По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

A Great Task of Happiness: The Life of Kathleen Scott

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

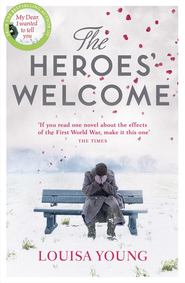

Also by Louisa Young (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_97e2d819-d312-58fc-8a39-c0a251234bf2)

In the course of my parents’ fortieth wedding anniversary party in 1988, I was sitting on the old green velvet sofa at their house in Bayswater with my ancient cousin Verily, who was hooting with laughter. She told me that a good sixty years ago she’d been sitting on that same sofa in that same room with my grandmother Kathleen, her aunt, and that I was saying exactly the same thing that Kathleen had been saying. I think it was something about how lovely it is to sleep out of doors. Kathleen always slept out of doors, given half the chance. In Bayswater she slept on the balcony.

Kathleen was my father’s mother. She was born in 1878 and died in 1947 so I never knew her, but statues she had made were all over the house and garden, and sometimes my father would point one out in a public place: Adam Lindsay Gordon in Westminster Abbey; Lloyd George in the Imperial War Museum, and The Man Who Wasn’t My Grandfather on Waterloo Place. I knew he wasn’t my grandfather because my grandfather had only one arm and wasn’t all bundled up. Gradually I realised who he was: Con, Captain Robert Falcon Scott, her first husband; and that he was heroic and tragic and had died of cold and hunger in a tent in a blizzard in the Antarctic, having got to the South Pole too late. I knew this was unspeakably sad but I was worried too because if he (and Oates and Evans and Bowers and Wilson) had come back, Kathleen would never have married my grandfather, and my father and I and my five siblings would never have been born. I wondered if Uncle Pete, who was nine months old when he last saw his father, minded about us. I realised quite soon that he probably didn’t, as he had named a family of swans after us.

Kathleen had written a short autobiography, largely for her own pleasure, in 1932; it was published along with a tiny selection from her thirty-six years’ worth of diaries after her death. I read it when I was sixteen, and was delighted to find that a grandmother could have lived like a vagabond on a Greek island, could have had friends who got pregnant out of wedlock, could have been annoyed by the hounding of the press, could have worried about what to wear, could have fallen in love and ridden with cowboys, could have run away to Paris to be an artist, and to Macedonia to tend to refugees, could have been financially independent and brought up a son alone. Equally I was shocked to find that a grandmother—my grandmother—could have not supported female suffrage, could have visited South Africa and not exploded at the injustices there, could have moved happily in circles where people referred to ‘little Jews’. I had to accept that I could not in justice expect one woman within her generation to be in every way ahead of that generation in matters of humanity and justice. Things unacceptable to me now were generally accepted then; some of them (not all) Kathleen accepted.

But then the humanity in her friendships, with passing strangers or with famous people—George Bernard Shaw, Isadora Duncan, Asquith, Sir James Barrie, Lawrence of Arabia, Max Beerbohm, Austen Chamberlain, Rodin, Colonel House—delighted me. The details of how a woman was, and how women could be, in those days, were fascinating. She was funny and adventurous and innocent and proud. She travelled all over the world. I was pleased to be descended from her.

I was thirty before I realised I could read all her diaries, written almost every day for thirty-six years. She started them for Con when he went south; they were to be a record for him of their son and of her day-to-day activities. After she learnt that Con was not coming back she kept them up. No one knew she did. Her handwriting races along (illegible unless you really practice reading it) recording adventures, anecdotes and observations, interspersed with photographs and little sketches, from 1910 to 1946. They cover politics and exploration, art and sex, literature and travel, Mexican trains and plastic surgery, love and death, folly and creativity, childbirth and flying, iguanas and vicars and eating chicken sandwiches out of her coronet at the coronation of George VI. They notably lack self-absorption, self-pity and self-indulgence. I realised that the story sitting in her papers—she kept many letters too—at the University Library in Cambridge was begging to be searched out.

My father wanted me to do it and, if I mentioned her, people would say, ‘Oh, now I know something about her, wasn’t she the one who … /Didn’t she … /I remember in so-and-so’s biography she... /My mother told me about her… Oh yes, she was extraordinary, wasn’t she?’

Then I heard Beryl Bainbridge say on the radio one morning that really someone should write Kathleen Scott’s biography, and I was seized with fear that someone else might. So I did. It is not a history of the first half of the twentieth century, a discourse on feminism and the Empire, or another contribution to the well-documented and much-discussed arguments over the comparative merits of dogs/ponies/skis/motor sledges in pre-First World War Antarctica, or what really happened to the oil supply at the Southern Barrier depot. It is the story of a woman’s life. There is no special reason why it should be extraordinary but it is.

Louisa Young The Lacket, 1994

Introduction to the new edition

This was my first book and time has passed. It is now a hundred years since Con was at the South Pole; sixteen years since this book was first published. Kathleen’s son Wayland, my father, has been dead nearly two years, and Kathleen herself has reappeared in fiction, casting the face of the wounded hero of my novel My Dear I Wanted to Tell You. This new edition has been corrected and updated, and I have added various interesting things that have come to light since the first edition came out.

Louisa Young London, 2011

ONE Motherless Daughter, Victorian Child (#ulink_0e300957-26a0-5b0e-9cc8-706573287df3)

1878–1898

KATHLEEN BRUCE wanted written on her gravestone: ‘No happier woman ever lived’. The first thing to happen to her, however, was that her brother—her favourite brother—slapped her face, complaining that her eyes were too red. Then her mother went blind and died. Then her father died, then her great uncle who had been looking after her. Then she was packed off to school, and then she ran away to Paris to study with Rodin, then to Macedonia to sit in freezing mud and give blankets to the dying. She nearly died there in an epidemic of typhoid fever, and again later during surgery. She helped to deliver Isadora Duncan’s illegitimate child. At twenty-nine she found love with a man named Robert Falcon Scott, married him and had a son. A year later her husband died, frozen and starving on his journey back from the South Pole. By the time she found out, he had been dead a year. After that things looked up a bit.

Kathleen was descended from the brother of the fourteenth-century king of Scotland, Robert the Bruce, of cave and spider fame. On her grandmother’s side she was descended from Nicolae Soutzo, who was in turn Grand Drogman of the Sublime Porte, Grand Logothete, Grand Postlenik of Wallachia and Grand Cepoukehaya, and decapitated in 1769. This side of the family was Phanariot: Greek from Constantinople. The glorious titles denoted positions in the Turkish imperial rule of central Europe. An early ancestor was Michael Rangabe, Michael I, who was Emperor of Constantinople for a very short time in the year 800. His son married an illegitimate daughter of the rather more successful Emperor Charlemagne, who brought as part of her dowry a little fishing village now known as Venice.

One thousand and thirty-two years later their descendant Rhalou Rizo-Rangabe, aged sixteen, was frightened by a mastiff in a street in Athens: so frightened, she said, that she rushed into a nearby house and jumped on the table. The dog’s master, a twenty-one-year-old soldier from Edinburgh named James Henry Skene, over from Malta to shoot duck, followed her in, lifted her off the table and fell in love. They were Kathleen’s grandparents. Rhalou was the daughter of Jacovaki Rizo Rangabe, the last Grand Postlenik of Wallachia, and Princess Zoe Lapidi; James was the son of Sir Walter Scott’s best friend, James Skene of Rubislaw, a brilliant watercolourist whom Scott described (in the preface to Ivanhoe) as ‘the best draughtsman in Scotland’, and who is the only non-Greek to have a room devoted to his work in the National Gallery in Athens. James junior’s mother was Jane Forbes, whose great uncle, Lord Pitsligo of Monymusk, had dashingly served the Young Pretender, disguised as a beggar, at the age of seventy.

James and Rhalou were married in 1833. Later James’s sister Carrie married Rhalou’s brother Alexander Rangabe. James sold his commission in the King’s 73rd (later the 2nd Black Watch) to become a writer and diplomat, and they moved in with his parents, who, following their children’s example, had moved to Athens. James and Rhalou had seven children, including a daughter named Janie after James’s mother: she was to be Kathleen’s mother. The children’s aunt, Fifi Skene, would take them on walks to the Acropolis and tell them how the caryatids wept each night for their sister, kidnapped by wicked Lord Elgin (who was another cousin) and imprisoned in the British Museum; and their Greek nurses told them tales of Turkish cruelty. The family travelled a great deal: James Skene lived ‘as a sheik’ in Syria, and Fifi took the children to Paris, introduced them to a pasha’s wife in Bulgaria and, when the opportunity arose, showed them slaves being sold in the market and the head of a decapitated bandit.

When Janie was seven the Skene grandparents returned to Britain, and Janie and her sister Zoe, aged eight, went too. They lived a while in Oxford, where the sisters took lessons with dons and attended lectures. At seventeen Zoe married Dr William Thompson, a cleric who seemed to be promoted every time Zoe had a child: when he became Archbishop of York, Bishop Wilberforce commented that Mrs. Thompson had better be careful, because ‘there are only Canterbury and Heaven before him’. (Their son Basil became prime minister of Tonga.) Janie was twenty-seven when she found a priest of her own, the Rev. Lloyd Bruce, whom Zoe described as ‘dull, shabbily dressed and too old’ (he was thirty-four). Janie felt otherwise: ‘Oh, dear Zoe,’ she wrote, ‘I wish you could see him a little more with my eyes!’ In 1863 they were married at St Michael’s, Oxford.

Janie was energetic and charming and something of a beauty: she posed for Rossetti. However, her health was intermittently bad. Having six children (including two sets of twins) in three-and-a-half years did not improve it, though she said it was the raising not the bearing that wore her out. In 1868 she had a complete collapse and had to be fed at half-hourly intervals:

Janie largely recovered from this illness (hysteria, said a London specialist, and who could blame her on that diet?) and on the advice of her doctor had more babies. Between times she took to illustrating photo albums with beautiful pictures of flowers, to raise extra money for the family (the pre-Raphaelite William Riviere had taught her to draw in Oxford). Zoe would sell them for three guineas each. The Bruces were not as well off as Zoe’s constantly elevated family, and Zoe continually (and in the face of Janie’s well-bred protests and deeply felt gratitude) plied them with petticoats and soldier outfits and whatever was needed. ‘You really are a witch to find out our wants as you do,’ Janie wrote.

In 1878 the Bruces were living in the Jacobean rectory at Carlton-in-Lindrick, near Worksop. It was a grand place, with stables and a lake, a millpond, pillars in the drawing room and Italian mosaic floors upstairs, and a garden large enough to hold the village fête in. Archbishop Thompson was to thank for putting this suitable living the way of his impoverished but fecund brother-in-law. Here Janie gave birth to her eleventh child, which made it another five in seven years. This last, born on 27 March 1878, was Kathleen.

Kathleen weighed eleven pounds when she was born, and her hands were nearly as big at birth as those of her two-year-old sister Jane. Jane, known as Podge, and the littlest brother, Wilfrid, were taken in to see the new baby: Wilfrid stared at her, slapped her face and ran away. Podge remembered Kathleen as a baby ‘scrambling over poor unfortunate mother’. Not surprisingly, Janie was ill again. She wrote to her sister Zoe, telling her everything the doctor had said: ‘I am using my spectacles … they do not help me as yet as much as I had hoped … failure of sight . .. disease of the kidneys … paralysis of the optic nerve … my heart etc. is weak… I might have burst a little vessel in the brain.’ She finished up admitting that ‘I have given you a horrible history of my proceedings.’ But the proceedings were horrible. She went to the seaside for a couple of days to rest, and wrote again to her sister, in pencil: ‘I have been very badly since Thursday, two days in bed and two days creeping around wrapped in a shawl …’ She had slept in a damp bed, but didn’t want to make a fuss and get the servants into trouble. On 1 October 1880 she died of pneumonia, aggravated by what was known then as Bright’s Disease—inflammation of the kidneys. She was forty-two, and her youngest daughter was one.

Kathleen, writing in 1932, recalls her mother thus: ‘This long suffering lady went blind when I was born, and for the brief time that she lived afterwards she lay gently feeling her last lusty baby’s face, tracing the small features. Even a dozen had not taken completely from her the sense of the miraculous. How would it have been had she been able to hear, twenty, thirty, forty years later, this same me stretching out my arms to love, or the sun, with a “Thank God my mother had eleven children; just suppose she’d stopped short at ten!”’

The day Janie died Kathleen was propped in the windowsill of the day nursery as the servants passed through from the back stairs to the front stairs, and then back again, weeping and covering their faces with their aprons. Then Aunt Zoe Thompson took Kathleen, Podge and Wilfrid into the spare bedroom and told them, crying, that their mother was dead. Podge claimed it meant ‘nothing, absolutely nothing’. She was speaking for herself. Some years later she and Kathleen saw the corpse of a man who had fallen from scaffolding and been killed: Kathleen was haunted by the sight of his boots sticking out from under the blanket on the stretcher, they filled her ‘with every form of creepiness’, but Podge ‘had no such feelings. Death and dead bodies never affected me.’ The same cannot be assumed of Kathleen.

The Bruces were very much a Victorian family: huge, resilient, religious, stiff-upper-lipped, and with a streak of eccentricity. They were brought up on Robinson’s Patent Barley and Groats, with nursery maids, schoolrooms and white pinafores. Lloyd Bruce was by this time a canon of York and used to pay his little daughters a halfpenny a time to collect wheelbarrows of weeds, and tell them not to spend their earnings all at once. Though he had adored Janie and was grief stricken at her death, nine months to the day later he married a well-to-do widow from Sheffield named Mrs. Parker, who he hoped and believed would help with the children. She had a bonnet with both roses and feathers on it, and the elder children were not at all sure about her, even though she had been a friend of their mother. Douglas, the eldest boy, suggested that they call her mother in gratitude for her coming to look after them, but Rosslyn, the seventh child, said he would only ever call her Mrs. Parker. The only benefit he saw was the fact that Mrs. Parker’s sister was married to Sir Luke Mappin, who had built the bear and goat terraces at London Zoo. Even that didn’t help much. Rosslyn had a performing flea, and when Lady Mappin came to stay there was uproar because it was discovered on her ladyship’s pillow. ‘Sorry,’ said Rosslyn, ‘that’s not mine. Mine is a cock flea. That’s one of her own.’

Podge recalls nothing between her mother’s funeral and being instructed to put on a clean pinafore to go and meet her ‘new Mamma’. The Canon married for the children’s sake, and Mrs. Parker herself was not entirely happy with the situation. Although eventually all the children came to call her Mamma, she felt that she was ‘only Mrs. Bruce’. She did try to enter into the spirit, but even Elma, the eldest sister and the ‘sensible one’, said that whereas her mother had been ‘all gentleness and humility, this one was all pomposity and boss’. Mamma took a great fancy to the toddler Kathleen, and used to read picture books with her after lunch. A favourite was called Wee Babies; Kathleen specially liked the part about the twins Horace and Maurice, who were so alike their nurse couldn’t tell them apart—this is the first appearance of a lifelong inclination towards males, babies, and in particular male babies. But Mamma did not work out. On one occasion she slapped her husband’s face during a dispute about the fish for dinner; after that she took to spending long spells abroad. No one else took much notice of Kathleen.

Podge’s first memory of Kathleen was of her in ‘a white woolly pelisse and cape, the latter ornamental round the edge with little woolly blobs which you invariably sucked and pulled off. I remember Rachel the nursemaid’s grief to find another blobble gone, as usual.’ Rachel was popular, and Mamma’s sacking her (because she was rather vulgar and could not sew) did not endear her to her new family. The new nurse was called Emma; she had been Janie’s maid and Kathleen used to get into her bed every morning and learn German words and prayers. Podge would amuse herself at night by making ogre faces at her baby sister over the edge of her cot to make her cry, until the nursemaids in the room below banged on the ceiling with a broom handle to make them stop. Podge never knew where the banging was coming from, but she knew what it meant.

The Canon was not well, Mamma was largely absent, and Elma was taking over as the organizer of the brood—their great uncle Sir Hervey Bruce even referred to her by mistake as ‘your Aunt Elma’ rather than ‘your sister’. Several of the children, including Podge, were dispatched to Edinburgh to stay with their great uncle William Skene, Janie’s uncle, the brother of James and Fifi Skene, to lighten the load. He was perfectly accustomed to this: for the past fifty years his house in Inverleith Row had rarely been without nephews and nieces and great nephews and great nieces staying. In between being Historiographer Royal for Scotland, a writer and scholar of Celtic and Gaelic history and a family lawyer, he liked to take them swimming (even in his old age) and tell them tales of Highland history.

Kathleen said later that Mamma ‘appeared to take little or no interest, either during her life or at her death, in the healthy, good-looking, good-humoured army of her step-children’, but this may not be quite fair. Mamma offered to take Kathleen as her own child when the others were going off to Edinburgh, and the fact that this offer was rejected may have had some bearing on her deathbed reluctance to leave her worldly goods to the family with whom things had not worked out very well. Kathleen stayed on a year with her father and big sister Irene, who ‘took you for her doll’, as Podge put it, dressing her up and calling her Baby. Podge, in Edinburgh, missed her little sister, regretted the ogre faces and cried herself to sleep at night resolving to protect Kathleen in future. When, at the age of seven, Kathleen joined her siblings at Great Uncle William’s, the protection was needed. On one occasion, Podge reported later, ‘we were all jumping from trucks filled with sand (to be used for the erection of the Forth Bridge) on to the sandbanks. You were a timid child and flunked jumping from the same height as they did who were several years older. One of them got behind you and pushed you down—your mouth, eyes and nose were covered with sand. I boil now when I think of it.’

In many ways the Bruce children’s life in Edinburgh is reminiscent of E. Nesbit’s Five Children and It, only there were more of them. William Skene was an amiable though strictly Episcopalian academic with no children of his own. Elma and Zoe, the first twins; Irene, Douglas, Lloyd and Gwen, the second twins; Rosslyn, Wilfrid, Hilda (known as Presh), Podge and Kathleen ‘generally struck out an original line of our own, and none of us were ever at a loss to know what to do with ourselves,’ Podge wrote. ‘We were very independent and hated to be interfered with.’ One governess suffered for weeks after being so ill-mannered as to wonder whether Kathleen had brushed her hair properly. (Brushing hair was a subject fraught with pitfalls. One of the worst accusations you could make to an Edinburgh child of the time was that she ‘brushed her hair underneath’—presumably to do with vanity, or laziness, or both. Kathleen’s hair was so long and thick that she was called ‘lanky locks, chatterbox’ even though she was rather a quiet child.)

Ostensibly well brought up, in navy blue jerseys with white lace collars, a neat ribbon at the neck and always a hat, they were in fact a bunch of little monkeys—Elma, Zoe and Irene excluded. The eldest brother Douglas is remembered with his feet up on the nursery mantelpiece, eating sweets; Presh christened their black straw Sunday hats the Flyaway Hats and would do her best to ensure that hers did; even Wilfrid, the kind and gentle one, had such a terrible fight with a nursemaid over the washing of his neck that blood was drawn. Rosslyn was first expelled from school at six for lifting the lady teachers’ skirts: ‘I only wanted to see if they had legs,’ he explained. Later he made a habit of getting expelled, largely because he insisted on keeping his animals with him at all times. This habit stayed with him all his life: as a full-grown clergyman he would preach with a lemur peeping out of his pocket; produce a grass-snake in Sunday School to illustrate the story of Adam and Eve (prompting one small pupil to tell his mother that Rev. Bruce kept the devil in his pocket) and unloose a white dove during a sermon on the Holy Spirit. His middle name was Francis, and his nickname d’Assisi.

The young Bruces delighted in tormenting their great-uncle and their governesses. One, a Miss Sandeman, arrived the same day as Rosslyn’s new incubator. (Rosslyn bred mice; in later life his ambition was to breed green ones. It took him fifty generations, he claimed, and was reported in the Daily Sketch. He also bred a terrier for Queen Victoria, when he was six.) The children decided to exchange their names, and the height of their success was when their great-uncle came into the schoolroom and said ‘Good morning, Miss Incubator.’ They used to hide from her and tease her: ‘She, poor soul, suffered much, and was powerless,’ admitted Podge. Another was a Presbyterian but agreed to take them to their (Episcopalian) church: ‘We knew she would know nothing of the service so we made up our minds to astonish her with every form of ritual we could imagine, finally arranging that at the second last prayer (St. Chrysostom) we should kneel with our backs to the altar …’ Kathleen had a black velvet dress (they spent a lot of time in mourning, for their mother, their father, their grandfather, their uncle the Archbishop of York) which was very stiff and would stand up on its own; Podge would sit it up on the bed with shoes and stockings dangling and invite Bertha the maid to come and have hysterics at the sight of Kathleen’s headless body.

The highest mark they could get for schoolwork was 3; if they got enough 3s they would have a treat. Feeling that the 3s were not coming fast enough, Podge and Kathleen stole their mark books and took them to the Botanical Gardens with a pencil and an India rubber, where Podge practiced and practiced to form a 3 like Miss Incubator’s, and then awarded 3s wherever the children felt they were deserved. The ruse was not discovered, and Podge claimed that she wrote her 3s like Miss Incubator’s till the end of her days.

When they started school Podge used to play truant regularly; she would lurk in the ‘Botans’ and when spotted (one of her brothers told on her) she claimed she had gone in there to do up her petticoat. In the end she and Kathleen both were hauled up before the curator of the Botans for consistently breaking rules—they had a running feud with the head gardener there, Foxy—but managed to get off because Great-Uncle William was a friend of the curator. They used to fiddle the accounts for their schoolbook buying in order to have more money for sweets, and at one school at least children were warned against ‘those awful Bruce girls’.

In a religious Victorian family all this naughtiness should have been more serious than it might be considered today, but there really was nobody to keep track of all of them. Elma, who had become what Kathleen described as ‘rather unwholesomely religious’, perhaps on account of her responsibilities, certainly tried, but she could not always succeed. She took her small siblings on religious retreats, which simply made them naughtier. She would listen to them read their collects every Sunday, and ask them questions. ‘Who was David?’ she asked Kathleen. ‘A ma..a..a..n,’ replied Kathleen, irritatingly if accurately. ‘Well, did you think I thought he was a pig?’ Elma snapped. She also tried to make Kathleen eat mutton fat; Kathleen just developed a technique of hiding it in her pocket. ‘Kathleen has got quite sensible about her food now,’ Elma would say. ‘These things, of course, only need a strong hand.’ Kathleen, meanwhile, was slyly dropping little packets of mutton fat in the gutters of the streets of Edinburgh.

Great-Uncle William had poor sight: he didn’t notice when they used a red-hot poker to brand numbers on the backs of a set of polished mahogany chairs (the chairs were being pupils in the children’s school, and they needed to be able to tell them apart, so they knew which one had taken its turn at reading, and which one was due to spell). There was an ancient chest, a family heirloom through the Skenes, which had belonged to Bonnie Prince Charlie: the little girls labeled each drawer of it with the names of their dolls, and on one occasion cut a piece of cloth off the old kilt that lived in the secret drawer to make a plaid for their doll Gerald. The kilt too had belonged to Prince Charlie, he’d worn it on his escape to the Isles, or so it was said. Uncle William never noticed any of these things. He didn’t even always notice whether or not the plates were in place when he dished out the stewed prunes, much to the children’s delight. He was not a fool about the children, though. When they waylaid the serving staff, hijacked their uniforms and served dinner to the grown ups Uncle William would never quite let on whether or not he had noticed.

On one occasion while Elma was away Podge devised a way of missing church. Uncle William asked her if she would like to be punished now or wait for Elma to return; Podge was scared enough to prefer to wait for Elma. In fact Uncle William was not strict. There was a tawse in the house, but it was more often used on him in play than it was on the children. Podge had merely been infected with something of Kathleen’s fear of men.

Although later in life Kathleen would say that she had only ever been interested in male creatures, this was not true. She recalled herself having had girl dolls, but having ‘put all kindly but firmly to bed with measles. So, through life, let all females be kindly and comfortably disposed of, so that my complete preoccupation with the male of the moment be unhampered!’ Her boy doll (Gerald—he of the plaid), ‘a sailor boy with blue eyes and brown curls’, went ‘everywhere with me’, and was ‘my idol, my baby, my love’, so Kathleen recalled. Podge, on the other hand, clearly recalls a small Kathleen trailing her beloved girl doll Rosie around. Certainly Kathleen, however she may have seen herself, was not one to dispose of women. Far from it: she spent plenty of her adult time delivering babies, caring for their mothers and looking after her female friends in trouble. At this stage she did not like men at all.

When she was quite small she had a frightening experience on the way home from school—a ‘drunken ruffian’ grabbed her on the street and tried to make off with her. Presh ran after to try and kick him, but by then Kathleen had bitten him hard on the hand and made her escape. Podge was more horrified by the idea of biting someone so dirty; but for Kathleen it was the root of a fear of men, which lasted into her teens, and of a lifelong distaste for alcohol and its effects. ‘Should someone lurch, or the slightest bias appear in his gait, my blood ran cold with terror,’ she said. Her later line was more sophisticated: ‘A man is disreputable who can deliberately risk losing his self-control in public.’

In Edinburgh at that time it was very difficult to avoid drunks, and perhaps Kathleen imagined that all men were likely to behave in a frightening and drunken fashion. Certainly when she was seven and their uncle took them all aside to tell them that he had bad news for them, she and Podge both assumed that he was going to prison. Kathleen quite expected that any man might have to go to prison at any time, being as they were the embodiment of evil. In fact the bad news on that occasion was the death of their father.

The Canon had tried hard to put things in order for his children before he died, but, as he wrote to William three months before his death, knowing that he had not long to go: ‘I have no notion what my young ones are to do by and by, unless the Mrs. (who is in Sheffield and very poorly) takes them under her protection more or less… Before she went abroad she very positively declared she would have nothing to say to any of them…’ He was buried beside Janie at Carlton, and Rosslyn had a ferret in his pocket for the funeral. Mrs. Parker continued to have nothing to say to them, but she made good some years later when she paid for Roslyn to go to Oxford (where, legend claims, he kept a baby elephant, because the rule of Worcester College was ‘no dogs’).

When Kathleen was about twelve another frightening man appeared in her life: her cousin Willie. He stayed at Inverleith Row for about a year, and he was old enough to have a latchkey, and wicked enough to stay out at night after the front door had been double-locked. Kathleen’s bedroom was on the ground floor overlooking the garden, and Willie would tap at her window in the small hours, demanding entrance. She would have to creep in silence across the dark dining room and the cold marble-floored hall, and silently unlock the door for him. ‘The rage of the young man was terrifying if the bolt, bar or chain made the slightest sound. More strange and terrifying was he when in the dark and silence he would be ingratiating and affectionate.’ Kathleen feared, hated and adored him in equal proportions. He would do an alarming impersonation of a hunchback and tell her it was useful in avoiding the police. ‘Neither then nor when I grew up did I have the faintest notion why he wanted to avoid the police… I thought it meant that he was some unthinkable evildoer.’ What form his ingratiating affection in the dark hallway took is unknown, but whether out of fear or loyalty she never betrayed him.

Presh had rather more of a secret relationship with Willie. They became friends during the year he spent in Edinburgh, and after he went back to his own family (Janie’s elder brother Felix Skene, a clerk in the House of Lords, was his father) in London they wrote to each other. In one of his letters, he wrote:

Hotel des Iles Britanniques