По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

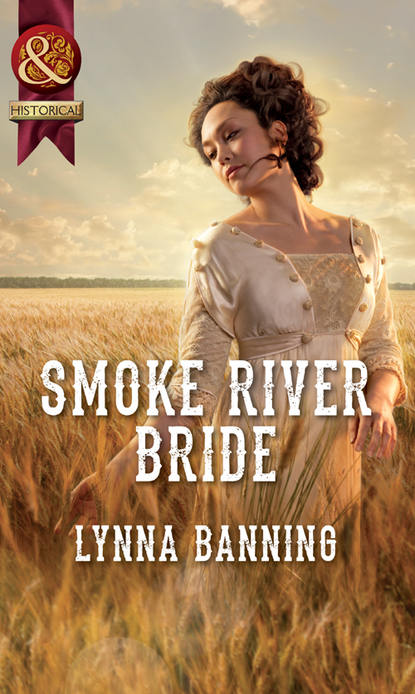

Smoke River Bride

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Go to sleep? “Are you not going to—?”

“Nope,” he said. “We’re married, but we don’t hardly know each other. Let’s give it some time.”

Leah rolled onto her back and lay staring up at the ceiling. Thad MacAllister was a most unusual man.

Or perhaps he does not like me.

But then he laid his arm across her waist and gently nudged her closer. Her silk-clad shoulder and hip brushed against his skin and his warmth enveloped her like a fine wool robe.

“You sure feel warm,” he murmured. “I’ve been kinda cold for a while.”

Leah smiled into the dark. It was a good beginning.

Chapter Seven

Before dawn, Leah awoke and snuggled into the space where Thad had lain until a few moments ago. It was still warm and it smelled like him, a mixture of pine trees and sweat. She liked it. She liked him.

She thanked the gods of good fortune for finding this man, for allowing her to take this step—safe and protected—into a new life.

She glanced at the bedroom window where faint gray light was beginning to filter in. He must have left before dawn—to do what? She knew farm chores waited, scattering feed for the chickens and gathering eggs, feeding and watering the horses, milking the black-splotched cow she’d glimpsed in the pasture yesterday. It was the same in China, except that her mother had milked a nanny goat. What would Thad expect her to do?

Fix his breakfast! She scooted out of bed, hung the pink silk night robe on one of the hooks that marched across the wall beside the bedroom door, and pulled on the jeans and red shirt she had worn yesterday. The stiff denim fabric scratched her inner thighs and the pointy shirt collar jabbed her neck whenever She turned her head.

How uncomfortable these American garments were! She longed for the silky feel of her Chinese-style tunic against her skin and the soft folds of the loose trousers.

The kitchen was as spotless as she had left it and, to her surprise, a fire already crackled in the stove; Thad must have uncovered the banked coals and added more wood. He had even set the large tin teakettle on the back burner. That must be a hint that he expected coffee with his breakfast.

But what to cook? The few American breakfasts she had seen on board the ship from China consisted of charred meat and a pan of something messy—eggs, she guessed—mixed up into a dreadful-looking yellow pile. She had eaten eggs in China, but they were boiled in the shell and shiny as a full moon.

In the small pantry just off the kitchen, she found the bag of coffee beans and a basket of fresh eggs. On a shelf sat a pretty red-painted box with an iron handle and a tiny drawer that pulled out. That box had not been there yesterday.

Oh! For the coffee beans! You were supposed to grind them up before…

Hurriedly she gathered up four fresh eggs, covered them with water pumped from the sink and set the pot on the stove next to the teakettle.

“Aint’cha gonna make biscuits?” The querulous voice came from the loft, where Teddy balanced on the ladder, one elbow hooked around the railing.

“Biscuits?”

“You know, like little muffins, only they’re not sweet.” He surveyed her with disgust. “You don’t know anything, do ya?”

Leah straightened. “I know a great many things, Teddy. However, I grew up in China and I did not learn to cook in the American way.”

“Ya want me to mix up some biscuits? I know how ’cuz Marshal Johnson showed me once, but Pa won’t let me do it.” He clattered to the bottom rung of the ladder.

Leah grabbed a crockery mixing bowl and shoved it toward the boy. “Yes, please. Show me how it is done.”

Teddy puffed out his chest, took the bowl and disappeared into the pantry. “This here’s flour,” he announced when he emerged. “And then ya add a pinch of saler’tus. Now you dump in a spoonful of bacon grease and a bit of milk, and then you squish it all together, like this.” He plunged both hands into the bowl.

Leah nodded, committing the ingredients to memory while Teddy scooped up the mixture, dropped large lumps onto a tin baking sheet and shoved it into the oven.

“Don’t tell Pa I made ’em, okay?”

“Okay. Do not tell your father that I did not know how.” A conspiratorial look passed between them. Merciful heaven, perhaps the boy would grow to not hate her.

The back door thumped open and Thad tramped in, a milk pail in one hand and a basket of eggs in the other. He clunked both pail and basket in the pantry and strode into the kitchen.

“Mornin’, Pa.”

Thad ignored the boy. “Breakfast about ready?” His breath puffed white from the cold air outside. Carefully he avoided eye contact with Leah.

“Almost, yes.” She opened her mouth to comment on his brusque manner toward his son, then changed her mind. Not in front of Teddy, she resolved. Any differences between her and her husband would not be aired within his son’s hearing.

“I’ll go wash up at the pump outside.”

“Do you not wish to bathe in warm water? I can heat—”

“Bathe! I take a bath once a week, on Saturday.”

“Me, too,” Teddy added. “Pa, she’s so dumb she doesn’t even know how to make coffee.”

Leah flinched. She’d been right the first time—Teddy did hate her. But Thad wasn’t listening, and besides, this morning she had puzzled out the mysteries of the American brew and used the coffee grinder.

The back door slammed. Teddy fled up to his loft, leaving Leah, her teeth gritted, to set the table and check the biscuits.

Thad clunked back into the kitchen, his heavy boots slathered with mud, and plopped himself into one of the ladder-back chairs. Teddy slid onto the other, but Thad motioned him away. “That’s for Leah.”

Then he looked down at his breakfast. Two shiny white whole eggs stared up at him.

“What’s this?”

“Eggs,” Leah said quickly.

“And biscuits,” Teddy piped. Leah set a napkin-covered bowl on the table.

“Try a biscuit, Pa.”

“Soon as I figure out this egg thing on my plate.” He sent a questioning look to Leah, who settled herself at the table and picked up her boiled egg. “In China, we do it like this.” She lifted a spoon and gently tapped around the middle until a crack appeared, then adroitly split the egg into two parts and scooped out the inside with her spoon.

Teddy scowled down at his plate. “People in China are stupid.”

“Eating an egg with a spoon like this is not stupid,” Leah countered in a quiet voice. “It is merely different.”

“And it’s dumb, too,” the boy retorted.

“Teddy,” Thad warned. He noticed suddenly that his son’s hair was uncombed and that Leah wore the jeans and shirt from the mercantile. Her feet were encased in the same satin slippers she’d worn yesterday. She’d need a pair of boots, too.

Absently he reached for a hot biscuit. “What size boot do you wear, son?”