По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

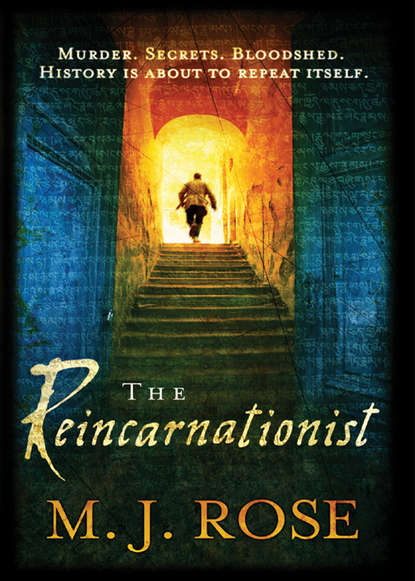

The Reincarnationist

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Now he could see the man’s features. This was no homeless drunk; this was Claudius, one of the young priests from the college. And his eyes had been gouged out in a final ritualistic indignity.

Julius realized what Claudius was holding in his hands: not food, but the poor soul’s own eyes.

How much suffering had been inflicted on this man, and why? Julius stumbled backward. The emperor’s endless thirst for power? What made it worse was that the people doing the man’s bidding didn’t realize he was using them and that no god was speaking through him.

“Get away. Go now,” a voice whispered.

It took several seconds for Julius to find the old woman hiding in the shadows, staring at him, the whites of her eyes gleaming, a sick smile on her lips.

“I’ve been telling you. All of you. But no one listens,” she said in a scratchy voice that sounded as if it had been rubbed raw. “Now it starts. And this—” she pointed a long arthritic finger toward the direction Julius had just come from “—is just the beginning.”

It was one of the old crones who foretold the future and begged for coins in the Circus Maximus. For as long he could remember she had been a fixture there. But she wasn’t offering a prediction now. This was no mystical divination. She knew. He did, too. The worst that they had feared was upon them.

Julius threw her a coin, gave Claudius a last look and took off.

Not until he passed through the city’s gates an hour and a half later did his breathing relax. He straightened up, not aware till that minute that he’d been hunched over, half in hiding. Always half in hiding now.

Throughout history, men fought about whose religion was the right one. But hadn’t many civilizations prospered and thrived side by side while each obeyed entirely different entities? Hadn’t his own religion operated like that for more than a thousand years? Their beliefs in and worship of multiple gods and goddesses and of nature itself didn’t preclude the belief in an all-powerful deity. Nor did they expect everyone else to believe as they did. But the emperor did.

The more Julius studied history the more it became clear to him that what they were facing was one man using good men with good beliefs to enhance his own authority and wealth. What had been proclaimed in Nicaea almost seventy-five years ago—that all men were to convert to Christianity and believe in One God, the Father Almighty, Maker of Heaven and Earth—had never been enforced as brutally as it was being enforced here now. The killings were bloody warnings that everyone must conform or risk annihilation.

Julius and his colleagues weren’t under any delusions. If they intended to survive they needed to abandon their beliefs or at least pretend to do so. And if they were going to continue into the future they needed to relax some of their laws and adapt. But right now they had worse problems. Emperor Theodosius was no holy man; this was not about one god or many gods, not about rites or saviors. How clever Theodosius and his intolerant bishop were! Conspiring to make men believe that unless they adopted the current revised creed, they would not only suffer here in this life but would suffer worse in the next life. The danger to every priest, every cult, everyone who held fast to the old ways, increased daily. The priest he’d seen in the gutter that morning was yet another warning to the rest of the flamen.

Citizens everywhere were taking up the emperor’s call to enforce the new laws, publicly declaring their conversion. But behind closed doors, other conversations took place. The men and women who had prayed to the old gods and goddesses for all of their lives still hoped for a reprieve from the new religious mandate. Yes, in public, they would protect themselves and prove their fealty to their emperor, but as modern as Rome was, it was also a superstitious city. As afraid as the average citizens were of the emperor, they were more afraid of the harm that might befall them if they broke trust with the familiar sacred rituals. So while there was outward acquiescence, even energy for a religious revolution, much of it was false piety.

But for how much longer?

The old ways would die a little more with every priest who was murdered and with every temple that was looted and destroyed until there was nothing left and no one to remember.

The trunks of the lofty trees were gnarled and scratched, the boughs heavy with leaves. The forest was so thick the light only broke through in narrow shafts, illuminating a single branch of glossy emerald leaves here and a patch of moss-covered ground there.

There were myrtle trees, cypress and luxuriant laurels, but it was the oaks that made this a sacred grove, an ancient place apart from the everyday world where the priests could perform their rituals and pray to their goddess.

He sat down on a mossy rock to wait for Sabina. There, miles outside of the city gates, he couldn’t hear the sounds of soldiers training or citizens arguing or chariots rolling by. He couldn’t smell the fear or see the sadness in people’s eyes—ordinary people who didn’t understand politics and were frightened. In the grove there was only birdsong and the splashing of water that fell from between the cracks in the rocks into the pool below. The consecrated area stretched deep into the woods, and no matter how often Julius went there, he never felt as if he saw it all or understood the mysteries that it contained. Nothing there was commonplace. Every tree was a sculptural arrangement of boughs branching off into more boughs, with more leaves than any man could count, all shimmering in a light that was always softer and gentler here than anywhere else in Rome. Every patch of ground offered a bounty of sprouting grasses, moss, shade plants and flowers.

When he was a boy, his teachers told the story of how this grove was where Diana, the goddess of fertility, assisted by her priest, had performed her duties. The King and Queen of the Wood, they were called. Bound together in a marriage, they made spring buds give way to summer flowers and then to fall fruits.

The boys snickered, glancing at each other, making up stories about what else they did up there, all alone in the woods. Joking about the bacchanals that must have gone on in the grove—sacred or not—because they all knew what men did with other men and with women. It was not secret, it was not profane.

Only the Vestal Virgins were sacred. Vestals promised a vow of chastity during their term of service and in exchange were ranked above all other Roman women and many men. Powerful, on their own, free in so many ways, they were not bound by the shackles of motherhood or the rules of men.

In exchange for that power and importance, each woman gave up her chance of a physical life with a man until after she had served for thirty years: the first decade learning, the second serving as a high priestess and the third teaching the next generation. Some thought it was a lot to ask of a woman; others didn’t agree. From the time she was six, or eight or ten, until the time she was thirty-six or thirty-eight or forty, she remained chaste. Never to feel a man’s hand on her skin or suffer the pressure between her legs that was natural and good. Never give in to the hot eyes of the men who came to her as a priestess but saw through the veils to the woman. Because if she did give in, if she lost her fight with virtue, there was no leniency. The punishment was grave and unrelenting. She was buried alive. It was harsh. But the Vestals were sacrosanct. And only a small percentage broke her vows.

Occasionally a nobleman did get away with seducing a Vestal. Hadrian had stolen one and made her his wife, and nothing had happened to either of them, but throughout history, as of that day in the grove, of the twenty-one Vestals who had been with a man, seventeen had been buried alive and fifteen of the men they had been with had also been put to death. The rules did not bend easily.

Although it was blasphemy and he only let himself think it for a moment, Julius thought that if they adopted the emperor’s new religion, he and Sabina would be allowed to live together openly and without fear. But could they give up everything they believed?

“Julius?”

He heard her before he saw her, and then she stepped into the path of a sunbeam. Red hair almost on fire. White robes glowing. He walked to her, smiling, forgetting for just those few minutes the massacred priest he’d seen that morning and what it portended for their future. Sabina stopped a foot away and they stood apart, looking at each other, drinking each other in.

At last.

“The news in the atrium is bad. Did you know Claudius was killed?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said, but didn’t want to bring the full horror of what he’d seen into the grove.

“What does this mean? Another priest killed?” She shook her head. “No, let’s not talk about this. Not now. There’s time for this conversation later.”

“Yes, there is.”

“How many times have we met here? Fifteen? Twenty?” she asked.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: