По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

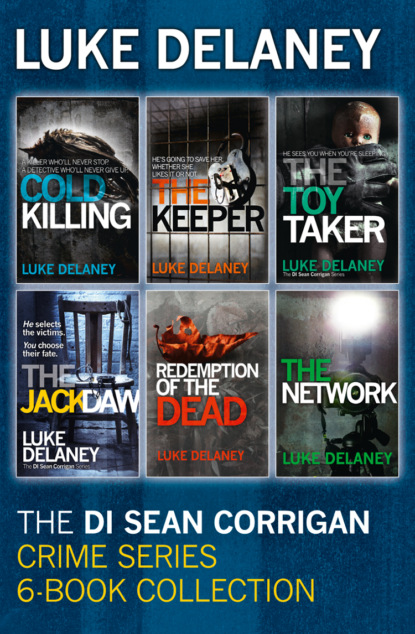

DI Sean Corrigan Crime Series: 6-Book Collection: Cold Killing, Redemption of the Dead, The Keeper, The Network, The Toy Taker and The Jackdaw

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Well, Sally?’

‘Fingerprints,’ she said. ‘Missing fingerprints.’ She studied him for a reaction. Maybe a hint of confusion, but nothing more. ‘Back in ninety-nine, you took a set of fingerprints out of the Yard.’

‘Ninety-nine?’ Wright protested. ‘I don’t think I’ll be able to remember back that far. Whose prints were they?’

‘Stefan Korsakov’s,’ she answered. Wright flushed a little. She noticed it. ‘You remember?’

‘Sure,’ he replied. ‘I remember.’

‘How come? It was a long time ago.’

‘Because I helped put the bastard away. If you’re here to tell me he’s dead, then you’ll make me a happy man.’

‘Maybe he is,’ said Sally. ‘We’re trying to find that out. But for now, you remember taking the prints out of the Yard?’

‘Yeah. And I remember taking them back just as clearly.’

Sally picked up the speed of the questions. ‘Why did you pull them out in the first place?’

‘I was doing someone a favour. The prints weren’t for me.’

‘Who were they for?’

‘Paul Jarratt. He was a DS at Richmond at the time. I was still a DC. We worked the Korsakov case together. He asked me to pull the prints, so I did.’

‘Did he say why he wanted them?’

‘I can’t remember. Maybe he said the Prison Service had asked for them, but I’m not sure. All I know is that if someone has lost his prints, it wasn’t me. If you want to know why DS Jarratt needed the prints then perhaps you should ask him.’

‘You know what?’ Sally told him. ‘I think I’ll do exactly that.’

The phone was ringing on Hellier’s desk as he entered his office. He closed the door before answering.

‘Hello. James Hellier speaking.’

‘Mr Hellier,’ the voice on the other end began. ‘I hope you don’t mind me calling you at work. It was the only way I could think of contacting you.’

The voice belonged to a man. He sounded mature, in his forties perhaps. He spoke quite well. Hellier could hear no trace of an accent. He didn’t recognize the voice, but suspected it was being artificially disguised. It sounded concerned. He could sense no harmful intent, but was as cautious as ever.

‘You’re not a journalist, are you?’ Hellier barked the question. ‘Because if you are, I’ll find out who you work for and by this evening you’ll be looking for a new job that you won’t find.’

‘No. No.’ The man’s voice was slightly pleading. Hellier still sensed no threat.

‘Then who are you?’

‘A friend,’ the man answered. ‘A friend who knew Daniel Graydon. And now … now I’d like to become your friend. A friend who can help you.’

Hellier said nothing.

‘Listen to these instructions. Follow them exactly if you want to meet me, but be careful. Your enemies are everywhere.’

Hellier listened hard to the instructions, memorizing every detail. When the voice had finished, the phone line went dead. Hellier sat in silence with the phone pressed to his ear. His new friend had to be a journalist. He wouldn’t put it past Corrigan to have put the vermin on to him in the first place, trying to panic him into making a mistake, but it wouldn’t work. He knew how to deal with journalists and he knew how to deal with Corrigan. After a minute or two he was brought back to the world by a knock at his door.

‘Come in,’ he said, his voice a little hoarse. The door opened as Sebastian Gibran let himself in and pulled a chair close to Hellier’s desk. Hellier found himself leaning back, as far away from Gibran as he could.

‘Thought I’d see how you were. See how things were going with the police. Make sure you were okay. Nothing getting on top of you too much?’

‘I’m fine, thank you, Sebastian. Despite everything, I seem to be bearing up.’ Hellier found it harder than usual to play the corporate game. The voice on the telephone had been an unwelcome complication.

‘Good. I knew it would take more than jealous allegations to upset a man like you.’

‘Jealous allegations?’

‘Of course. People will always be jealous of people like us. They want what we have, but they’re never going to have it. It’s not just wealth, it’s everything. They can win their millions on the lottery as much as they like, but they’ll never be like us. Never walk amongst other men as we can, safe in the comfort of our own superiority. It’s our right. You do understand, don’t you, James?’

‘A king will always be a king. A peasant will always be a peasant.’

‘Exactly.’ Gibran beamed. ‘That’s why I brought you to this firm in the first place, James, because I knew you had what it takes. When I first spoke to you at that conference all those years ago, I knew. I’d met hundreds of financial superstars that week, but I knew you were different. I knew you belonged here at Butler and Mason – and I made damn certain I got you.’

‘I’m forever grateful,’ Hellier managed, but he was a little disturbed by this side of Gibran he’d never seen before − the perfect corporate manager and visionary seemingly replaced by a more arrogant, self-serving elitist. Was he finally meeting the real Sebastian Gibran − or was Gibran trying to trick him into lowering his guard, looking for a reason to move him on to pastures far less green?

‘Any gratitude owed has already been repaid,’ Gibran told him. ‘You know, James, none of us are immune from making mistakes. The very nature of our business is risk orientated. We accept that people will make bad decisions from time to time. Those decisions will sometimes cost us a great deal of money, but we accept it.’

Hellier listened, trying to predict the moment when the conversation would become specific to him.

‘But other mistakes, errors of judgement not related to work, are less tolerated. The people who own Butler and Mason like to portray a very particular image: they like their employees to be married, settled, and they encourage people to have children by creating a pay structure that rewards a family life. The image of this company has emerged by design, not accident, and they guard it jealously. If an employee has elements in their life that do not fit easily with our company ethos, then they would be expected to bury those …’ Gibran searched for an appropriate word, ‘those habits, where they would never be seen. If they failed to do so, then their position here might not be tenable. If someone was to draw unwanted attention to our business, even if it was by accident, even if it was later shown not to be that person’s fault, the company would nevertheless expect that person to bring that situation to a swift conclusion. We’re all clear on that philosophy, aren’t we, James?’

‘I understand perfectly,’ Hellier answered.

‘Listen,’ Gibran said, his voice and tone suddenly sounding more like the man Hellier recognized. ‘That was the corporate line – make of it what you will. This is from me: watch your back. I can only protect you so much. I like you, James. You’re a good man. Tread carefully, my friend.’

Hellier watched him for a while before answering. ‘I will. Thank you.’

‘As Nietzsche said, “Not mankind, but Superman is the goal … My desire is to bring forth creatures which stand sublimely above the whole species.” That is what we are expected to be, James. The failings of normal men are not a luxury we’re allowed.’

‘“To live beyond good and evil”,’ Hellier continued the quote from Nietzsche.

Gibran leaned slowly forward. ‘I knew we understood each other. You see, James, it’s our imaginations that truly set us apart. Without that, we’d be just like all those other sad fools wandering around soulless, aimless, pointless. Only fit to be ruled over by those fit to rule. That may sound arrogant, but it’s not. It’s reality. It’s the truth.’

Sean entered the press conference room at New Scotland Yard. He walked behind Superintendent Featherstone, who would head the conference. Sean was only there to deal with specifics, not the general presentation.

Other than the TV people there were about a dozen journalists there. A lot less than there would be for a celebrity or child murder, but more than there would have been for a run-of-the-mill killing. Most of them had been following the case since Hellier’s initial arrest, when Donnelly had leaked it to a contact in the media.

Featherstone introduced them and outlined the details of Daniel Graydon’s murder. He began to tell the journalists what the police wanted from the public. Sally would repeat it later that night on Crimewatch.

‘We’re appealing to anyone who may have seen Daniel meet someone outside Utopia nightclub that night. Perhaps a cab driver who took Daniel home. A friend or acquaintance who maybe gave him a lift,’ Featherstone explained.

‘We are also interested in anyone who may have heard or seen something later that night, close to Daniel’s flat in New Cross. Did anyone see a man acting strangely in the area? Again, maybe the man responsible for this terrible crime used a cab to leave the area. Can anyone remember picking up a passenger in the early hours? Someone who aroused their suspicions?’