По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

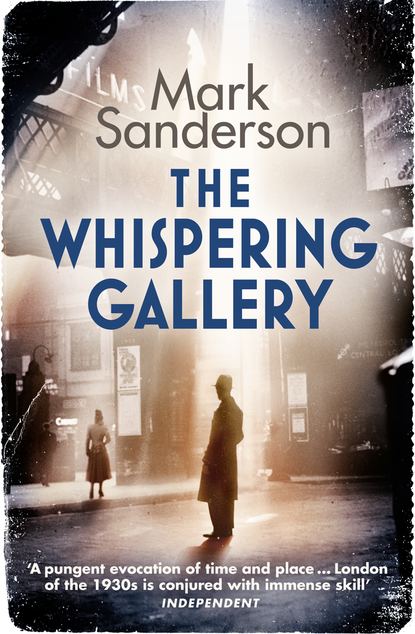

The Whispering Gallery

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Ha, ha, ha, Simkins! Don’t try and deceive this poor woman,” said Simkins. “She’s been through quite enough as it is.” His eyes shone with mischief as he watched Johnny’s already red face get redder.

“Mrs Callingham, this unscrupulous toff is in fact Henry Simkins from the Chronicle.”

Simkins laughed and shook his bare head. His chestnut curls gleamed in the sunlight. They were so long they almost touched his narrow shoulders.

“If you don’t admit who you are this minute I’ll knock the damn truth out of you.” Johnny clenched his fists. He turned to the widow they were fighting over. She must have been about forty years of age. Her almost oriental eyes exuded misery. “This man is an impostor. He wasn’t with your husband when he died. Has he shown you any identification?”

“Leave her alone, Simkins,” said Simkins. “You’re adding to her distress.” He put an arm round her shoulders and tried to shepherd her away. “I must say, Simkins, I find your joke in somewhat poor taste.”

Johnny showed the woman his press card. She studied his photograph.

“It certainly looks like you.” Simkins laughed.

“Where’s yours?”

“I have no need for such fripperies,” sighed Simkins. “Anyone can fake them. Shame on you, Simkins, for trying to dupe this grieving widow.”

Johnny remembered the slip of paper that Father Gillespie had passed on to him. It was worth a go. He retrieved it from the back of his notebook.

“If I wasn’t with your husband, how did I get this?” He thrust it towards her. Simkins read out the proclamation – I love you daddy – and tried to snatch it, but Johnny was too quick for him. “Oh no you don’t, you bastard.”

Mrs Callingham gasped at the coarse epithet.

“I beg your pardon, ma’am. D’you recognise it?”

“Yes, yes I do.” Tears sprang into her eyes once more. “Freddie kept it in his wallet. Daniel gave it to him when he was four – he’s fifteen now.”

Simkins knew the game was up. Before either of them could shower him with recriminations – or worse – he made off towards London Wall.

“See you Friday evening, Steadman. You’ll have a ball, I promise!”

As if he could trust any promise Simkins made. Johnny assumed he must have been invited to the Cave of the Golden Calf as well.

“So you really are Mr Steadman?” She returned the lace handkerchief she was clutching to her handbag. They finally shook hands. “Why was that gentleman pretending to be you?”

“He was intending to hijack your story. Simkins has the morals of a snake. He must have inherited them from his father, who’s a Tory member of parliament.”

“And he chooses to write for the yellow press?” She blushed, realising what she had said. “Excuse me. I meant no offence.”

“None taken.” Johnny was used to being held in low esteem – at least in certain quarters.

“How did he know I wanted to see you?”

“I’m afraid I’m not the only one with connections at Snow Hill. Money loosens most tongues and he’s not averse to using his own to do it. After all, he’s not short of a bob or two.”

They were impeding the constant stream of foot traffic that flowed in and out of the police station.

“We can’t talk properly here. Fancy a cup of tea?”

They walked down to Moorfields and found a café opposite Moorgate Street station. The sound of slamming doors and whistles reached their table through the open windows. Once the harassed waitress had taken their order – Johnny, having skipped breakfast, was starving – Mrs Callingham launched into what was clearly a pre-prepared speech.

“I can’t thank you enough, Mr Steadman, for being there on Saturday. I know you tried your best to help Freddie. If it weren’t for you I’d probably still be tearing my hair out at home.” Her immaculate coiffure gave no sign of being disturbed.

“Call me Johnny.” He waited for her to reveal her own Christian name. She remained silent. He produced his notebook. “Cynthia is your first name, isn’t it?”

“Is it relevant?”

“I can’t keep referring to you as Mrs Callingham in the interview.”

“There isn’t going to be an interview. I merely wanted to express my deep gratitude and find out if Freddie had said anything apart from ‘I’m sorry’.”

“No, he didn’t. Any idea what he was apologising for?”

“I presume it was for injuring the other man. I do hope he didn’t know that he’d gone and killed him.”

“Why don’t you want me to write anything further?”

“I’ve got Daniel to think of. He’s just lost his father. The last thing he needs is a pack of newshounds chasing after him. We require privacy now, not publicity.” A minute ago she’d been grateful for the attention he had created.

“How is your son?”

She looked at him as if it were a stupid question.

“Awfully upset. What did you expect? Daniel’s a very private child, though. He doesn’t talk about his feelings. It’s even an effort to get him to tell me what’s going on at school.”

“Which school is that?”

“St Paul’s.”

Johnny’s antennae quivered. “Bit of a coincidence, isn’t it?”

“Not really. The school is in Hammersmith.”

“It used to be next-door to the cathedral.”

“That was years ago.”

“OK. Have you any idea why your husband was in St Paul’s?”

“None at all.” She waited until the waitress had uncere moniously deposited two cups of tea and a bacon sandwich in front of them. Johnny tucked in straightaway. It gave him time to think. He swallowed the mouthful he was chewing and went on the attack.

“Why did he kill himself?”

“He didn’t!” Her eyes welled up. “He wouldn’t! He’d never do such a thing. He was a religious man. He was a devoted father. Freddie was not the type to deliberately leave us in the lurch.”

“You haven’t found a note then?” He couldn’t see a doctor, no matter how desperate, scribbling Dearest dear . . .

“No.” She pressed her thin lips together firmly. Suicide was a crime – just attempting it could land you in prison. Was she so anxious to avoid the social stigma that she preferred to think her husband may have been murdered?