По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

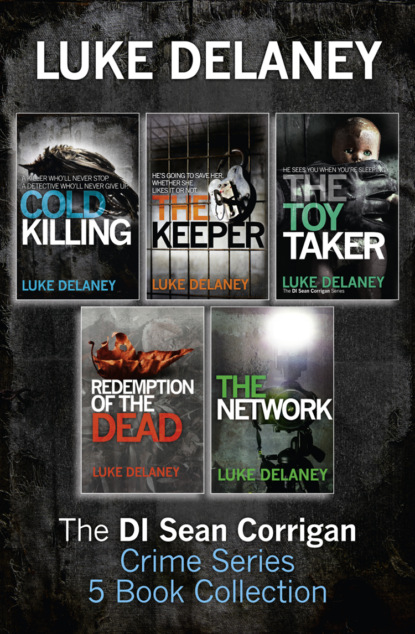

DI Sean Corrigan Crime Series: 5-Book Collection: Cold Killing, Redemption of the Dead, The Keeper, The Network and The Toy Taker

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Korsakov. Stefan Korsakov.’

The constable began to move alongside the metal filing cabinets, which were just big enough to hold the old intelligence cards. As he did, he spoke to himself: ‘K, K, K, K … here we are.’ He stopped and opened the cabinet containing records of people whose surname began with K. He fingered through the files.

‘Korsakov. Korsakov. Stefan Korsakov.’ He pulled a thin card from the cabinet. ‘You’re in luck. We kept his card.’ His smile soon turned to a frown. ‘Bloody typical.’

‘Problem?’ Sally asked.

‘The photographs. They’re not here. Some bastard’s taken the lot.’

‘Did I kill Daniel Graydon? No, Inspector, I didn’t. No matter how hard you find that to believe, it’s the truth.’ Hellier’s eyes were giving nothing away. Damn, he was difficult to read.

‘Why did you lie to us?’ Sean asked. ‘You told us you were never in Daniel Graydon’s flat, which leaves me very confused as to how your fingerprint ended up on the underside of his bathroom door handle.’

Hellier sighed. ‘I lied to you, and that was wrong. I was foolish to do so and I can only apologize for wasting your time. I pray to God I haven’t distracted you from catching the person responsible.’

Sean didn’t believe a word.

‘I have been to Daniel’s flat. I was a client of his. I’ve been so for the past four or five months.’

‘And on the night he died?’ Sean asked.

‘No. I didn’t see him the night he was killed. I didn’t go to his flat that night. I hadn’t been to his flat for over a week.’

‘You see,’ Sean said, ‘whoever killed Daniel got into his flat without breaking in. We believe Daniel let them in. Now what sort of person would Daniel let into his flat at three in the morning? A friend, perhaps? Or maybe …’ Sean paused a second to make sure he still held Hellier’s gaze ‘… a client? One who made regular visits. One he thought he could trust.’

Templeman could stay silent no longer. ‘These questions are totally hypothetical. If you have evidence …’

Hellier put a hand on Templeman’s forearm. Templeman fell silent. ‘I want to answer their questions. Any questions. I didn’t go to his flat that night.’

‘So why did you lie about never having been to Daniel’s flat? You knew this was a murder investigation. You must have known the serious consequences of lying to us. You’re not a stupid man.’

Hellier looked at the floor and spoke. ‘Shame, Inspector. I don’t expect you to understand. I only wish you could.’

Sean had had about all he could stomach. Most of his childhood he’d felt nothing but shame. Shame and fear. Listening to Hellier’s false pleadings made him feel physically sick.

‘You live a lie. You lie to your wife, kids, family, friends. You pay young men to have sex with you and then curl up in bed with your wife. You lie to the police, even though you know that may delay our investigation. And now you want me to believe you lied because you were ashamed of your sexual preferences. I doubt you’ve ever been ashamed of anything in your entire life.’

Hellier looked up from the floor. His eyes were glassy. ‘You’re wrong, Inspector. I am ashamed. Ashamed of it all. I’m ashamed of my life.’

Sean studied him for a few seconds, looking deep into the darkness that he knew seethed behind Hellier’s eyes. ‘So what was so special about Daniel?’ He wanted to keep it personal. ‘Why keep going back to the same boy?’ He used the word ‘boy’ deliberately.

‘I have needs. Daniel helped me with those needs.’

‘Enlighten me.’

‘I practise sado-masochistic sex. So did Daniel. I went to him for that. I generally saw him once every two to three weeks. That’s what I was trying to hide. I was a fool, I know.’

‘What did this practiceinvolve?’ Sean asked.

‘That’s hardly relevant,’ Templeman interjected.

‘There are unexplained marks on the victim’s body. Mr Hellier’s sexual behaviour may explain those marks. It’s relevant.’

‘Nothing too shocking,’ Hellier answered. ‘I would tie him up, by the wrists usually. With rope. We used blindfolds, sometimes whips. Mainly it was role-playing. Harmless, but not something I wanted the world to know about.’

‘I can understand that,’ Donnelly said.

‘Did he ever tie you up?’ Sean asked.

‘No. Never.’

‘So when you say sado-masochistic, you filled the sadist’s role, yes?’

‘Not always. Daniel would beat me sometimes, but I never felt comfortable being in bondage. Daniel said I lacked confidence. He was probably right.’

Hellier had an answer for everything. Sean dropped the address book on the table. It was still in the plastic evidence bag. ‘What’s this?’ he asked.

‘An address book,’ Hellier answered. ‘Obviously.’

‘It was pretty well hidden for an address book. No names either, just initials and numbers.’

‘It contains certain contacts of mine I would rather my wife and family didn’t know about.’ It was an answer that made sense. Like all his answers.

‘Is Daniel’s number in here?’ Sean asked.

Hellier hesitated. Sean noticed it. ‘No.’

Why would that be, Sean wondered. Here was his secret book, yet one of his biggest secrets wasn’t in it. That made no sense. ‘You sure his number’s not in here?’

‘Yes,’ Hellier said. ‘His number’s not in there.’

Sean decided to let it go for now, until he understood more. ‘And the cash: I believe it was about fifty thousand in mixed currency, mainly US dollars?’

‘I like to keep a decent amount of cash about. These are uncertain times we live in, Inspector.’

‘And the money spread across the world in various bank accounts belonging to you? Hundreds of thousands, from what we can see.’ Sean knew these questions would get him no further, but they had to be asked.

‘One thing I won’t do, Inspector, is apologize for my wealth. I work hard and I’m well rewarded. Everything I have, I earned. My accounts are in order. I can show you where the money came from and the Inland Revenue can unfortunately vouch I’m telling the truth.’

Sean was getting nowhere and he knew it. He needed to knock Hellier out of his stride – get personal and see how Hellier reacted. ‘Inland Revenue, your account, your job at Butler and Mason – it’s all very top end, isn’t it?’ He noticed a small, involuntary contraction of Hellier’s pupils that disappeared as quickly as it came. ‘And you, in your thousand-pound suits and three-hundred-pound shoes – you’re a polished act, James, I’ll give you that.’

‘I don’t know where you’re going with this,’ Templeman interrupted. ‘It hardly seems relevant or proper.’

Sean ignored him. ‘But underneath that veneer of yours, there’s an angry man, isn’t there, James? So what is it that’s really pissing you off? Come on, James, what is it? What are you trying to hide? A working-class background? Maybe an illegitimate child somewhere? Or did you disgrace yourself in some previous job – got caught with your hand in the cookie jar – everything was smoothed over, but still you were shown the door? Come on, James – what is it you’re hiding from me – from everyone?’

Hellier just stared straight into him, his eyes never blinking, lips sealed tightly shut, possibly the faintest trace of a smirk on his face as his muscles tensed, controlling his facial reactions, making him impossible to read.

‘You know, James,’ Sean continued, ‘you can have it all – the job, the money, the wife and kids, the Georgian house in Islington – but you’ll never really be like them. You’ll never be accepted as one of them, not really. You’ll never be like … like Sebastian Gibran, and you know it.’ Another contraction of Hellier’s pupils told Sean he’d hit a raw nerve. ‘You can try and look like him, even sound like him, but you’ll never be like him. He was born into that role. He’s the genuine article, while you’re a fake – a cheap imitation − and you can’t stand it, can you?’