По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

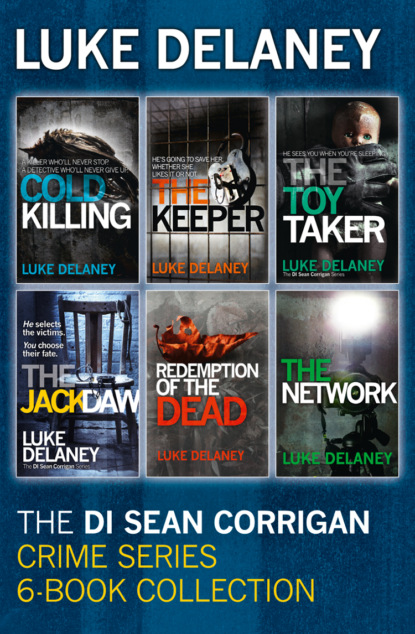

DI Sean Corrigan Crime Series: 6-Book Collection: Cold Killing, Redemption of the Dead, The Keeper, The Network, The Toy Taker and The Jackdaw

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Plenty of time to deal with him later,’ said Sean. ‘I take it I have you to thank for the cavalry turning up?’ Donnelly waved his mobile by way of an answer, but Sean was already searching through the cabinet next to Sally’s bed.

‘Looking for something?’ Donnelly asked.

‘Sally’s personal stuff,’ Sean answered.

‘Why?’

‘I need it. I need to make sure.’

‘Of what?’ Donnelly enquired.

‘That Gibran goes down for what he did to her.’ Sean nodded towards Sally.

‘Her personal stuff’s probably locked up and logged.’

‘Not necessarily. She came in through A and E, remember. They had better things to do than worry about bagging and tagging property.’

He pulled the bottom door open and saw what he’d been praying for: a plastic bag containing Sally’s personal items. Her simple watch, some jewellery, even an elastic headband and the thing Sean sought most – her warrant card.

‘Is the bag sealed?’ Donnelly asked in hushed tones.

‘No,’ Sean almost whispered the answer. ‘Her warrant card’s in its own bag, but it’s not sealed.’ Sean held the bloodstained police identification gently in his uninjured hand. He knew what he had to do.

‘This needs to be found in Gibran’s home when it’s searched,’ he told Donnelly.

‘I understand,’ Donnelly assured him.

‘It’s best if you don’t find it yourself. Leave it for one of the other searching officers to find. Understand?’

‘Perfectly, guv. Leave it to me.’

‘You’re a good man, Dave.’

‘I know,’ was Donnelly’s only reply.

Gibran sat impassively, his hands resting unnaturally on the table in front of him. Sean and Donnelly sat opposite. There was no one else in the interview room. Sean hadn’t been surprised when Gibran waived his right to have a solicitor present. He was far too arrogant to believe anyone could protect him better than he could himself.

Sean completed the introductions and reminded Gibran of his rights. Gibran politely acknowledged everything Sean asked him.

‘Mr Gibran, do you know why you’re here?’ Sean asked.

Gibran ignored the question. ‘I’ve never been inside a police station before,’ he said. ‘It’s not quite how I imagined it. Lighter, more sterile, not as threatening as I thought it would be.’

‘Do you know why you’re here?’ Sean repeated.

‘Yes, I understand perfectly, thank you.’ Gibran smiled gently, untroubled, at peace with himself.

‘Then you know you’re accused of several murders, including the murder of one police officer and the attempted murder of another?’

‘I am aware of my situation, Inspector.’

‘Yes,’ Sean continued. ‘Why don’t we talk about your situation, Mr Gibran?’

‘Please, call me Sebastian.’

‘Okay, Sebastian. Do you want to talk about the things you’ve done?’

‘You mean the things I’m accused of doing.’

‘Are you denying that you killed Daniel Graydon? Heather Freeman? Linda Kotler? Police Constable Kevin O’Connor? Are you denying you tried to kill Detective Sergeant Jones?’

‘What is it you want, Inspector?’ Gibran asked. ‘A nice neat confession? For me to tell you where, how and why?’

‘Ideally,’ admitted Sean.

‘Why?’

‘So I can understand why those people died. So I can understand why you killed them.’

‘And why is it you want to understand those things?’

‘It’s my job.’

‘No,’ Gibran said, still smiling slightly. ‘That’s too simple a reason.’

‘Then why do I want to know?’ Sean risked asking for Gibran’s opinion.

‘Fear,’ Gibran answered. ‘Because we fear what we do not understand. So we label everything: a nice, neat explanation hanging around a murderer’s neck. He killed because he loved. He killed because he hated. He killed because he’s schizophrenic. The labels take away the fear.’

‘Then what should we put on your label?’ Sean asked.

Gibran’s smile grew wider as he leaned back from the table. ‘Why don’t we just leave it blank,’ he answered. ‘It would be so much more interesting, don’t you agree?’

‘It won’t help you in court,’ Sean reminded him. ‘Life imprisonment doesn’t have to mean life.’

‘I understand you’re trying to help me, Inspector, but from what I can tell, you’re a long way from convicting me of anything.’

‘You will be convicted,’ Sean assured him. ‘Be in no doubt of that.’

‘You sound very sure of an unsure thing,’ Gibran said. ‘But I’ll make you a deal. If I’m convicted of these crimes, then we’ll talk again, maybe in more detail. If your evidence fails you and I walk away a free man, then we shall never discuss the matter again.’

‘Confessions after conviction are worth nothing,’ Sean told him.

‘Maybe not to the court, but to you it would be worth a great deal, I believe.’

Sean sensed Gibran was trying to end the interview. Was he tiring? The effort of attempting to appear sane and polite exhausting him? Sean had to keep going.

‘Tell me about yourself,’ he said. ‘Tell me about Sebastian Gibran.’