По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

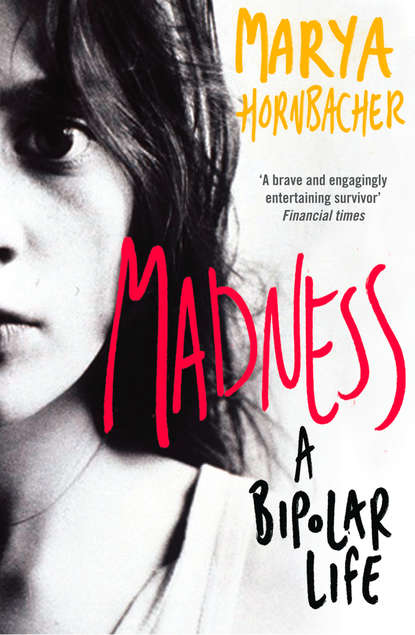

Madness: A Bipolar Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

My feet are flying. I hate it when my feet are flying. I sit up and grab them with both hands. It’s dark, and I stare at the little line of light that sneaks in under the door.

The light begins to move. It begins to pulse and blur. I try to make it stop. I scowl and stare at it. My heart beats faster. I am frozen in my bed, gripping my feet. The light has crawled across the floor. It’s headed for the bed. I want it to hold still, so I press my brain against it, expecting it to stop, but it doesn’t. The line crosses the purple carpet. I want to scream. I open my mouth and hear myself say something, but I don’t know what it is or who said it. The little man in my mind said it, I decide, suddenly aware that there is a little man in my mind.

The line is crawling up the side of the bed. I tell it to go away. Holding my feet, I scootch back toward the wall. My brain is feeling the pressure. I let go of my feet and cover my ears, pressing in to calm my mind. The line crests the edge of the bed and starts across the flowered quilt. I throw myself off the bed. I watch the line turn toward me, slide off the bed, follow me into the corner of my room.

I want to go under the bed but I know it will follow me. I jump up on the bed, jump down, run into the closet and out again, the humming in my head is excruciatingly loud. The light is going to hurt me. I can’t escape it. It catches up with me, wraps around me, grips my body. I am paralyzed, I can’t scream. So I close my eyes and feel it come up my spine and creep into my brain. I watch it explode like the sun.

I drift off into my head. I have visions of the goatman, with his horrible hooves. He comes to kill me every night. They say it is a nightmare. But he is real. When he comes, I feel his fur.

I don’t come out of my room for days. I tell them I’m sick, and pull the blinds against the light. Even the glow of the moon is too piercing. The world outside presses in at the walls, trying to reach me, trying to eat me alive. I must stay here in bed, in the hollow of my sheets, trying to block the racing, maniac thoughts.

I turn over and burrow into the bed headfirst.

I HAVE THESE crazy spells sometimes. Often. More and more. But I never tell. I laugh and pretend I am a real girl, not a fake one, a figment of my own imagination, a mistake. I never let on, or they will know that I am crazy for sure, and they will send me away.

This being the 1970s, the idea of a child with bipolar is unheard of, and it’s still controversial today. No psychiatrist would have diagnosed it then—they didn’t know it was possible. And so children with bipolar were seen as wild, troubled, out of control—but not in the grips of a serious illness.

My father is having one of his rages. He screams and sobs, lurching after me, trying to grab me and pick me up, keep me from going away with my mother, but I make myself small and hide behind her legs. We are trying to leave for my grandmother’s house. We are taking a train. I have a small plaid suitcase. I come around and stand suspended between my parents, looking back and forth at each one. My mother is calm and mean. The calmer she gets, the more I know she is angry and hates him. She hisses, Jay, for Christ’s sake, stop it. Stop it. You’re crazy, stop screaming, calm down, we’re leaving, you can’t stop us. My father is out of control, yelling, coming at my mother, grabbing at her clothes as she tries to move away from him. Don’t leave me, he cries out as if he’s being tortured, choking on his words, don’t leave me, I can’t live without you, you are the reason I even bother to stay alive, without you I’m nothing. His face is twisted and red and wet from tears. He throws himself on the floor and curls up and cries and screams. I go over to him and pat him on the head. He grabs me and clutches me in his arms and I get scared and try to push away from him but I’m not strong enough. I finally get free and he stands up again, and I stand between them, my head at hip level, trying to push them apart. He kneels and grabs my arms, Baby, I love you, do you love me? Say you love me—and I pat his wet cheeks and say I love him, wanting to get away from him and his rages and black sadness and his lying-on-the-couch-crying days when I get home from preschool, and his sucking need, and I close my eyes and scream at the top of my lungs and tell them both to stop it.

My father calms down and takes us to the train station, but halfway there he starts up again and we nearly crash the car. We leave him standing on the platform, sobbing.

“Why does he get like that?” I ask my mother. I sit in the window seat swinging my legs, watching the trees go by, listening to the clatter of the wheels. I look at my mother. She stares straight ahead.

“I don’t know,” she says. I picture my father back at home, walking through the empty house to the couch, lying down on his side, staring out the window like he does some afternoons, even though I tell him over and over I love him. Over and over, I tell him I love him and that everything will be okay. He never believes me. I can never make him well.

CRAZY IS NOTHING out of the ordinary in my family. It’s what we are, part of the family identity, sort of a running joke—the crazy things somebody did, the great-grandfather who took off with the circus from time to time, the uncle who painted the horse, Uncle Frank in general, my father, me. In the 1970s, psychiatry knows very little about bipolar disorder. It wasn’t even called that until the 1980s, and the term didn’t catch on for another several years. Most people with bipolar were misdiagnosed with schizophrenia in the 1970s (in the 1990s, most bipolar people were misdiagnosed with unipolar depression). We didn’t talk about “mental illness.” The adults knew Uncle Joe had manic depression, but they didn’t mind or worry about it—just one more funny thing about us all, a little bit of crazy, fodder for a good story.

This is my favorite one: Uncle Joe used to spend a fair amount of time in the loony bin. My family wasn’t bothered by his regular trips to and from “the facility”—they’d shrug and say, There goes Joe, and they’d put him in the car and take him in. One day Uncle Frank (who everybody knows is crazy—my cousins and I hide from him under the bed at Christmas) was driving Uncle Joe to the crazy place. When they got there, Joe asked Frank to drop him off at the door while Frank went and parked the car. Frank didn’t think much of it, and dropped him off.

Joe went inside, smiled at the nurse, and said, “Hi. I’m Frank Hornbacher. I’m here to drop off Joe. He likes to park the car, so I let him do that. He’ll be right in.” The nurse nodded knowingly. The real Frank walked in. The nurse took his arm and guided him away, murmuring the way nurses always do, while Frank hollered in protest, insisting that he was Frank, not Joe. Joe, quite pleased with himself, gave Frank a wave and left.

Depression (#ulink_63fe64a2-4700-5433-8b3d-e6aec71f65c1)

1981

Maybe it begins when I am seven. I’m in bed. It’s too sunny outside, I can’t go out. The blinds are drawn and yet they let in a little light, and the little light pierces my eyes. I turn my face into my pillow. It’s cool and safe in my sheets. My father comes in.

Time to get up, kiddo.

(Silence.)

Kiddo.

(I pull the pillow over my head to block the incessant light.)

Kiddo, are you getting up?

No.

Why not?

I’m skipping today.

What’s the matter with today?

I sigh. I despair of ever getting up again. I cannot move. I will not move. Everything is horrible. I want to go to sleep forever.

I can’t go to school, I say.

Why not?

I bang my head on the mattress and let out a shriek. I sigh and flop onto my back and shade my eyes.

There’s an art project. I burst into tears.

Oh, my father says, unsurprised. Is it complicated?

It’s very complicated, I wail. I can’t do it. I don’t want to do it. So I’m sick. I wipe my nose and let the tears fall into my ears.

Okay, my father says.

I’m staying home.

Okay.

Okay. Okay. Now I will be okay. No crowded classroom, no scissors, no paste, no other kids, no cafeteria lunch, no recess, no wide sky and too much sun.

The world outside swells and presses in at the walls, trying to reach me, trying to eat me alive. I must stay here in the pocket of my sheets, with my blanket and my book. I will not face the world, with its lights and noise, its confusion, the way I lose myself in its crowds. The way I disappear. I am the invisible girl. I am make-believe. I am not really there.

I don’t come out of my room for days. Days bleed into weeks. I lie in bed in the dark.

Prayer (#ulink_726b66d8-fde6-58a8-9794-838140c41e9c)

1983

On my knees. Praying. Pleading. The basement floor is cold beneath my knees. I come here to hide, to hide my prayers. My mother would mock me. God is merely a weakness for people who need to believe. She wouldn’t understand that I am chosen to speak for all the sorrows of the world.

I’m not crazy. God has called me and I have no choice but to answer, or I will be sent to hell. It all depends on me. And so I pray myself to sleep, and pray the second I wake, and pray all day, terrified that God will catch me slacking off and punish me severely.

My knees grow sore and my heart beats a million miles an hour. I panic. I practically pant. My mind spins with the things I am forgetting to pray for, things I have done, there is a light flashing in my brain, like the headlight of a train in the dark, the dark is my mind, which teems with sins, which torment me with their noise. I can hear the sins whisper; are they inside my head or outside my ears? Are they in the basement? Coming from the water heater, the washing machine? God answers at last. You may get up, I hear him say. His voice reverberates against the concrete walls.

Halfway up the stairs, I hear God call me to prayer again. I kneel and pray. He calls me in the kitchen. Calls me in my bedroom. Calls me at school. I raise my hand, hurry into the restroom, kneel on the floor of the stall, the restroom empty and echoing with my rapid breath, echoing with the shrieking, pounding in my head. I pray in class. I pray in the car, after dinner, all night long—hours after silence has settled around the house, my mouth moves with manic prayers.

God watches me, sees my every mistake, every sin. God’s voice booms in my head, now praising me, his chosen one, now spitting at me, sending the snake into my mind. It curls itself around itself, its body pressed against the walls of my skull. I lie in bed, rocking, my head in my hands, the snake flicking its tongue at the backs of my eyeballs. It sinks its teeth into the gray, wet brain. I press my open mouth to the mattress and scream.

Food (#ulink_9a00113d-5040-58ec-8c0e-b88c7b60aec9)

1984