, its only adornment a squat rectangular sticker plastered on the back right bumper, just below the taillight, printed with unadorned black capital letters: OUR LAND NEEDS PEACE.

Amy drove her friends southwest on Modderdam Road, passing the bleak industrial yards of Parow and the Bishop Lavis ganglands. She drove by the flat, crumbling pastel houses that lined the broad thoroughfare, and at the four-way intersection that separates the black townships of Gugulethu, KTC, and Crossroads from the colored townships of Bonteheuwel and Valhalla Park, she turned left onto NY1. NY stands for Native Yard, the lingering apartheid designation for streets in black townships, all of which were simply initialed and numbered: Native Yard 32, Native Yard 58, Native Yard 79, Native Yard 111.

Amy had been to the townships dozens of times, to drink and dance at the clubs and shebeens, the taverns that provided relief from the daily grind of apartheid and poverty, and to visit friends and conduct research. Driving along NY1, she passed the brown-brick Shoprite Center. She continued over a small overpass that stretches above the N2 highway and connects the northern corners of Gugulethu to the rest of the world. On that day, as rush hour neared, traffic was congested on NY1, which offers only a single slender northbound lane and a single slender southbound lane, hemmed in between sidewalks. After the turnoff, Amy followed a small truck down NY1.

She drove past the shoulder-high grass on the outskirts of Gugulethu. She slowed down as she went by the police barracks contained behind razor wire, past the long municipal buildings that comprised the elementary school. Now there was traffic. She edged nearer to the Caltex service station laid out on the corner of NY1 and NY123. The station was positioned just off the road, its six pumps sheltered by a red cement overhang and set next to a low gray-brick building where the cashiers worked behind bulletproof glass.

A quarter mile past the Caltex sat the Gugulethu police station. Amy planned to drop the women near the police station, where she could safely turn around and go off to Athlone with Evaron. But just before Amy reached the Caltex, the truck in front of her stopped short. She pressed the brake.

“Ride, ride,” Evaron said.

“I can’t.” Amy gestured before her at the truck, which was shaking. In South Africa, as in the U.K., people drive on the left, so to Amy’s left was a sidewalk, and to her right was a line of bumper-to-bumper cars traveling in the opposite direction. Ahead, they could make out a group of young people, some of whom seemed to be pressing against the truck.

A man from that group turned and zeroed in on Amy, her pale face shining. The man yelled out and the other young men swiveled around. There is a word in Xhosa, iqungu. It’s similar to the English term bloodlust. It means “the joy in killing.”

The men and boys were speaking Xhosa, yelling to each other. Amy and her friends sat, paralyzed and uncomprehending. One man held in his hand a cracked brick, tan in color, plucked from construction refuse on the side of the road. No, many of them had bricks, almost all of them had bricks or stones clutched in their hands. Now Amy and her friends could see that up the road, ahead of the truck, the crowd was moving, chanting. That first man raised his brick and hurled it toward Amy, fast and straight. The force shattered the windshield, which exploded with a loud cartoon pop. Droplets of glass flew across the car’s interior, coating the seats, the floor, wedging in the clutch, getting stuck in clothes and hair and shoes. Later that night, when Evaron took a bath, he found shards of glass nestled in the seams of his underwear.

Unthinking, disoriented, Amy drove onward. Another brick came, this one on a perfect trajectory, with no windshield to break its flight. It connected with Amy’s face, hitting her square above her right eyebrow. Her head snapped back and then forward. The brick cracked her skull easily, like an eggshell. It left a three-centimeter-long piece of bone, shaped like an arrowhead, hanging loose. The arrowhead bone briefly pressed against her soft pink brain, now exposed.

Blood poured from Amy’s forehead, drenching her hair. She drove a few more yards down NY1, her right arm dangling from the window, before she stopped. A skinny young boy popped up near her. He looked at the four of them sitting there, slipped the watch off Amy’s limp wrist, and melted back into the crowd.

From inside the car, it seemed that the sun had disappeared and the sky had gone black. The stones hailed down. In the backseat, Sindiswa and Maletsatsi began to scream. Evaron pulled Amy onto his lap.

“Oh dear Lord, help me,” he whispered.

There were people all around, shouting. Now you could make out the words, if you listened.

“One settler, one bullet,” the people chanted.

“Africa for Africans.”

“Kill the farmer, kill the boer.”

“Boer” is the Dutch word for farmer. In South Africa, farmers, primarily Afrikaners, grabbed swaths of land that previously belonged to indigenous people and then employed blacks as sharecroppers or low-paid laborers and kept the profits.

A woman stood on the sidewalk across the way. She yelled at Amy and her friends over the slogans.

“Get out!” she implored. “Run, run, run!”

“Run,” urged other disembodied voices, locals standing at a distance who had seen this grisly show before, though never starring a white woman. If a mob surrounds you, you only have one sorry choice: Run, run, run.

More young people were pouring in from NY109, where a path from the train station met NY1. Others were already ahead, blocking traffic. There seemed to be more than a hundred of them, or perhaps it was just eighty. They were engaged in a toyi-toyi, a beautiful, terrifying march-dance originally from Zimbabwe, in which a coordinated group of people lift their knees up high and wave their arms above their heads as they chant and move in protest. As Amy lay on Evaron’s lap, the chants grew louder and clearer and some kids began to lift the car up, hoping to roll it.

“One settler, one bullet.”