По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

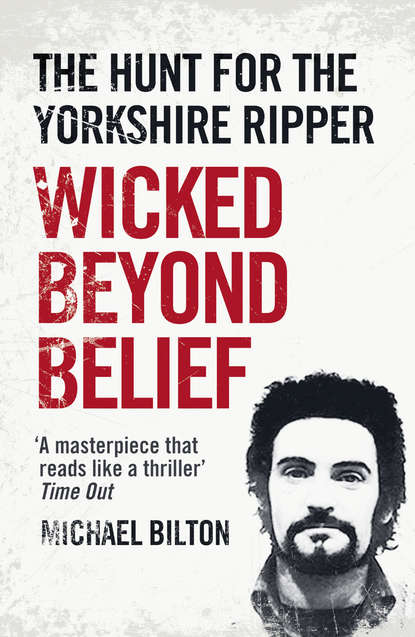

Wicked Beyond Belief: The Hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But when the Yorkshire Ripper case concluded five years later in 1981 it was abundantly obvious that Britain’s chief constables, and the police service as a whole, had disastrously failed to learn the lessons of the Black Panther investigation. Government ministers, senior officials at the Home Office and the Government’s law officers saw little merit in an agonizing public debate over the Yorkshire Ripper investigation. MPs’ demands for transparency were turned down, and there would be no public inquiry. But there was a major shock in store for the criminal justice establishment when Sutcliffe’s trial opened at the Old Bailey in London.

The prosecution, led by the Attorney General, Sir Michael Havers, pushed for a suspiciously speedy hearing, accepting a guilty plea to manslaughter from the accused, Peter Sutcliffe, on the grounds that mental illness had diminished his responsibility for his crimes. It all seemed done and dusted. The court proceedings would be over within half a day because both defence and prosecution were in complete accord.

However, they had not reckoned with the Judge’s reaction. To his very great credit Mr Justice Boreham refused what was in essence a plea bargain. Instead he ordered a full and open trial by jury to determine whether Sutcliffe was mad or bad. The jury would hear the evidence and decide for themselves whether Sutcliffe was guilty or not guilty of murdering thirteen women; or was guilty of manslaughter because he did not know what he was doing. Justice demanded that this gravest of matters should not be swept under the carpet. Ultimately he was convicted and given a thirty-year minimum sentence.

It seems extraordinary that nearly thirty years later the arguments about Sutcliffe’s responsibility for his crimes had never gone away. A new team of lawyers came back with a vengeance in 2010, when the Yorkshire Ripper went to court saying that having served his minimum sentence, he was entitled to know when he would be released. For the public at large the very idea seemed preposterous, incredible even; but Sutcliffe’s psychiatrists at Broadmoor secure hospital had declared their great success in treating him and were arguing that all along he had suffered from mental illness, meaning that his responsibility was diminished when he committed his crimes. Sutcliffe’s lawyers argued this meant he was entitled to a reduction of his minimum sentence.

All this was made possible because the European Court of Human Rights in 2002 ruled that judges – not the Home Secretary – should decide how long a lifer spends in gaol. So once again Peter Sutcliffe stood at centre stage making headlines, once more his activities invaded the psyche of the British public, fearful that the courts might actually believe he was almost an unintended victim of the Ripper case and set him free. Politically, the very idea was quite toxic, and the Prime Minister and Justice Secretary were both put on the spot, as an anxious public demanded to know: ‘Is this man actually going to be freed?’

Dealing as it did with one of the most notorious killers in British criminal history, the Yorkshire Ripper case raised crucial questions. Before her death, Myra Hindley – the 1960s Moors murderer of several children – had routinely tested the patience of the public with her woeful cries that she had served her time. Now another notorious serial killer was following suit. Thirty years before, the thought that Sutcliffe would ever be freed would have seemed utterly fanciful. Then Britain woke up and found that three decades had slipped by, the thirty-year minimum sentence passed at the Old Bailey in May 1981, was almost at an end – and now the law was different.

After Sutcliffe was snared in January 1981, there were enormous issues raised which needed truthful answers, especially about the failure of the police to solve very serious crimes. Today, such matters would be openly debated and inquiries held. But back then the public at large, the families of the Yorkshire Ripper’s victims, the media, the taxpayers of West Yorkshire, MPs, even seasoned high-ranking detectives closely involved in homicide investigations, were never given answers. The key questions had been: Why did it take so long to catch this terrible serial killer? Had the police been up to the task? Who should be held accountable for mistakes that were made? The reason for this was the huge sensitivity surrounding shocking errors in the investigation.

Sutcliffe’s official toll was thirteen dead and seven attempted murders. We now know that he attacked many more women and that there were many opportunities to apprehend him which were tragically missed. In recent times, public disquiet over the Stephen Lawrence murder in London and the multiple killings by Dr Harold Shipman resulted in full and transparently open inquiries. In contrast, public disquiet over the Yorkshire Ripper investigation was flatly dismissed with platitudes that everything would be better in future. No open inquiry took place. Serious questions were posed but the answers only emerged behind closed doors. A high-level secret inquiry had recommended revolutionary changes in the way the police investigated serious crime, and yet openness, transparency and the acknowledgement that the public had a perfect right to know the truth about the police hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper were nowhere to be seen.

In January 1982, seven months after Sutcliffe was given twenty terms of life imprisonment, the then Home Secretary appeared before Parliament to announce the findings of an internal Home Office inquiry by one of Britain’s most senior and respected policemen, Mr Lawrence Byford. He had brilliantly investigated what went wrong with the Yorkshire Ripper case, but William Whitelaw, the Home Secretary, refused to publish Byford’s penetrating report which stripped bare all the mistakes that were made. Instead a brief four-page summary of its main conclusions and recommendations was placed in the House of Commons library. This summary only scratched the surface of the body of crucial facts garnered during Byford’s six-months-long inquiry by an eminent team of senior British police officers and the country’s leading forensic scientist, which was a model of its kind.

In a quiet and unsensational way, Byford’s report laid out its unvarnished and unpalatable truths in more than 150 closely typed pages. It contained much extraordinary detail. Such was the confidentiality surrounding the report that it was printed privately outside London and not by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. No senior civil servant, not even the Permanent Secretary to the Home Office, was allowed to view a copy until Mr Byford delivered it personally to William Whitelaw. As one of Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Constabulary, Byford knew that in preparing the report he and his inquiry team had a grave duty to perform not merely for the benefit of the police service, but for the country as a whole.

Byford and his team did not shirk their responsibility. The changes his report recommended were truly ground-breaking, so much so that a cynic might say that if there had been no Yorkshire Ripper, it might have been well to invent him, as the sole means to force dramatic but profoundly necessary changes upon a creaking police service.

As a staff writer for the Sunday Times based in Yorkshire from 1979 to 1982, I became closely acquainted with some of the detectives, pathologists, forensic scientists and outside advisers who were most closely involved in the Ripper case. Over the succeeding years many of the figures principally involved in the investigation spoke to me off the record about their work on the Ripper Inquiry and how it personally affected them. Some, like Dick Holland and George Oldfield – key members of the Ripper Squad – went to their graves feeling they had been scapegoated. Others felt their actions and motives were totally misunderstood. Until I had got my hands on a copy – some seventeen years after it was written! – the Byford Report had remained an official secret. It was not till the summer of 2006 that the Home Office at last released the report and some of their own files, following an application under the Freedom of Information Act. Britain’s most senior detectives, those with responsibility for investigating major crimes, had not been allowed to study this vital account of what had gone wrong.

I read the Byford Report for the first time in 1998, and realized that here was a sensational story. Answers now fell into place. All too many mistakes had been made, and a good number of those closely involved with the most important criminal investigation in British history agreed that the full story deserved to be told so that the British public – and more urgently, future generations of detectives – could learn its lessons. Hence this book.

For me the real story was as thrilling and chilling as any crime novel, containing as it did such complex characters and so many twists and turns. The more I got to know the detectives the more fascinated I became by who they were – and why it was that some of them had got it so disastrously wrong. These were not one-dimensional figures, and I endeavoured, as I wrote the narrative, to put flesh and bones on some of them so that they could be seen for what they were, human beings trying to do a difficult job.

Some were clearly better than others, but I have no intention of pillorying anyone for mistakes that were made. As a writer you cannot examine how an institution works and forget the very people who make up that institution. When the institution fails you need to look at its whole structure, which in the case of the police service starts with ordinary policemen and women on the beat and progresses upwards through a hierarchy, beyond the chief officers, to the Inspectorate of Constabulary, the Home Office civil servants in the Police Department, and then the ministers in charge, ending with the Home Secretary.

You had to live in the North of England to comprehend how such a terrible series of crimes terrified a major part of the British Isles. Still today, what most people want to know is: What went wrong? Why did it take so long to catch Peter Sutcliffe?

Even thirty years later, and allowing for the benefit of hindsight, some of what has emerged about the investigation seems truly shocking. As with other notorious murder cases, when the subject of the Yorkshire Ripper is mentioned it brings dreadful memories flooding back for those most intimately involved. The families of Sutcliffe’s victims deserved to know what really happened during that awful period when a beast called Peter Sutcliffe roamed the North of England creating outright terror. They also needed to know that some good came out of that terrible era and that lessons were learned about complex cases.

The police officers trying to track down this utterly ruthless killer were decent and honest men. Amid the chaos that gripped the investigation there were some brilliant detectives. Most were totally committed, but tragically some, just like the police service for which they worked, were way out of their depth. The British police have an extraordinary record in solving homicides, and G.K. Chesterton’s reflection that ‘society is at the mercy of a murderer without a motive’ is now only partially true. Random prostitute murders are still every senior investigating officer’s worst nightmare, but in recent times we have seen successful investigations into the serial killing of call-girls in Suffolk and a fresh round of prostitute murders in Bradford. It is very different now from that period in the last century when the hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper was so complex and protracted that it simply overwhelmed the West Yorkshire Police. Many of the detectives involved paid a high price – ruined careers, ruined health, ruined marriages – and in a few cases it led to their premature deaths.

Now as then, I am not remotely interested in Peter Sutcliffe, the individual. Many have asked whether I ever wanted to interview him. The answer was a resounding. ‘No!’ What could he tell me that I didn’t already know – that he was a sick and perverted killer who got powerful sexual thrills from having women at his mercy as he slaughtered them? For me it would have been a worthless exercise to ask Sutcliffe serious questions and expect believable or valuable answers. The detectives though were another matter completely. I was intrigued by them as people, and by the service for which they worked. I wanted to put the reader in their shoes, as they attended a murder scene or an autopsy or a press conference. There can be no freedom without a system of laws and we need these dedicated men and women to enforce those laws. The British police service remains one of our pivotal institutions; it safeguards much of what we take for granted.

More than three decades after attending his trial in Court Number One at the Old Bailey in May 1981, I resolutely maintain that there was only a single villain in the Yorkshire Ripper case. It was, and is, the monstrous and twisted individual I saw giving evidence in his own, highly implausible, defence of the indefensible. Peter Sutcliffe was, and remains, wicked beyond belief and it will come as a comfort to many that some of our most senior judges, led by the Lord Chief Justice himself, seem to agree with me.

Michael Bilton, January 2012

1

Contact and Exchange

Exactly twenty-nine minutes after the body of Wilma McCann was found, the telephone rang beside Hoban’s bed. It was at 8.10 a.m. Early-morning calls were nothing new for the head of Leeds CID. He had been sound asleep for nearly an hour, having crawled between the sheets next to his wife, Betty, not long before dawn. He had been up since 1 a.m. at a murder scene in another part of the city for most of the night. A phone call now was the last thing he needed. The control room at Wakefield was on the line. ‘A murder, sir,’ the operator said. ‘A woman, at the Prince Philip playing fields, Scott Hall Road, Chapeltown. Found by the milkman, sir. The local police surgeon is at the scene already and Mr Craig is on his way.’ Craig! The assistant chief constable in charge of crime was turning out. That settled it – Hoban couldn’t take his time, he wanted to be there before him.

Betty was already downstairs making a cup of tea. She knew what to expect. No point in making him breakfast. He’d be up and off. He’d wash and shave, take his insulin, get dressed. Then he’d be gone. She knew it would be midnight before she saw him again. ‘There’s another murder, young woman this time in Chapeltown,’ he said downstairs in the hallway, kissing her on the cheek and saying goodbye at the same time. ‘Dennis …’ she hardly had time to say ‘take care’ before he was gone. Through the front-room window she saw him reverse his blue Daimler on to the road and drive off. For the umpteenth hundred time in thirty years of marriage, Betty was left alone while her husband went chasing criminals.

A freelance photographer arrived at the playing field before Hoban. The scenes of crime team had not yet put up a tarpaulin screen to shield the body from prying eyes. A uniformed officer prevented the freelance going any further. A 500 mm telephoto lens was clipped on to his Nikon camera. Looking through the eyepiece, he could clearly see one hundred yards away the body of a woman on its back, trousers above her ankles. Just then several figures moved into the framed image from left and right. Two uniform constables from the area traffic car were dragging a crude canvas screen closer towards the woman. And just then, moving slowly into frame from the right, the scenes of crime photographer arrived with his large plate camera already clamped on to its tripod. The freelance had only seconds to take the shot before the body was obscured. His shutter clicked and almost immediately the camera’s motor-drive whirred and wound on. A pathetically sad image of a murder victim in the morning mist was captured for all time on 35 mm film.

More newsmen turned up. Film crews from the local television stations; reporters from the Evening Post. There was some relief for the waiting journalists when Hoban arrived, clearly identifiable in his light-coloured raincoat, belted at the waist, his brimmed hat hiding his receding hairline. There was an almost symbiotic relationship between them and the local CID chief, and so a formal ritual was played out. They would wait patiently, perhaps go door-knocking to see if any local neighbours knew what happened. He’d do what he had to do, then help them. Those in search of a story and pictures needed the goodwill of the man in charge. They had to be patient and not take liberties, not impinge on the investigation. To solve this murder, any murder, Hoban knew he needed information from the public. The media were a valuable resource, so he’d personally make sure they got the story in time for the first edition of the Post and the first news summary on the local TV stations at midday.

Formal greetings with his colleagues were just that. Formal. It was cold. There was low-lying fog. The men around him stamped their feet, arms folded against their chests, trying to keep warm. Some had been waiting at the crime scene for nearly an hour since the woman was found at 7.41 a.m. by the passing milkman. The date was 30 October 1975, the eve of Halloween and only days to go to Fireworks Night. It was that time of year when local kids had been making effigies of Guy Fawkes, standing on street corners, asking ‘Penny for the Guy’. The local milkman was making the early-morning round with his ten-year-old brother. Mist hanging over the area made it difficult to see properly as Alan Routledge drove his electric-powered milk van into the rectangular tarmac car park of the Prince Philip Centre. He got out to deliver a crate of milk and there, on a steep banking on the far side of the car park, near the rear of the caretaker’s house and the sports field clubhouse, spotted what he at first thought was a bundle of rags or perhaps a children’s ‘Guy’. Out of curiosity the brothers edged closer. It was the body of a woman. Routledge ushered his sibling away and ran for a phone. He told the police operator he had found a woman with her throat cut.

The uniformed officers laid down a series of duckboards across the grassy area to the murder scene. Hoban moved forward, treading carefully on the slatted wood. Devlin, the police surgeon, greeted him. The woman lay on her back, at a slightly oblique angle across the slope, the head pointing uphill and the feet directed towards the edge of the car park. Her reddish-coloured handbag lay beside her, its leather strap still looped around her left hand. Her white flared slacks had been pulled down below her knees; both her pink blouse and her blue bolero-style jacket had been ripped apart. Her bra, a flimsy pink-coloured thing, had been pulled up to expose her breasts. Blood from stab wounds had leaked over to the right side of her body. The blood had dried. More blood from a stab wound on the left side of her chest trickled down to the edge of her pants, obviously, thought Hoban, because her feet were pointing downhill. Her auburn hair had been backcombed into a beehive style high above her head, but now much of it was spread out on the grass. She had worn a pair of shoes with an inch-thick sole and a four-inch heel. Her knickers were in the normal position covering her genitalia. They bore a large, colour printed jokey motif, part of which Hoban could easily read without bending down: ‘Famous meeting places’. A small button lay behind her head and some coins were in the nearby grass. The wounds were divided into several areas: a stab wound to the throat; two stab wounds below the right breast; three stab wounds below the left breast and a series of nine stab wounds around the umbilicus.

By the time the local Home Office pathologist arrived at 9.25 a.m. Hoban knew the dead woman’s name and the fact that she lived barely a hundred yards away. The back entrance to her council house in Scott Hall Avenue opened out on to the playing field. Neighbours told officers making house to house inquiries how Wilma McCann lived with four young children, separated from her husband. Two of the children had gone looking for their mother at first light when she failed to return home, after having left the eldest, Sonje, aged nine, in charge. Sonje and her brother went to wait at the nearby bus stop to see if their mother had caught an early-morning bus home. They were standing there freezing when a neighbour found them with their school coats over their pyjamas.

Nothing surprised Hoban any more, he’d seen all this before. Desperate women. Children neglected. Leeds City council officials had already been alerted that the four McCann children would almost certainly need foster care. No one knew at first where their father lived. Initially, because Wilma was found so close to her home, Hoban considered that this might be a domestic incident that got out of hand. Perhaps the former husband was involved. Then he heard that Wilma frequently went out at night to the local pubs and clubs to ‘have a good time’ – and she got paid for it. Like many single mothers on the breadline, she slept with men for money. She came and went via the back entrance to hide the fact that she left the children alone for several hours and frequently returned late at night. For this she had paid the terrible price. Although she had no convictions for prostitution, Hoban knew the fact that she was a good-time girl would be a major complication.

Standing there that morning, he hoped and expected they could solve this case quickly. The victim would surely have some relationship to the killer – a motive would be established and with luck and a fair wind they would have their man. The other senior man to arrive at the McCann murder scene was the forensic pathologist, David Gee, who knew Hoban well and admired his professionalism as a top detective. Each had earned the respect of the other. They had already spent most of the night together at the scene of another murder elsewhere in the city and Gee also had only just dropped off into a very deep sleep when the phone call came through alerting him to this latest case. Not unreasonably, he regarded it as a bit of a nuisance. He had made good speed, considering he had to drive in to Leeds from Knaresborough, twenty miles away, during the morning rush hour. Hoban filled him in on all he knew so far. Gee – notebook in one hand, biro in the other – stood as he always did, listening intently. For a few minutes he looked at and around the body. Eventually he drew a diagram and wrote a few cryptic remarks. For a murder involving multiple stab wounds it was what he would have expected. There was heavy soiling of the skin at the front and right side of the neck because of the stab wound on the throat. Blood was staining the grass beside the victim’s head. The blood trickling from the chest and abdomen had also soiled the right side of the victim’s blouse. Other spots of dried blood could be seen on the front of both her thighs, on the upper surface of her slacks and the upper surface of her right hand.

Gee’s very first thoughts were that the blood seepages running vertically downwards from the stab wounds in all directions suggested she had been stabbed to death where she lay. One blood trickle ran into the top of her knickers and then along it. When the panties were removed, he could see the trickle did not run down inside, probably indicating that no sexual intercourse had taken place either just before or just after the stabbing. Some blood soiled her long and tangled hair, but this was maybe due to blood escaping from the wound to her neck.

Once the body had been photographed, Ron Outtridge, the forensic scientist from the Home Office laboratory at Harrogate, moved closer and began taking Sellotape impressions from the exposed portions, hoping to find tiny fibres, perhaps from the killer’s clothing. Gee took swabs from various orifices – vagina, anus, mouth. Then he began measuring the temperature of the body at roughly half-hourly intervals. In an hour, between 10.30 and 11.30 a.m., Wilma’s corpse grew colder by two degrees, falling to 71.5°F. However, once the sun came up, the external temperature began to rise. By a simple calculation Gee determined that death happened around midnight, according to the hourly rate at which the body dropped in temperature. A gentle south-westerly breeze eventually blew the fog away and by 11.40 the temperature was 59°F, quite warm for an autumn day. The sky, however, remained overcast and there were a few spots of rain. For protection, the body was partly covered by a plastic sheet raised above the corpse on a metal frame so as not to contaminate any clues. By this time there was slight rigor mortis. Outtridge then removed the slacks, shoes and handbag. Plastic bags were placed over the head and hands and the body was gently wrapped in a much larger plastic sheet for the short journey by windowless van to the local mortuary. There the rest of the clothing was removed and handed over to Outtridge. A fingerprint specialist examined the body for prints on the surface of the skin.

The team, including Hoban and Outtridge, gathered again for the formal post-mortem at 2 p.m. It was a long and exacting process which took four hours. Most officers hate post-mortems. ‘It is not only the sight but the smell of the body and the disinfectants,’ recalls one senior detective who had been involved on countless murder inquiries. ‘The smell would cling to your clothing and when I got home I would strip, put clothes in the washer and my suit on the line. I would then have a shower but I would also lose my sex drive for several days. I think a lot of policemen are affected in this way.’

After the formalities of measuring and weighing the body, Gee quickly made an important discovery. Because Wilma had been lying on her back when found, there had been no examination of the rear of her head. On the examination table, her head propped up on a wooden block, he quickly located two lacerations of the scalp that had been concealed by her long hair. One was a vertical and slightly curved laceration, two inches in length, its margins relatively clean cut and shelving towards the right. This wound penetrated the full thickness of the scalp and through it a deep fracture in the skull could be clearly observed. Two inches to the left was another head injury, not so severe. Gee pointed out the two wounds, and later this portion of Wilma’s skull was shaved so they could be photographed prior to her brain being removed and studied.

Gee then began minutely examining the fifteen stab wounds to the body, trying to follow the track of each beneath the surface of the skin. It was a difficult task. The majority of wounds to her abdomen were very close together. It proved impossible to show the direction of each individual track of each individual wound. He had greater success in tracking the wounds to the neck and chest. Here, patiently, slowly, was a scientist methodically at work trying to learn what kind of weapon or weapons had been used to kill Wilma; and to determine more precisely how she actually died.

Gee’s final conclusion was that death occurred within minutes of the victim being struck on the head, then stabbed. He believed the weapon involved in the stabbing was more than three inches long and a quarter of an inch broad. She’d been hit on the head with a blunt object with a restricted striking surface. It could have been a hammer, but at this stage Gee favoured something like an adjustable spanner. There was nothing special about the stab wounds. The victim had been struck from the left side. Death had occurred probably early on the morning of 30 October.

Back in his office later that night Hoban began absorbing the information flowing in. House to house inquiries by the Task Force began to give a more detailed and increasingly depressing picture of Wilma’s lifestyle. Her former husband had been traced. Her parents were contacted in Scotland. Criminal records showed she had four convictions for drunkenness, theft and disorderly conduct. The local vice squad believed she was a known prostitute, though she had never been cautioned.

Wilma had been born and brought up near Inverness, one of eleven children. Her father was a farm worker. She had been christened Willemena Mary Newlands. According to her mother, she had been a good speller as a child, full of life but inclined to go her own way. Mrs Betsy Newlands said she had brought up all eleven children strictly. Wilma had to be in bed by 10 p.m. every night and when her father discovered her wearing make-up he took it from her and buried it in the garden. She could quickly become emotional, and when she did everyone would know about it. From leaving the local technical school she went to work at the Gleneagles Hotel near Perth. She had been pregnant with her daughter, Sonje, before she was out of her teens.

After Sonje was born, Wilma met a joiner, Gerald Christopher McCann from Londonderry, Northern Ireland. They married on 7 October 1968. A few years later they moved to the Leeds area, where five of Wilma’s brothers lived. She and Gerry had three children of their own in fairly quick succession – a son and two daughters. But by February 1974 the marriage was over. Wilma couldn’t settle, she hadn’t the self-discipline to adapt to either marriage or motherhood. She liked her nights out. And she liked other men. Gerry left and soon took up with another woman and had a child by her. He continued to see his kids after school and bought them birthday presents, Wilma did not ask for money from National Assistance but earned it her way – when she went out in the evening. Gerry McCann wanted a divorce on the grounds of his wife’s adultery and Wilma was happy to give it to him. Court proceedings were imminent.

From early on after Wilma and Gerry separated, nine-year-old Sonje seemed to be doing most of the caring for her half-brother and half-sisters at the house. In fact Wilma came to rely increasingly on the little girl, who was expected to grow up quickly and take on board responsibilities for her siblings way before her time. As a mother, Wilma was hopeless. She had degenerated into a terrible drunken state. The house, when police searched it, was filthy. She was sexually promiscuous and irresponsible and Gerry, a caring father, had become increasingly concerned that, since their separation, Wilma was neglecting the children’s welfare and leaving them alone for long periods in the evenings.

Hoban knew inner-city Leeds intimately. He had worked there for thirty years, he knew the streets, he knew the back alleyways, the pubs and clubs. He met his vast network of informants there – the criminal classes who gave him tipoffs that made him probably the best-informed detective in the city. He knew the wide boys, the spivs, the con men, the burglars, the pickpockets, the whores, the fences. He also knew the serious criminals, the ones who thought nothing of taking a shotgun on an armed raid on a bank or post office. He had, over the years, locked up hundreds of criminals and earned himself a fierce reputation. Newspapers referred to him as ‘Crime Buster’, or more particularly as the ‘Crime Buster in the sheepskin coat’ – a fitting reference to Hoban’s liking for sartorial elegance in the city responsible for making the made-to-measure suits that clothed half the male population of England through chain stores like Hepworth and Montague Burton.

Hoban’s extraordinary gift for solving crime and his energy and dedication had marked him out from the beginning of his police career. Commendations from magistrates and judges at the assize courts and quarter sessions came thick and fast. There was an inevitability about him rising to the top. He could move easily among those who skated the line between what was legal and what was not. He would drift into a pub or nightclub and soon there would be an exchange of glances as he clocked one of his snouts, some thief, vagabond or ne’er-do-well with information to sell. Thirty seconds apart, they would make for the gentlemen’s lavatory where a ten-shilling note was exchanged for a piece of paper or a discreetly whispered conversation.

Hoban was not a great drinker. His diabetes put paid to that. But he enjoyed social occasions and he loved the status his job gave him. He thrived on working his way up from humble origins to the top, to being a Citizen of the Year in Leeds. And he luxuriated in his work as a police officer. It wasn’t a job, it was a way of life. It was like a drug. He knew it. Betty knew it. His two sons knew it. And murder was his greatest professional challenge. Finding the person or persons who had snuffed out the life of some undeserving man or woman from among the half million souls who lived in the city of Leeds – that took some doing. And Hoban was very good at it. He had been involved in almost forty murders and solved them all.

The day Wilma’s body was discovered and the hunt for her killer launched, Hoban returned to Betty at midnight, his mind troubled by the fact that Wilma McCann, because she persistently had sex for money, might not have known the man who killed her. In these situations the search for an individual who killed with frenzied violence was a top priority because they were such a danger. The early stages of a murder inquiry took precedence over almost everything. The following morning he was due to undergo firearms training on a local range. Before Hoban drifted off to sleep he had to remind himself he must contact someone and cancel the appointment.

For the next week, apart from Sunday, Hoban worked until midnight every day. On the Sunday he went in an hour later, working only a twelve-hour day, so he was home that night shortly after ten o’clock. Wednesday he took off and spent the day with Betty. He tried to be home by 10 p.m. if he could, but frequently it was impossible. Occasionally other crucial duties as the head of the city’s Criminal Investigation Department demanded his time which took him away from the murder inquiry, such as briefing the assistant chief constable, Donald Craig, or a conference with prosecution counsel in connection with other cases destined for trial. But Hoban, once these appointments were out of the way, kept himself and his officers hard at it. He made frequent appeals through the press and on local radio for people to come forward with information. He needed eyewitnesses who had seen Wilma, possibly with her killer.

As each detail came in, it was filed in the index system at the murder incident room. This in turn generated more inquiries: men friends, especially previous lovers, to be traced, interviewed and eliminated; vehicle sightings to be checked; follow-up interviews arising from house-to-house inquiries to be actioned, carried out, checked and then more follow-up actions sanctioned. A more detailed picture of Wilma’s movements on the night she died began to emerge slowly. She had left home at about 7.30, telling Sonje that the younger kids were not to get out of bed. She was ‘going to town again’ and would be back later. From 8.30 to 10.30 p.m. she had been in various city centre pubs. About 11.30 she was on her own at the Room at the Top nightclub, in the North Street/Sheepscar area of the city. The last positive sighting of her was about 1 a.m. when two officers in a patrol car spotted her in Meanwood Road. Other witnesses had seen her trying to hitch a lift by jumping out in front of cars, causing them to stop. She was roaring drunk. The laboratory report, while it showed no trace of semen in her body, did confirm she had consumed a hefty amount of alcohol, between twelve and fourteen measures of spirit. Reports came in of a lorry driver who had stopped near where Wilma was seen weaving her way down the road. Initially, there was some confusion, because another lorry was also seen to pull up and an eyewitness saw Wilma engaged in conversation with the driver.

An early search of her home produced an address book and so began the task of locating a large number of Wilma’s clients, though Hoban discreetly told the press they were searching for past ‘boyfriends’. He appealed for any not yet contacted to come forward. To label a victim a prostitute in this situation was unhelpful. Experience showed the public were somehow not surprised at what happened to call girls. Photographs and stories in the press about Wilma’s orphaned children were intended to create sympathy.

A week after Wilma was killed, Hoban had late-night roadblocks set up on the route she had taken when she left the Room at the Top. As a result, the lorry driver who stopped to talk to her revealed he didn’t pick her up in response to her plea for a lift home. She was totally drunk and clutching a white plastic container in which she was carrying curry and chips. He was heading for the M62 motorway, across the Pennines to Lancashire. A day or so later a car driver came forward to say he had seen Wilma getting into a ‘K’ registered, red or orange fastback saloon, looking similar to a Hillman Avenger. The driver was said to be coloured, possibly West Indian or African, aged about thirty-five, with a full face ‘and thin droopy moustache’. He was wearing a donkey jacket.