По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

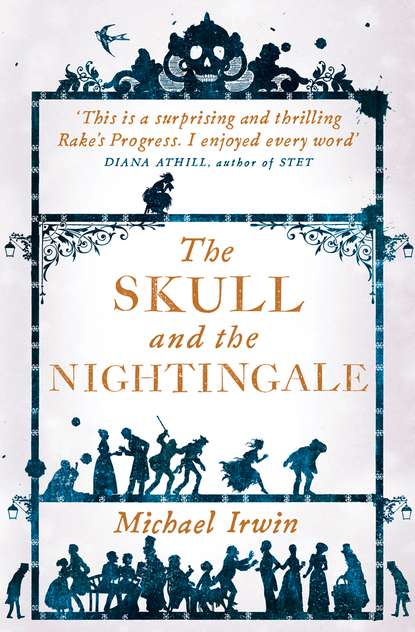

The Skull and the Nightingale

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I have renewed acquaintanceship with two of my Oxford companions, Ralph Latimer and Nick Horn. Latimer is fashionably languid, but harbours serious ambitions. As a relative of the Grenvilles he hopes soon to turn his back on his present freedoms and prepare for a higher role. It is less likely that Horn will seek respectability. He is a small, restless, nimble fellow, who will attempt anything by way of diversion. I have seen him climb a cathedral tower, half drunk, and on another occasion, for a five-shilling wager, wrestle with a pig.

The conversation I enjoy with such friends is livelier than drawing-room chatter, but too often deformed by liquor. Let me offer you a recent specimen, chosen because it recalled to me a discussion at your own table. The hour was late, and we had attained the melancholy mode. Latimer pronounced, with great emphasis: ‘Believe me, friends, there is much in this life to make a man uneasy.’

This gloomy sentiment made us confoundedly grave. The conversation had been raised to a formidable altitude, but one or two of us tried our wings.

‘I am of much the same opinion,’ said a heavy fellow. ‘Can even the best of us survive long enough to learn how to live?’

I myself ventured, with solemnity: ‘Who knows but that one of us, even before the month is out, may be standing before his Maker? Is not that a tremendous thought?’

Latimer, unimpressed, was disposed to be argumentative.

‘You say “standing”, but the word is prejudicial. Can we so confidently assume the existence of legs in the life to come?’

To keep the shuttlecock aloft I improvised: ‘At the moment of Judgement might we not be mercifully permitted some temporary sense of perpen- perpendicularity?’

‘To be followed by what?’ asked Horn.

Intimidated by this dark prospect, we all stared into vacancy, and our speculations expired.

It occurs to me that most people seem to shrink from contemplation of the after-life. Even those who are most earnest during divine service, as though glimpsing eternity, promptly revert to their workaday, unconcerned selves at the final blessing.

I conclude with a further note on the life of the streets. Within five minutes of leaving a polite assembly last evening I saw a man stumbling along with blood streaming from a wound to his head. London life is everywhere precarious. Even when walking to a steakhouse one may be under challenge. Should that shove be reciprocated? Might that urchin be a thief? How remote from the rural life of reflection. Who can philosophize about swimming while compelled to swim? Last week, feeling a tattered pedestrian press too close I flung him from me. On the instant I regretted my reaction, for the wretch went staggering into the dirt. However, his rags falling open and disclosing two fine watches he was seized as a thief and mauled by the mob. My aggression had been justified by the event, but I might as easily have been wrong.

Daily I immerse myself further in the life of the city: I look about, listen and explore. You will soon hear further from me.

I remain, &c.

In adjusting myself to London life I was greatly influenced by a conversation with Latimer. I had asked him whether he knew the whereabouts of our friend Matt Cullen.

‘I do not,’ said he, frowning. ‘But I fear he is a lost man.’

‘Lost?’

‘His prospects have taken a turn for the worse. He was in London last year, but was rarely seen. Then he vanished. Horn heard that he had returned to his native village to contrive a marriage. It seems that he is gone from us – condemned to rural nonentity.’

‘Whereas we who remain …’

Latimer over-rode my hint of satire: ‘I can speak only for myself. I look to become a man of consequence. I cultivate men of standing. I make myself agreeable.’

‘That is candidly said.’

‘So it is. Observe how I speak with a trace of self-mockery to render my complacency acceptable. But truly, young gentlemen such as ourselves are on a slippery slope. We must feel for every foothold.’

‘How will Nick Horn fare in this slippery predicament?’

‘Horn will enjoy himself for a year or two longer and then fall away.’

‘Like Cullen?’

‘Like Cullen, but not as fast or as far. His family has greater means.’

Though he spoke airily it was manifest that he meant what he said. Partly to embarrass him I asked: ‘And what say you to my own prospects?’

I was glad to see that the question made him pause.

‘There I am in doubt. You were always a reserved fellow, Dick, not easily sifted.’

‘I am in your debt to the tune of half a compliment. But tell me, Mr Latimer: does not your ambition deflect you from the pleasures of the moment?’

‘It does not. Strip away my gentlemanly apparel and you would behold in me a satyr-like creature. One day the wise head will be obliged to disown the goatish tail – but not quite yet. There is still some discreet sport ahead.’

I found much to ponder in this exchange. If Cullen and even Horn could fall back so easily then I could plummet out of sight. But there was comfort in the realization that, after all, I did not envy Latimer his security. While he was obliged to fill his days with social visits and petty attempts at ingratiation I was free to roam the foulest streets and drink with porter or pedlar.

My dear Godfather,

Last night, in company with Latimer and Horn, I visited the Seven Stars, in Coventry Street, the resort of some of our lustier men of fashion. To enter its doors was to plunge into cacophony; a herd of young bucks was in full cry, and punch flowed freely. The prevailing mirth had its tart London tang, suggesting that at any moment merriment might become aggression. In particular I happened to recognize among the roisterers Captain Derby, whom I had met briefly in Rome, a tall bully with some reputation as a duellist.

Horn, a seasoned visitor, led us boldly through to a back room, somewhat less crowded and noisy. It was here that I was to make the acquaintance of Mr Thomas Crocker.

How can I convey the appearance of this gentleman? If you saw a painting of his head alone you would think him handsome. He has an open countenance, inclining to plumpness, and an air of animation and quick intelligence. As I came into the room this face took my attention, occupying, as it did, a gap on the far side of the room, as though he were sitting slightly apart from his neighbours. Only at a second glance did I understand the source of this isolation: his body is of a bulk quite extraordinary, even freakish. I have since learned that he is nearly thirty stone in weight. When he is seated on a bench his thighs spread wide, so that he fills the space of two men. Had he not been heir to a notable estate he could have made a living as a prodigy in a fair-ground, along with my friend the frog-swallower.

Despite his physical appearance, however, it was soon clear that his companions regard him as their leader. Without exertion he commanded the room.

I sat quiet, observing the company and contributing little. My attention was caught by a silent man who seemed to be an attendant on the party rather than a participant. He was a lean fellow of middle height, with a pale, bony face and a watchful eye. I exchanged some sentences with him and learned that his name was Francis Pike.

The entertainment took a turn I could not have anticipated. When we joined the company and Horn introduced me, Crocker had been cordial enough but said little. Later he called out to me: ‘Mr Fenwick, I am informed by Mr Latimer that you sing.’

‘After a fashion,’ I replied, somewhat taken aback.

(I have been told that I sing tolerably well, though this is not, I think, a talent that I have ever had occasion to mention to you.)

‘Then this shall be our cue,’ he cried out, ‘for an interlude of music.’

He lunged to his feet, and with a shove thrust back the table, creating space to accommodate a mighty belly. His face seemed slightly swollen now, and shone with perspiration, but in manner he was perfectly controlled. Silence fell, and he launched into song, in a baritone voice that would have graced a public stage:

No nightingale now haunts the grove,

No western breezes sweetly moan,

For Phyllida forswears her love,

And leaves me here to mourn alone …

Here was a strange interlude in a tipsy gathering. The lament, a pastoral nullity, was heard with a respect that the execution indeed deserved. It was an incongruous performance from that huge body, as though an elephant should tread a minuet. Hardly had the applause died down than I was summoned to his side and invited to change the mood by joining him in the edifying ballad that begins:

I’m wedded to a waspish wife

Who shames the name of woman: