По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

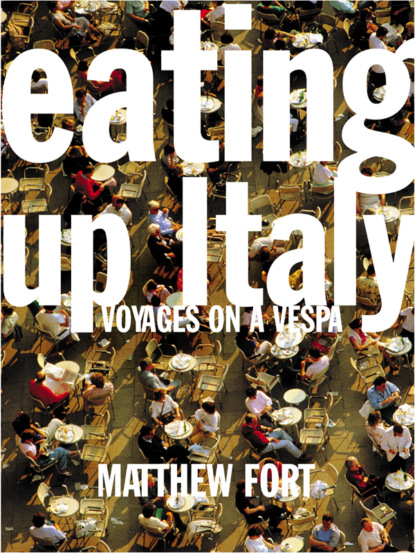

Eating Up Italy: Voyages on a Vespa

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Put the risen dough on the work surface, pull open in the middle and punch down. Add the softened pork fat. Knead until the dough is elastic and silky. Put back in the bowl and leave in a warm place to rise again.

Roll out half the dough to cover the bottom of a round ovenproof tin greased with lard. Cover with the pork rind, sliced hard-boiled eggs, sausage and pecorino. Cover with the rest of the dough and seal with half the beaten egg. Prick the surface with a fork and brush with the remaining beaten egg.

Bake at 180°C/Gas 4 for 30 minutes until golden brown.

3

GETTING STUFFED

PIANAPOLI – CASTROVILLARI – DIAMANTE – SCALEA – MARATEA – SAPRI – SALA CONSILINA – NAPLES

Carne

Ah, but to taste, that was another matter. The chicken was redolent of the farmyard, the lamb robust with free-ranging and the pork subtle and unctuous as an undertaker.

3

GETTING STUFFED

PIANAPOLI – CASTROVILLARI – DIAMANTE – SCALEA – MARATEA – SAPRI – SALA CONSILINA – NAPLES

Federico guided me to the right road for Cosenza from Pianapoli and sped me on my way. Up and up Ginger and I climbed, heading north-east from Feroleto Antico, and passing by way of the straggling villages of Serrastretta, Soveria Mannelli and Rogliano towards the centre of the country. At some point I should have been able to see both the Ionian and Tyrrhenian Seas, but the cloud was low and thunderous, and I wasn’t of a mind to hang around for another drenching.

The Sila Piccola, which I had now entered, wasn’t as wild as the Aspromonte. The curves were gentler, the slopes not quite so fortress-like. The trees were much smaller, too, and only just coming into leaf. This area had been subjected to savage deforestation for several centuries, supplying wood for the shipping industries of many countries, including Britain. Now it was gradually returning in part to its former bosky glory under a process of planting begun under Mussolini, a little-sung legacy of Fascism. There were different wild flowers, too, yellow and red orchids, broom and gorse in flower, wild irises of a velvety, royal blue, rock rose, jonquils and campions. Jays and chaffinches looped along parallel to the road.

Then I felt as if I had suddenly come over the lip of a bowl and I swept down into new country of rolling, almost Alpine pastures, small squares of corn like mats and neat, gemütlich houses. I made good speed, and came within spitting distance of Cosenza, one of the provincial capitals of Calabria on the confluence of the Crati and Busento Rivers, by midday or so. Legend has it that Alaric the Visigoth was buried in the bed of the Busento, along with his treasure, but I hurried on, putting aside the urge for lunch in favour of the urge to make progress.

I surged on towards Castrovillari, up through the Albanian part of Calabria – old Albanian, not new, the Calabria of Spezzano Albanese and Santa Sofia d’Epiro. Albanians had been in these rolling hills since they fled Turkish persecution in the fifteenth century. In spite of five centuries of acclimatisation, they have kept their own customs, language and cooking. Albanians were now returning to Italy again, less welcomed than in previous centuries. European history has a habit of repeating itself.

I settled myself at a table at La Locanda de Alia in Castrovillari, and bit into a piece of bread. It was unusually good bread, rather chewy and full of bouncy, wheaty flavours.

While Italians don’t subscribe to the division between haute cuisine and bourgeois or domestic cooking with the same enthusiasm as the French, they have developed a sophisticated range of places of public rest and recreation – locanda, ristorante, trattoria, tavola calda, pizzeria, bar, caffè – each with its own quite precise set of functions. A locanda is the equivalent to the English inn, by tradition anyway, a restaurant with rooms. It is not as formal as a hotel, nor as cosy as a guesthouse, but the Alia version was rather civilised, not to say cultured.

A couple wandered in with a very small child, all dressed in holiday gear that was as garish as it was scanty. The child proceeded to make the most tremendous din, howling as if he had been kicked. No one seemed to mind, or to take any notice, other than to raise his or her voice to be heard above the hullabaloo. Such social tolerance is as normal in restaurants of all classes in Italy as it is abnormal in Britain. It reflects the social democracy of public eating in Italy. Everyone feels quite at home in a restaurant in a way that we do not.

Then something odd happened. Hello, I thought, what’s this? Carefully, and not wishing to attract too much attention, I eased what appeared to be a foreign body out into my hand. My eyes lit on half a tooth. The bloody baker had left a tooth in the bread, I thought. Disgusting. Then a second thought struck me. Gingerly I ran my tongue around my molars. I hadn’t detected anything amiss. But, oh my God, there at the back on the right it was as if a great section of the cliffs at Dover had fallen into the sea.

Before I had time to digest this shattering piece of news, the antipasto arrived: schiuma di zucchini con salsa di formaggi freschi. Silently I thanked the kitchen for the gentle and dentally unchallenging mousse of zucchini with a sauce made of molten ricotta.

The second course, panzerotti in salsa di semi di anice silano, was altogether more potent. Aniseed is native to the Levant, and was used quite extensively by both the Greeks and the Romans. On the other hand, it was also used to flavour cakes and sweets in north Africa and northern Spain, both regions intimately involved with southern Italy, so who is to know how it really came to take its place in the Calabrian kitchen?

I was relieved that the process of chewing and swallowing did not seem to have been unduly affected. Here I was, a thousand miles or so from my dentist’s surgery, in the middle of a trip which depended on the efficient functioning of my digestive processes, which begin with the teeth.

Carne ’ncatarata in salsa di miele e peperoncino followed, an idiosyncratic combination of honey and chilli with pork, which was, according to the maître d’, Albanian in origin. Hmm. I wasn’t convinced that chilli figured prominently in Albanian cooking, so perhaps this was a Balkan dish with an Italian accent. Heat and sweetness make for ruminative eating, but I decided that it was really rather wonderful, not least because the pork was so tender that I could have sliced it up with a sheet of paper. It was a thoroughly modern dish in appearance, albeit one firmly locked into local ingredients and traditions.

Such blurring of cultural boundaries was unusual. Calabrian cooking had been defined by an awareness of absolute locality that made a coherent understanding of its essence difficult. It wasn’t a pot-pourri, or a melting pot, because there was such a clear sense of identity tied up with each dish, product or ingredient. This fierce campanilismo was the result of the isolated nature of many communities, isolated by geography, politics and history. The homogeneity that rides on the back of integrated transport systems and the priorities of commerce that has affected so much of the rest of Europe has yet to make such headway in southern Italy.

I finished with the ficchi secchi con salsa di cioccolato bianco – dried figs with white chocolate sauce. It was difficult to know what to conclude from this weird confection. Decorated with a liberal dose of hundreds and thousands like tiny beads, it was as vulgar as some of the more lachrymose baroque Madonnas in roadside niches. To taste it was tooth-achingly succulent. All in all, the dish was a modern travesty of the classic ficchi al cioccolato, which unites the influences of Eastern spices, the Moors with their love of almonds and the Spanish, who financed the package tours to the Americas that led, in the final analysis, to Cadbury’s Dairy Milk.

Of course, Britain can legitimately claim to be the world leader in puddings. No other country can match the wealth and variety of our pudding tradition, from fools to roly-polies, tarts to trifles, syllabubs to creams and custards. By comparison, the Italians are limited in their pudding horizons. True, zabaglione, the velvety combination of beaten eggs, sugar and Marsala, is a great pudding; panna cotta, happily adopted by contemporary British restaurants, passes muster in its finest form; and ice creams reach a degree of perfection in Italy that we can only dream of. But for the rest? That ludicrous confection, tiramisu? The trifle of an impoverished imagination. Crostade? Tarts as heavy as manhole covers. Panettone? Better turned into bread-and-butter pudding.

It was time to hit the road again. I knew it was time because it had just started to rain for a change.

‘Peperoncino – chilli – is most important to the cooking around Cosenza,’ Silvia Cappello had told me in Reggio di Calabria. ‘I know you find it everywhere now, but really, Cosenza is the capital of chilli. We in Reggio’ – her voice indicated that there was an unbridgeable gulf between Reggio and Cosenza – ‘are more influenced by Sicilian cooking, and the Sicilians don’t use chilli so much.’

Enzo Monaco did not agree entirely with Silvia’s authoritative statement. Enzo was the Presidente dell’ Accademia del Peperoncino. He was a plausible, agreeable fellow, with thinning hair that crept like ground cover over the curve of his head, a long nose and, behind his glasses, sloping eyes that gave him a mournful look. He was a journalist and a fluent publicist for his cause. So fluent, indeed, that he had turned it into a minor industry, employing three or four people, organising festivals, colloquia, demonstrations, promotions and a newspaper from an office housed in a stump of low-rise flats in the dishevelled seaside town of Diamante.

Peperoncino, he said, fresh, dried, flaked or powdered, was the one essential of Calabrian cooking. It cropped up everywhere, in sauces, sausages and soups, in antipasti, primi piatti and secondi piatti. It lent light and shade to fish, meat and vegetables, to pastries, pasta and even puddings. Indeed, he assured me that there was peperoncino ice cream and peperoncino cake, and proudly showed me some peperoncino biscuits that were about to come on the market thanks to his efforts.

The chilli, or capsicum, arrived in Europe from Mexico in 1492, along with potatoes, tomatoes, chocolate, tobacco, corn, turkey and sundry other delights. What on earth did the world eat before the treasure store of the Americas was opened up? The capsicum made its way to India and South East Asia by 1525, by way of Spanish and Portuguese merchant ships. The Italians gave chilli (the name is a corruption of the Central American nahuatl) a warm welcome in 1526, a passion for its qualities taking particular root in southern Italy, which at that time was yoked to the Americas by the compass of the Spanish Empire.

According to Signor Monaco, the spice was taken up by the poor to start with, to put a spring into the step of their otherwise boring and monotonous fare of pulses and vegetables. Before peperoncino there had been other spices, principally vine pepper, but vine pepper had its limitations, notably price – it had been far too expensive for any but the better-off to afford.

Peperoncini, on the other hand, were easy to grow in the Calabrian climate, with plenty of sun and plenty of water. Not only did peperoncino make the local diet look lively; it also added a store cupboard of vitamins and minerals to the mix. In Enzo’s masterwork, Sua Maestà Il Peperoncino (which translated, I think, means His Majesty the Peperoncino), he claims it’s great for acne, dull hair, cellulite, heart problems, massage. Oh, and sex, naturally. No wonder peperoncino was known as ‘la droga dei poveri’, the poor man’s drug.

But what, exactly, I longed to know, was this peperoncino or that? Was it habanero or jalapenõ or Scotch bonnet, or one of the 2,000 other members of the pepper family? Was it better fresh or dried? Were certain dishes made with one or the other? Did you find one variety being used in one place and another elsewhere? And why did it come to have such a hold over the Calabrese kitchen (not to mention the kitchens of Basilicata, Campania and the Abruzzo)?

Signor Monaco was charming, he was voluble, he was a mine of arcane information about the history, the uses and the benefits of chillies, but when it came to identifying specific varieties and their uses, ‘È peperoncino’ was about the best I could get.

Close study of his hagiography of the chilli proved slightly more revealing. He identified six significant sorts of Capsicum annuum: abbreviatum, which is small – not exceeding 5 centimetres, and conical; acuminatum, fasciculaatum, cerasferum, bicolor and the distinctly non-Linnaeic ‘Christmas Candle’. The smallest, hottest chillies are known as diavolilli, and are a speciality of the Abruzzo. Then there is a long fat chilli, known as the sigaretta; a small, pointed chilli that is dried and ground to make pepe d’India or pepe di Caienna; and capsico, a round chilli shaped like a cherry. On the subject of which chilli is used for which dish, it is impossible to provide a definitive answer because I rarely got the same answer from two different cooks.

I had other problems on my mind, too. Over lunch I told Enzo about my failure to find La Golosa, a pasta manufacturer where, I had been told, certain types of pasta were still made by hand. He smiled.

‘La Golosa. No problem. I am working with them to develop some pasta with peperoncino in it. We’ll go there now.’

It wasn’t entirely surprising that I hadn’t been able to find the factory. It was heavily disguised as a block of flats in Scalea, a Calabrian coastal Longridge or Basildon. In fact, it took up the whole of the substantial ground floor, deliveries being made on one side and the finished product being shipped out on the other. But there was no sign, name or indication of any kind that there was anything going on. As the lively and forceful Signora Golosa explained, what with the bureaucracy of a complexity and insanity that Kafka would have had trouble describing, complete with multiple sets of tax authorities, hygiene inspectors, planning offices, etc., they were not too keen on drawing attention to themselves. Hence, no signs outside.

Golosa was the family name, and the business involved husband, wife, son and the son’s girlfriend, who shared the marketing, product development and administrative duties between them. There were four ladies doing the hands-on work, all properly dressed in white coats and regulation hats. Like many small-scale Italian producers, they managed to maintain a careful balance between preserving the essence of artisanal production while also making use of the most up-to-date technology. The production area comprised a couple of large, high-ceilinged rooms with white walls and marble-tiled flooring. It was well lit, with windows back and front, and cool, and so suitable for handling pasta. Odd bits of machinery – mixing machines for working the dough, rollers, cutters, vacuum-packing machines, drying frames – were scattered around the wide open spaces.

Not all the production was strictly artisanal, but the ladies were rolling a local pasta called fusilli (with the accent on the first ‘i’) round a short, metal spike called a ferro, or firriettu in dialect, literally by hand. These fusilli were not at all like the compressed corkscrews I was used to in England. More confusingly still, I had already come across them as maccheroni and fileja. Not that it was like what we think of maccheroni, either. And piling mystery on confusion, different parts of Calabria cut their fusilli, fileji or maccheroni to different lengths. Just to complicate the issue further, according to Signora Golosa, the metal spike was sometimes squared off, and the pasta called something else, and, that, naturally, needed an entirely different sauce. Sometimes I suspect Italians of inventing subtle variations in pasta, and insisting that each is better suited to this sauce or that, in much the same way that theologians squabble over minute differences in the interpretation of some text or other. Take that class of stuffed pasta known generally as ravioli, or agnolotti to the Piedmontese, which becomes tordelli to a Tuscan or culingiones to a Sardinian or tortelli to an Emiliani. That is before we get to tortellini and tortelloni and other sub-classes. Each is favoured by a particular part of Italy, stuffed and sauced differently, and each claimed as superior by the natives of whatever particular region it comes from.

These fusilli were made by taking strips of pasta made of just grano di semola (ground durum wheat) and water about as long as a school ruler and as wide as a thumb, and with a light rolling motion of the hands, wrapping them round a long metal spike about the circumference of a knitting needle. The slightly irregular length of fusilli was then stripped off the spike and flipped on to a pile of those already finished.

There is always something of the thrill and bafflement of watching a magician in witnessing skilled people going about their business with effortless dexterity. The ladies took about five seconds to make each fusillo with easy nonchalance, hands moving with mesmerising assurance. Then came the hi-tech bit. The fusilli were spread out on fine-mesh drying racks with wooden frames, stacked on top of one another and then stacked on a trolley so that they could be popped into a special, state-of-the-art, computer-controlled drying chamber. Most were turned into pastasciutta, dry pasta of the kind you find in cellophane packets, and packed for sale. Some were kept undried for sale in Signora Golosa’s shop in Scalea. She explained that many women still make fusilli or maccheroni at home for special occasions, but that this was the only hands-on production line, as it were, doing the artisanal business.

For once the sun shone, the birds sang and God was in his heaven. On such days voyaging by scooter was full of joy. The road unravelled pleasantly beneath Ginger’s wheels. I could feel the warmth of the sun on my arms and back, and smelled the sweet freshness of spring leaf and flower. I revelled in the sense of freedom, and as I fancied taking this byway or that, why then, I did so, without the slightest concern. B roads, C roads and even, on occasion, tracks lured me down them. So I wove my way out of Calabria and into Basilicata.

Even for a part of the world where poverty is endemic, Basilicata, or Lucania as it was known until quite recently, is poor. Its glory days had passed with Magna Graecia, 3,000 years ago. Physical isolation, malaria, cholera and earthquakes kept the region in thrall until the 1960s. Its food – pork, lamb, kid, bread, pasta, pulses, salt cod – is specified by poverty, by the mountains that made up the greater part of the province, and by the seas that fringed it to the east and west. On the western side, up which I was travelling, the mountains end in gigantic natural flying buttresses, which drop vertically for a couple of hundred metres to the aquamarine sea. The road followed the line of the buttresses, apparently tacked on to them like a string of beads on the backside of an elephant.

Presently, at Marina di Maratea, I passed a scruffy side road with a battered handwritten sign that read ‘Al Mare’. Why not? I thought. It was a day to be beside the seaside. We turned off, Ginger and I, bounced down the track, passed a trattoria, and went over the coastal railway line to a small headland covered in umbrella pines and that characteristic Mediterranean green-grey scrub of broom, juniper and laurel. On either side of the headland were two small pebble-beached coves, apparently deserted.

Parking Ginger in the shade, I scrambled down to the further of the two coves. The sun winked and twinkled on the scarcely moving water. The harsh, ammoniac smell of rotting seaweed and flotsam mixed with fragrance of thyme and the spicy bush growing on and around the walls of the cove. The sea bed wobbled and rippled through the lapis lazuli water. I had been following the line of the Tyrrhenian Sea all these weeks and not so much as put a toe into it. It seemed silly not to have a little paddle.

I took off my boots and socks and rolled up my trousers. The water was pleasantly cool. The reflected sunlight shifted easily over the surface of the rocks. The winking light off the sea was mesmerising. Well, why not have a swim? Checking the high ground for potential voyeurs, I stripped to my underpants and slipped into the water. It was gently refreshing, and the sun was warm on my head. I paddled round and then eased myself out on to a rock and lay like a fat, white seal in the sun. And then the pagan spirit of the place took hold and I shed the last vestiges of civilisation and swam naked.

This is it, I thought. This is how I had imagined it would be.

That night, over an indifferent dinner at La Locanda delle Donne Monache – the Locanda of the Nuns – a suave hostelry made over with glossy, Provençal-style rusticity, in Maratea, I finally finished Old Calabria by Norman Douglas. Douglas’s voice had kept me company, chattering away incessantly during solitary meals, mornings and that last half hour before lights out. And what an invariably diverting, amusing, learned, kindly voice it was.