По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

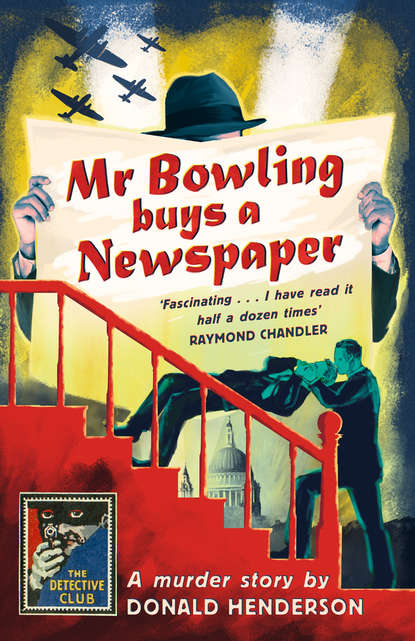

Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter XX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXII (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_d3753329-dc04-55e1-9419-f2b9a1270d53)

DONALD HENDERSON’S Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper earned considerable acclaim when it was first published in 1943, but for many years the book has been out of print. This neglect seems unaccountable, given that its admirers included Raymond Chandler. As readers of this welcome reissue will find, Henderson crafted a distinctive work of fiction; what is more, the story behind it is equally intriguing, while the tale of the author’s life is not only thought-provoking but also poignant.

Chandler wrote ‘The Simple Art of Murder’, his critical essay about the crime genre, which famously proclaims ‘down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid’, for the Atlantic Monthly. It appeared in December 1944, not long after Henderson’s book was published. Having flayed several leading writers of classic whodunits, Chandler talked at length about Dashiell Hammett’s gift for writing realistic crime fiction, before saying: ‘Without him there might not have been … an ironic study as able as Raymond Postgate’s Verdict of Twelve … or a tragi-comic idealization of the murderer as in Donald Henderson’s Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper …’

To have one’s book name-checked by such a major author, and in an essay which has been much-quoted over the years, would be a fillip to any struggling novelist’s career. Tragically, Henderson did not gain any long-term benefit from it; less than three years later he was dead, at the age of 41. In the course of his short and often troubled life, however, he published fourteen novels, as well as non-fiction books, stage plays and radio plays.

Until recently, little was known about Henderson, and even less had been written about him and his work. Thanks to the diligent and invaluable research of Paul T. Harding, much information has come to light, and Henderson’s fragmentary archive has been presented to the University of Reading. Paul Harding has also edited an unpublished memoir written by Henderson; its title The Brink comes from the final sentence, which sums up the author’s bleak worldview: ‘There is always a chasm gaping at one’s feet, and although merry enough about it, most people finally get a little tired of hovering on the brink.’

Donald Landels Henderson was born in 1905; he had a twin sister, but their mother died four days after giving birth. Henderson’s twin, Janet, also died in childbirth, when she was 28. Their father re-married when the twins were four, and Henderson was to say, ‘I cannot pretend to have enjoyed anything very much about my childhood or adolescence.’ He was educated at public school, and under pressure from his businessman father he took up a career in farming. But agricultural life didn’t suit Henderson, and a stint as a publisher’s salesman brought only misery. He enjoyed better fortune working for a stockbroker, but he abandoned the City in his mid-twenties during a turbulent period when he suffered a nervous breakdown.

Since his teens, he had enjoyed acting, and had also dreamed of becoming a writer. He joined a touring repertory company, and married an actress called Janet Morrison, a single parent who later gave up her son for adoption. The marriage soon failed, and the couple separated, although they did not divorce for some years.

Henderson began to combine writing with his acting career, but this was a period of worldwide economic depression—‘the Slump’—and money was always short. Chapter titles in The Brink such as ‘Poverty Street’, ‘Another Failure’, ‘Disaster’, and ‘The Awfulness of Everything’ give unequivocal clues to his melancholy during much of the Thirties. He had parts in plays such as Rope by Patrick Hamilton, a writer with whose dark thrillers his own work is sometimes bracketed.

After a failed theatrical venture in London, ‘I was not in a fussy mood … I got a room in Surbiton … and in a fearful burst of enthusiasm I sat down and wrote three novels running, scarcely leaving myself time to think them out, so anxious was I to get farther and farther away from the brink of the precipice. The books in question were Teddington Tragedy, His Lordship the Judge and Murderer at Large, and they were published between October 1935 and October 1936. In his memoir, Henderson supplies little detail about the influences on his crime fiction, although he acknowledges that the nineteenth-century case of the serial killer William Palmer was an inspiration for Murderer at Large.

Henderson’s account in his memoir of his time in farming gives, perhaps unintentionally, a hint about the dark side of his mind: ‘There were a lot of rats on the farm and I enjoyed many a rat hunt with the dogs. Sometimes you didn’t need dogs … We were constantly rat trapping, at which I became really expert, and I know of few greater thrills, including getting a book accepted, than hurrying along next morning to see if you have caught anything and finding that two angry, terrified little eyes are staring at you murderously. Or even more than two.’ His account of the homicidal career of Erik Farmer (was the surname a nod to his previous profession?), the loathsome protagonist of Murderer at Large, is equally chilling.

Procession to Prison, a crime novel about a ‘trunk murderer’, appeared in 1937; it was well received, but thereafter Henderson ‘could sell nothing I wrote for fully two years … The irony of the literary life, as I have experienced it, seems to lie in the fact that, when you are all but down and out, you can write well, but your luck is never any good from the selling point of view. Poverty breeds more poverty.’ Henderson tramped the streets of London and Edinburgh looking for work ‘with my press cutting book under my arm’, but without success. He had lost his nerve as an actor, and seems—although the chronology of his memoir is vague—to have spent two summers camping out in the open. After a spell in hospital, he tried to put together a book of famous trials, but failed to interest a publisher in the project.

He had better luck with a comedy thriller play called The Secret Mind, but his attempts to enlist for military service were rebuffed, and he became an ambulance driver, only to be badly injured during the blitz in September 1940. The following year, deemed unfit even for work in civil defence, he started to write a new novel—Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper.

Henderson’s explanation in The Brink of the concept he had for the book was striking: ‘It was to be a religious novel, but because publishers and everyone were always so terrified of religion, or bitter about it, unless very delicately presented, I would also make it a murder novel, to help the sales. It had a magnificent plot—though I am bad at plots—and of course I should be told I had written a “detective” story because there happened to be a detective in it. But that didn’t matter, as long as I sold it. It would be, for a change, about a man who wanted to get caught, and hanged, because he was rather browned off about life in general … I broke my rule and started this book without knowing for certain what the end would be … I decided that there must be plenty of humour in the book, to take the edge off the sombre, brooding background … I wrote the book with fearful haste and enthusiasm … in about a week and a half, straight onto the typewriter.’

The book struggled at first to find a publisher, and after another spell of acting, Henderson joined the BBC. Finally, things began to look up. He again came across Rosemary (‘Roses’) Bridgwater, who had been his girlfriend many years earlier, and once he had secured a divorce from his first wife, they married and moved into a flat in Chelsea. The novel eventually sold both in Britain and the US, and attracted positive reviews. Not everyone, however, was as impressed as Raymond Chandler. In The Brink, Henderson quoted a letter sent to his publishers by someone from Edinburgh who signed themselves as ‘Lover of Clean-Minded Literature’ which began:

‘I have read Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper and paid 8/6d for it. With the exception of Mrs Agatha Christie and also Miss Anna Buchan, I will never again buy a book without first hearing it recommended by a friend. This book is the last word in filth and should never have been printed by you …’

For Henderson, though, the popularity of the book ‘made up to me for years of despair’. He wrote a new crime novel, Goodbye to Murder, in about ten days, and adapted Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper for the stage. His wife gave birth to a son in January 1945, although a second son, born in December of the same year, died when only a few days old. The play of the book was staged in 1946, achieving critical success, and the film rights were sold. At this point, the manuscript of The Brink comes to a rather abrupt end. Henderson’s health was failing, and he died of lung cancer on 18 April 1947. Although Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper was televised live by the BBC in 1950, and again in 1957, inevitably his reputation began to fade.

Yet his writing, at its best, is distinctive enough to deserve reconsideration. The principal influences on his crime fiction are surely not Hammett, as Chandler suggested, but rather C. S. Forester, author of Payment Deferred (Henderson’s memoir mentions the homicidal protagonist, William Marble, in the context of a discussion about Charles Laughton, who played Marble in the stage and film versions of the book) and Francis Iles, author of Malice Aforethought and Before the Fact. Forester and Iles wrote with a chilly irony that also runs through Henderson’s work, and that of other occasional crime novelists of the period, such as C. E. Vulliamy, Bruce Hamilton and Raymond Postgate. ‘I would not like to say where my fascination for murder and disturbed mental conditions came from,’ Henderson said. Whatever its origins, it resulted in his producing a handful of books as unorthodox as they are powerful.

MARTIN EDWARDS

July 2017

www.martinedwardsbooks.com (http://www.martinedwardsbooks.com)

NOTE (#ulink_48948dbb-beb7-5c16-9b2b-e486d803569e)

THE characters in this book are fictitious; no portrayal of any person, living or dead, is intended.

CHAPTER I (#ulink_b722a0eb-4885-588c-b24e-fe12c87f009d)

MR BOWLING sat at the piano until it grew darker and darker, not playing, but with Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto in D Flat Minor opened before him at the first movement, rubbing his hands nervously, and staring across the shadowy room to the window, to see if it was dark enough yet. The window was wide open, and at first the evening was a kind of green, such as you would expect in a London summer, then it got grey, then it got muddy brown; then it turned black and safe. It was not that he was going to do anything very special, but he got into moods when he didn’t care to talk to people. In just the same way, he often got into desperately lonely moods; moods which might have been called suicidal, had he not been a man incapable of committing suicide, for he had too much of a sense of humour for such a cold and deliberate act. He went quietly past the little telephone cupboard, paused outside his door and listened. Then he stole past the two doors and the thin staircase which led to the top floor, taking the broader staircase down to the second, and then the first floor. He passed various doors on the ground floor and slipped out into the square and was soon in Notting Hill Gate. In his public school accent, he asked for an Evening Standard. When there wasn’t one left, he said he would take anything, he didn’t care, on this occasion, what the paper was. It wasn’t war news he was after, he had put the war out of his mind, so far as it was possible. He was bored with war and felt entitled to be. You could regard it as peace time if you liked, if you had a good imagination. He stumbled along in the blackout to the Coach and Horses, where it was cheery, and where one of the barmaids wasn’t too bad, though seeing her made him decide once again: ‘I’ll never kill a woman again! Not on your life! Things happen you don’t expect!’ All the same, he’d had to do it, it was a Heaven-sent chance. There was something about the bachelor feeling, after those dreadful years, that dreadful woman, poor thing, whatever you do, don’t marry too young. He ordered a large whisky, two shillings, but who cared, drank it neat and ordered a pint of Burton and Mild, made a few mumbling remarks and gave his quick, head-jerking expression, like a polite man not really listening, and went along to the sandwich counter. He ordered soup and some ham sandwiches and started in at his paper. He peered all over it, up and down and round about. There was nothing. It was all right. There was nothing at all. He had another look, saw a Standard discarded on a seat, pinched it and looked all through it, and set to at his sandwiches. He tossed back his beer in two gusts. There was the shadow of him on the white wall. His head going back, his thick hands holding the tankard, his blue jacket rather solid. His second murder, and he’d got away with it. Perhaps the body had been found, and perhaps it was in the morgue, but there was nothing whatever about Mr Watson in the papers, after three whole days. He ate his sandwiches and soup together, sipping at the brown soup, and then biting at a sandwich. Then he ordered some more beer, he liked beer, though it gave him a bit of a pot belly. Then he ordered a cigar. He paid one-and-six for it. Then he went out and fumbled along up the hill to the pub he liked called The Windsor Castle. He liked the public bar there, it was like a country pub, there were benches and two lots of darts going on. He sat and had a bit of a think. He got a glimpse of himself in the mirror there and thought: ‘Well, I dunno, I think I look rather decent.’

Across the bar, a girl sat with a soldier and said about Mr Bowling: ‘There’s that man who often comes in here. Doesn’t he look awful? There’s something about him.’

But over in Ebury Street, Victoria, the crowd thought he was marvellous. Queenie often said: ‘Oh Lor’, I’m fed up, let’s ring up poor old Bill! He’ll cheer us up, and at least he’s a gentleman!’ She’d get busy dialling Park 4796. She did it now and the others sat around with the Watney bottles. ‘Hallo? Oh, could I speak to Mr Bowling, please? Is it a trouble?’ Only, sometimes one of the other tenants answered the telephone, instead of the maid, thinking it was for them most likely, and they got snooty when it wasn’t for them. ‘He’s out,’ they’d say without going to knock.

‘I wonder if you could be so kind as to give him a message when he comes in? It’s Queenie Martin, he’ll know. We’d love him to come over?’

… Stumbling back from The Windsor Castle, Mr Bowling went in to Number Forty and hurried up to his room. He was just beginning to feel pretty good. Regular practice during the blitz had given him a pretty good head, and all that subsequently boring time in the Ambulance Service, until he got himself invalided out with his queer heart, so it needed a good deal now to feel really good. He told himself he felt perky. He was just beginning to get the feeling of being a bachelor again, and living alone in a room in the old way which he so used to hate. A man married for reasons of loneliness, and so as to make love regularly, in his view, more often than for any other reason. Sometimes, if he was lucky, for money. If he was really lucky, he married for love. But there, some people had the luck, others didn’t. He put on the light and sat on the divan thinking: ‘I expect I look rather nice, sitting here, rather a quiet sort of chap, sad.’ He smiled in the way he would have smiled had someone been watching who was prepared to say: ‘Poor old Bill! There, there! There, there!’ He started to have a little cry. He cried into his thick hands. There were so many reasons for those tears, they started so very long ago. He thought: ‘I’m not a sinner at all, really. No worse than the next chap. I’d help anyone. I jolly soon started in at war work. It was partly the change, we all like change, and I got fed up with insurance. I never thought of this new line, not then. Not until we got a direct hit and we got buried, and she started up that awful screaming. And I put my hand on her mouth, close to her nose. My, she went out quickly, like a snuffed candle. It was only murder if you analysed it. There were worse things. Blackmail was worse. Homosexuality was worse. Who said murder was the only capital crime? It wasn’t so in the old days. You got stoned to death for all sorts of things. Poor old girl, but she was a cow, a real cow, what a cow she was. Poor old dear. And if it hadn’t been me, it might have been the roof falling in. Who could tell? Anyway, it’s between me and my God.’ And he thought: ‘And for the first time, I got a bit of money out of something! Insurance! I’d never even thought of that!’

The maid had done the pink curtains and the blackout. He was moving to the piano when he saw the note under the door. Queenie. May as well go over, she might have some gin. He got his bowler hat again and lost no time in going out and across to the District Railway. He found Queenie and the crowd full of larks, all the Services represented, military and civil defence, and hardly room to breathe. ‘Struth,’ he said in his public school accent. ‘No air at all! I shall pass out!’

‘You pass out,’ Queenie said. ‘Here, dear, have some gin. I saved it.’ Queenie’s husband was tight and lay on the bed. He was a very boring man who had a job in the M.O.I. They all looked like him up there.

There were a pair of twins, kids in the A.T.S.

Mr Bowling thought:

‘I wonder what this crowd would think if they knew.’

And he thought:

‘Perhaps they will know soon. I’m doing my level best.’

But perhaps this train of thought was the gin.

CHAPTER II (#ulink_9df2afd8-bf01-5405-816f-189ef2b2c1ae)

BEFORE he killed his wife, which in a sense had not been premeditated, not really, Mr Bowling had reached such an intense pitch of despair about life, that he had thought of doing a murder and more or less making it reasonably easy for the police to catch him and arrest him. It was quite an honest thought, and it recurred now and then when he had had a drop of gin. After all he had been through since leaving school, all the bitter disappointments, and above all the drabness and the poverty, and his awful marriage, he had frequently and honestly felt that to get into the public eye in this way would be better than dying at last utterly unknown and exhausted spiritually. His music had failed to get him into the public eye, and goodness only knew how hard he had worked for many years, why not make a sensation of this sort? Repression, no doubt. And sex starvation. Soul starvation. Ordinary starvation, too. To hang, would at least end it and be better than suicide. And to win the appeal and get twenty years, even that would be better. Twenty years rent free and all found wasn’t so bad, ask anyone who knew about these things, these years between wars? Ask them! What a joy this new war was, after the disappointment of Munich! ‘It’s Peace,’ the placards all said. Hell, the same old humdrum, on we go as before! And then September the third. And then at last the bombs. Frightening, yes, but thrilling. Change. Who looked forward to the next peace, and the cold, starving agony nobody knew how to prevent?

He started up a coughing fit.

He swore. Somebody tapped angrily on a wall. ‘Bitch,’ he said. A man couldn’t even cough in his own home.

Suddenly it dawned on him that this wasn’t much of a home. The one thing which had made him stick his marriage was the bit of a home, it was the carpet, a nice red one. And then a direct hit, and the whole lot gone, how glad he was. Coughing, then, in the dust and mess, he’d thought, well, thank God, now a wealth of ugly memories are gone forever, photographs, books, ornaments, yes, even the bloody carpet, you can have the lot! They stood imprisoned together in a kind of black pit and she’d started up that screaming right in his ear, and he’d put out his hand. ‘Are you hurt?’

‘No …!’

‘Well, shut up screaming, we’re not trapped, there’s a light, it’s the street!’ It was the Fulham street. ‘See?’

But she screamed like a maniac.

It was easy to stop it.