По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

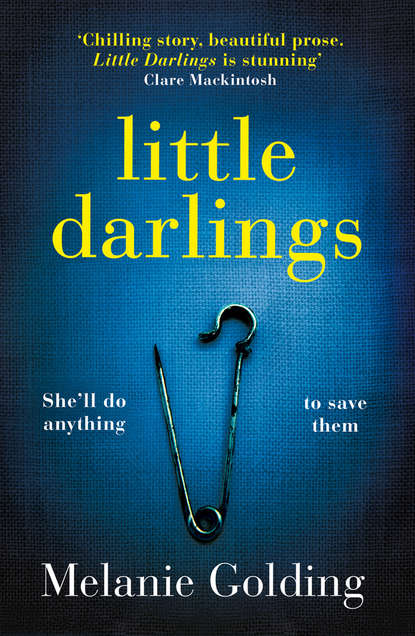

Little Darlings

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Patrick looked up from his phone. ‘Oh, I, sort of already did.’ The phone started pinging with notifications as comments came in. He tilted the screen to show her:

Congratulations!

Glad you are all well!

Hope to see you soon!

Soooo beautiful!!!

Wow well done you guys can’t wait to meet the boys Xxx!

Later she took matching photos of him, holding the twins while he sat in the vinyl-covered armchair next to the bed. His appearance was just the same as always. Maybe he seemed a bit tired, perhaps as if he had a mild hangover, but there was no radical change. He’d lost a tiny bit of weight recently and people – friends of theirs – were saying how much better he looked for it. Where was the justice in that? They were both parents of twins now but it was her body that had been sacrificed.

Patrick put both babies back into the cot. He was handling them with less trepidation than before, putting them down as if they were fruits that bruised easily rather than explosives that needed decommissioning. He sat down but he kept one hand in the cot with them, counting fingers, self-consciously trying out nursery rhymes he could only half remember.

‘Round and round the garden, like a dum de dum. Like a . . . what is it like?’

‘Like a teddy bear,’ said Lauren.

‘Is it?’

‘Yes. I think so.’ She pictured her mother’s finger, tracing circles on her palm. The anticipation of the one step, two steps, tickle you under there. More rhymes came to her then: Jack and Jill, Georgie Porgie, a blackbird to peck off a nose. It was like lifting the lid on a forgotten box of treasure. These gifts, not thought of for years, there in her memory all this time, waiting for her to need them, to pass them on.

‘Teddy bear?’ said Patrick, still sceptical. ‘Well, that doesn’t make sense.’

Lauren put her hand in the cot, too. She stroked Morgan’s cheek and for a few seconds there was peace. It was such simple joy to feel the grip of a miniature hand around your thumb.

‘Are they breathing?’ said Patrick.

A sudden panic.

‘Of course they are.’ Were they? They both stared hard at the boys’ chests but it was difficult to tell. She tickled them in turn until they cried, voices twining together, so similar to each other, the two sounds in parallel like twisting strands of DNA.

‘Yes, they’re breathing.’

They laughed nervously, relieved, as if they’d come close to something unspeakable but not close enough to say what it was. The ground was shifting under them. What would life look like, now?

The anaesthetist came and poked Lauren in the swollen ankles with a pointy white plastic stick. She dangled her legs so he could test her reflexes with the hammer end. She could feel it fine. It was a relief to be paraplegic no longer.

‘You should be able to get up now,’ he said. ‘The nurse will come along soon to remove your catheter.’

She’d miss that catheter. For months she’d been up seven or eight times in the night to empty her oppressed bladder. She quite liked not having to think about it – not being at the mercy of yet another uncontrollable bodily function.

‘When can I go home?’ She was sweating in the dry heat, the skin on her lower limbs stretched shiny with the swelling. Why was the heating even on in the summer? The hottest summer Sheffield had seen for forty years. Apart from anything else, what a waste of money.

The anaesthetist looked at her notes.

‘Well, I can safely discharge you once you’ve moved your bowels.’

‘Moved my—’

‘Bowels?’ The doctor smiled indulgently at her.

She’d understood, but the term was unfamiliar. Not much mention of bowels in her former life sculpting moulds for garden ornaments. No one ever ordered bowels cast in concrete with a fountain attachment for their garden pond.

Though the talk was of catheters and bowels, she bathed in the doctor’s easy confident manner and was sad when he went away again, leaving her trapped in her little family unit, her perfect four. Patrick made a little whistling sound at Lauren as she gazed moonily at the doctor’s retreating back.

‘What?’ she said.

‘I thought you went for tall men.’

She laughed darkly. She was thinking of that moment again, when the needle went in and the pain went away and the anaesthetist carved a place for himself in her heart, made of gratitude and respect and a little bit of girlish adoration.

‘You should have a walk around now, check that everything’s working fine.’

The nurse had taken out the catheter only ten minutes before and Lauren felt slightly aggrieved by the abruptness of the suggestion – one moment a bed-bound dependent, the next dragged out and forced to march around, quick smart hup-two-three. She hadn’t used her legs at all in twenty hours. They needed time to think about it. No part of Lauren liked being expected to perform at short notice.

She planted her two fat bare feet onto the cool vinyl floor, feeling the many specks of grit on its surface. The nurse gestured to Patrick to take the other arm.

‘Oh Jesus,’ said Patrick as he helped her stand up.

She twisted to see. A puddle of blood on the white sheet almost the width of the bed, a red sun. Oh, thought Lauren, it’s just like the Japanese flag. And then she felt it, rivulets down the inside of her legs, pooling on the floor, red and black and hot like the fear.

After the birth, Lauren was convinced that nothing could be as awful. But towards the end, when they’d decided forceps would be needed, the worst of it had been performed behind a screen of drapery and anaesthetic. She’d not seen or felt the whole of it, not even a significant percentage of it. Where was the lovely anaesthetist now, now that she had a further stranger, a medical person (who could actually be anyone at all, some goon off the street in a costume and how would she even know) inserting a whole hand into her and squeezing her womb until it stopped bleeding? One blue-gloved hand (‘Gloves, Mr Symons?’ ‘Do you have Large?’ Oh God.) on the inside, one pushing down from the top and nearly disappearing into the spongy mass of stomach flesh created by the absence of the babies.

‘Just try to breathe,’ said the person (a doctor, she hoped). An older man this time. ‘This shouldn’t hurt too much. Tell me if you really need me to stop.’

‘I really need you to stop.’

The person/doctor did not stop. A nurse gave her nitrous oxide. Lauren bit down on the mouthpiece and spoke through her teeth, ‘Please stop.’

‘Just relax if you can. I need to carry on applying pressure for a few minutes longer. The bleeding has nearly stopped. Breathe slowly. Try to relax your legs.’ He was grunting with the effort.

‘Oh,’ said the nurse, as a sharp pain distracted Lauren momentarily, a hot feeling of flesh unzipping around the man’s forearm. ‘We’ll have to do those stitches again.’

‘Please—’ Her voice caught in a sob, but there was no energy for crying. ‘Please. I can’t. It really hurts.’ The hand inside her shifted horribly. She cried out.

‘Just a minute longer.’

And she kept the terrible silence for as long as she could, unable to fight or fly, a strange man’s hands compressing parts of her body that she would never see or feel with her own. Not just in her but through her, further inside than felt natural, or right. She was a pulsating piece of meat full of inconvenient nerve endings and un-cauterised vessels. No intrigue here, no mystery, no power. She’d been deconstructed by nature, and then by man, then nature again, and finally by man – the two forces tossing her hand over hand, back and forth like volleyball. Where was Lauren in this maelstrom of awfulness? Where was the person she had previously thought herself to be? Intelligent, funny, in control, that Lauren. She’d been hiding as best she could, sheltering in the back of her psyche somewhere, allowing the least evolved part of her instinctive self to be the thing that was present in this trauma. Disassociation, the word like a mantra within her silence as the older man withdrew his hand with exaggerated carefulness, the nurse took away her gas and air and inserted a needle for a drip in the back of a hand so pale she barely recognised it as her own. She was flaccid, weak, beaten. She was all shock and pain and sorrow.

Patrick was waiting, trying to comfort the screaming twins by poking his pinkie fingers in their mouths.

‘You scared me for a minute there,’ he said, his voice only decipherable over the din because of its low register.

She couldn’t think with the crying – the interference caused her mind to fill with white noise. She made an effort to form a sentence, her language processors struggling uphill in the wind against her reptilian brain.

‘You were just afraid I’d leave you alone with these two.’