По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

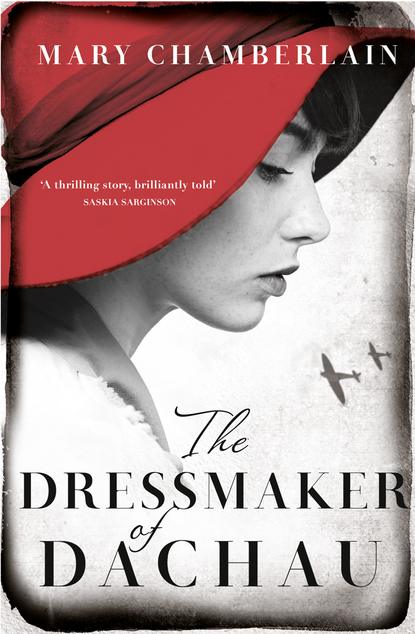

The Dressmaker of Dachau

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The officer lifted his chin, studied their faces. She dared not look at Stanislaus. Her armpits were wet. She began to sweat behind her knees and in the palms of her hands.

The guard said nothing, waved them through with a flick of the wrist, summoned the next in line, a large family with five children.

Walked through, just like that. The strain had made her dizzy, but she was almost disappointed too. No one had given her the chance to say the words she’d practised over and over in her head. Stanislaus wouldn’t know how clever she could be.

‘We made it,’ he said.

They were in Belgium.

The relief brought with it exhaustion. Her legs ached, her back hurt, another blister had formed on her heel. She wanted this to be over. She wanted to go home, to open the door, Hello, Mum, it’s me. She wasn’t sure she had the strength to walk another yard, and she had no idea where they were.

‘Are we far from the sea?’ she said.

‘Sea?’ He laughed. ‘We’re a long way from the sea.’

‘Where do we go?’

‘Namur.’

‘Why?’

‘No more,’ he said, winking. ‘Get it?’

‘Where is it? Is it on the way?’

The family that had been behind them in the queue jostled forward, scratching her legs with the buckle of a suitcase, pushing her closer to Stanislaus. She leant towards him.

‘I want to go home,’ she said. ‘To England. Can’t we go back now?’

‘Maybe.’ His voice was distant. ‘Maybe. But first Namur.’

‘Why? I want to go home.’ She wanted to say, this minute. Stamp her feet, like a child.

‘No,’ he said. ‘Namur.’

‘Why Namur?’

‘Business, Ada,’ he said. She couldn’t imagine what business could be taking them there.

‘Promise me.’ There was panic in her voice. ‘After. We go home.’

He lifted her hand, kissed her knuckles. ‘I promise.’

They hitched a lift to Mons and caught a crowded train to Namur that stopped at every station and red light. It was evening by the time they arrived. The baguette was all Ada had eaten since they’d left Paris eighteen hours ago and she felt faint and weak. Stanislaus took her by the elbow, guided her away from the station, down the side streets. She had no idea where they were going, or whether Stanislaus knew the way but they stopped by a small café above which was a painted sign, ‘Pension’.

‘Wait here,’ he said. ‘I’ll organize it.’

She sat at a table and chair outside. This side of the street was in the shade but she was too tired to walk to the other side, where the last of the May sun was shining. Stanislaus came out.

‘Everything,’ he said, ‘is organized. Madame will give us a simple meal, and while we’re eating her daughter will arrange the room.’ As he spoke, Madame appeared with two glasses of beer which she placed in front of them.

Stanislaus picked up his glass. ‘To you, Ada Vaughan. Namur.’

She touched her handbag with the teddy bear, and held the glass so it chinked with his and smiled at him. Lucky.

Paté and bread, sausage. The beer was cloudy and sweet, and she drank two long glasses. It made her light-headed, and she was glad for it. She hadn’t been tipsy since before the war. The early days with Stanislaus seemed like another age now, at the Café Royal, a Martini or two, with a cherry on a stick. Content and flushed with love, they’d sashayed down Piccadilly to the number 12, where he’d kiss her under the lamp-post, tender lips to hers. She’d suck peppermints on the way home so her breath didn’t smell. It was like that just now. Stanislaus’s mood had evaporated, his worries – their worries – over. Namur. No more. No more temper or brooding silences. He was in good heart again, but he swung so quickly from light to dark. It worried her. His moods made her change too. When he was sunny so was she, nimble toes and bubbling breath. But when his mood turned cold it choked her like a fog.

They went upstairs after dinner. She was unsteady on her feet, could smell herself tart and musty from the day, her hair sticky with dust and sweat. Madame had left a jug of water and a wash bowl on the table and had laid out a towel and a flannel.

‘I must,’ her words slurred, ‘wash.’

Stanislaus nodded and walked to the window, looked out over the street with his back to her. Ada wet the flannel and rubbed. She heard her mother in her head, saw herself as a child standing by the sink in the kitchen at home. Up as far as you can go, down as far as you can go. She giggled into the cloth, and found herself crying, a lunge of homesickness and fear, as if she was tumbling deep into a canyon and couldn’t stop herself.

She was aware of Stanislaus catching her as she fell, laying her on the bed and fumbling with the buttons on his flies. Her head was spinning, her eyes heavy. She just wanted to sleep. She felt him open her legs, enter her with an impatient thrust, sharp rips of pain that made her cry out. He lifted himself off her and lay by her side. Her legs were wet. He’d kept his shirt on, she could see, even through the blur of beer.

It was dark when she woke. Then she heard it. The distant blast of an explosion, the boom of heavy guns. The curtains had been left open and through the window the night sky streaked white and vermilion.

‘Stanislaus.’ She groped for him next to her. The bed was empty, the sheets cold and smooth. She sat up, awake, panic gripping her body, short of breath.

‘Stanislaus.’ His name echoed round the empty room. Something was wrong, she knew. She fumbled for her clothes, pulled them on, please God let him come back. There were steps outside. It must be him. Just went out for a cigarette. She opened the door but it was Madame who was walking up the stairs, her way lit by a small oil lamp.

‘Mademoiselle,’ she was panting from the climb. ‘The Germans are here. You must come, to the basement.’

‘My husband,’ Ada said. ‘Where is my husband?’

‘Follow me,’ Madame said, lighting the way for them both. She held up the long skirt of her nightdress with her free hand.

‘But my husband.’ Dread clamoured, a shrill, persistent klaxon. ‘My husband. He’s not here.’

They had entered the café now. The room was dark. Ada could make out the tables and chairs, the glisten of bottles behind the bar. Madame opened a trap door and began to lower herself down.

‘Come,’ she said.

Ada looked for Stanislaus in the gloom, listened for his breathing, smelled the air for his scent, but her nostrils filled with the tang of stale beer and burnt sugar.

‘Mademoiselle. Now. You must come now. We are in danger.’ A hand tugged at her ankle. Stanislaus wasn’t in the room. He was out there, in the night, by himself, in danger. A boom thundered in the distance. The hand tugged again at her foot so Ada lost her balance and had to steady herself on a chair.

‘I’m coming,’ she said.

She looked for the glow of his cigarette in the cellar, his shadow in the vaults. You took your time, Ada. Madame closed the trap door, and switched on a single bulb which shed a dim light through the darkness. The cellar was full of barrels stacked five high, and a pair of porters’ trolleys. The earth floor smelled of mushrooms. Madame had brought down a sheet of linoleum and two hard-backed chairs. There was a hamper next to one, with bread and cheese. She had prepared for this day, knew that war was coming. Ada should have known too.

‘My husband,’ Ada began to whimper. ‘He’s not here.’

‘Your husband?’

‘Yes. Where is he?’

‘Your husband?’