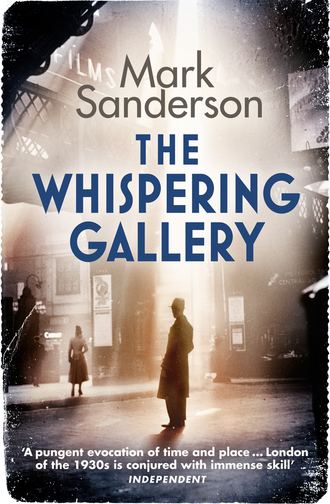

The Whispering Gallery

“OK. In the meantime see what you can find out about the other bloke who died.”

“Graham Yapp.”

“That’s him. It’ll be one way of keeping the story alive. However, your main priority is this morning’s unwanted gift. The detective who turned up was most put out you weren’t here. He gave poor Reg a hard time.”

“What was the chap’s name?”

“Detective Constable George Penterell. I got the impression he hasn’t been in the job long and is keen to make his mark. You better not keep him waiting any longer.”

“Should I show him this?” He got out the postcard of St Anastasia which had arrived on Saturday. “It must have been sent by the same person.”

“You better had,” said Quarles. “You don’t want to be charged with withholding evidence. Beauty is not in the face; beauty is a light in the heart. In my humble opinion that’s both true and untrue. There’s got to be an initial spark of attraction, hasn’t there? Something to make the pupils dilate. Speaking of which: how’s Stella?”

“I wish I knew. She spent the weekend in Brighton, apparently. With a bit of luck I’ll see her tonight – assuming I’m not banged up at Snow Hill.”

Johnny arrived at the police station fully appreciating the meaning of the phrase “muck sweat”. He felt – and smelt – filthy. Usually he was glad of the opportunities his job afforded him to get out and about – after two hours at a desk he was more than restless – but the dog days had left him dog-tired. He was sick of being at everyone’s beck and call, resentful of having to traipse all the way to Snow Hill in the heat. By the time he got there he was out of breath and out of sorts.

“Mr Steadman? Glad to make your acquaintance – again.” They shook hands. “You look like you could do with a glass of water. This way.” DC Penterell towered over him, a smile of amusement playing on his thin lips. Large brown eyes with long lashes looked down on him benevolently. He was a giraffe in a new double-breasted suit.

Somewhat relieved at the unexpectedly polite welcome, Johnny wiped his brow and followed the detective through the swing doors with their bull’s-eye windows and down a corridor painted dark grey below the dado and light grey above it. Penterell showed him into one of six grim interview rooms. Like the others, it contained a battered table, four sturdy chairs and absolutely nothing else.

“Have a seat. I won’t be a moment. Take your jacket off, if you wish.”

Johnny did not need asking twice. He would have liked to take his shoes off as well, but that would have been going too far. His feet were singing.

Fortunately, Penterell had left the door open. He hated being in windowless rooms. Clangs and yells drifted up from the cells below. The single bulb in its enamelled tin shade above him was dazzling.

“I thought you might prefer tea.” The young man was carrying two cups and saucers and a glass of water on a tray. Not a drop had spilled. What next? An invitation to lunch? There was a brown cardboard folder under his right arm.

Johnny emptied the glass in one go. “Thank you.”

“What was so important this morning that you couldn’t wait for me?” The large brown eyes hardened. Johnny felt the chair press into his clammy back.

“Another story. I was at St Paul’s when the chap fell to his death on Saturday.”

“Fell?”

“Fell or jumped. You tell me.”

“It’s not my case. I’m only interested in the owner of the arm that landed on your desk this morning.”

“Anybody reported one missing?”

“We wouldn’t be sitting here if they had.”

“Am I your only lead then?”

“More or less . . . Which is why it would have been useful to speak to you earlier.”

“A couple of hours hasn’t made any difference. The lack of blood suggests the arm – I’m assuming it was real – must have come from a dead person.”

“Your assumption is correct. Now all we’ve got to do is find the rest of her.”

“It is a woman’s then?”

Penterell smiled again. “How many men d’you know paint their nails?”

“The killer could have painted them afterwards.”

“It wouldn’t have flaked off if he had.”

“True. Although I don’t think it’s a coincidence the nail polish exactly matches the colour of the roses.” It would not have been a particularly difficult task. There were dozens of varieties of rose. “Why did you say ‘he’?”

“The chances of a woman doing such a thing are remote, to say the least.”

“Why? Just as many husbands are murdered by their wives as vice versa.”

“The victim was a woman.”

“Perhaps she had been seeing someone else’s husband.”

“Are you?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Sorry. That came out wrong. Are you currently seeing a married woman?”

“No. I never have – well, not once I found out they were married. Why d’you ask?”

“There must be a reason why the arm was sent to you.”

“I get rubbish from all kinds of lunatic. It’s usually just a pathetic plea for attention.”

“Rubbish?”

“You know what I mean.” Johnny reached into the inside pocket of his jacket that hung on the back of the chair. “I received this on Saturday.”

Penterell’s eyes lit up. “It must have been sent by the same person.”

“Indeed. The killer, if that is what he or she is, must be a religious nut. I’ve never heard of St Anastasia or St Basilissa. Have you?”

“No. Perhaps he’s going to work his way through the alphabet: A, B, C . . . You should have produced this straightaway. It corroborates the suggestion that you’re specifically being targeted.”

“I doubt they’ll find any decent prints apart from mine – and yours.”

In his eagerness to see the postcard, the detective had forgotten standard procedure. He flushed and dropped the evidence on to the table.

“I don’t suppose you still have the envelope?”

“No – but it was the same as the one that arrived today. What are you going to do?”

“It’s not up to me – not that I’d tell you, even if it were. Inspector Woodling is in charge of the investigation.” He carefully picked up the postcard by a corner and placed it in the folder, which appeared to contain a single piece of paper.

“Well, I’ll let you know if anything else turns up.”

“Thank you.” Penterell’s drily ironic tone was not lost on Johnny. “And I’ll let you know if you have to make an official statement. In the meantime, I wouldn’t be too worried if I were you.”

“Worried? Why should I be worried?” Johnny hadn’t been worried – but he was now.

“If someone’s trying to gain publicity, they’re not going to chop off your arms – they need you to be able to use a typewriter.”

“That’s good to know.” Johnny grabbed his jacket and made for the door. Before he could turn the knob, Penterell placed a large hand on top of his. Unlike Johnny’s, it was cool and dry.

“You won’t say anything about the postcard will you?”

“No. Why should I? I’d already mucked up any incriminating fingerprints.” Penterell looked relieved.

“Thanks. I’d hate your friend to get the wrong impression of me.”

“Friend?”

“Sergeant Turner.”

So that was why he’d initially been so ingratiating. Although they had never deliberately kept their friendship secret, Matt and Johnny hadn’t shouted it from the rooftops either. Even so, it seemed their connection was common knowledge at Snow Hill. Perhaps that’s why Matt had been so angry. He loathed being put in a compromising position.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: