По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

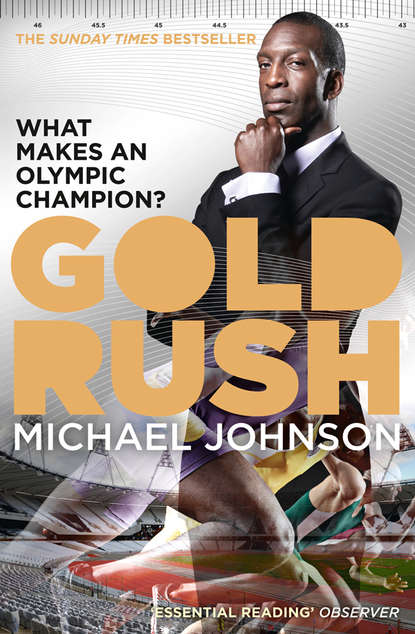

Gold Rush

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Cathy’s quiet and reserve (her words) define the word calm (my word). And yet she’s won gold in two World Championships, four Commonwealth Games and the Olympic Games on her own home turf.

She discovered the Olympics at age ten, while watching a made-for-television movie about American indigenous distance runner Billy Mills, who won a gold medal in the 10,000 metres during the 1964 Tokyo Games. ‘I was at an age where, oh, there’s a runner who’s indigenous and American, and he’s sort of similar to the indigenous people over here,’ Cathy told me. ‘I set in my mind that I wanted to be a runner when I grew up.’ Watching the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games unfold the following year cemented that aspiration. By then, thanks to her stepfather, she already had the words ‘I am the world’s greatest athlete’ posted on her bedroom wall.

That set the bar. ‘In 1990 I made my first Australian team for the Commonwealth Games,’ Cathy told me. ‘Two years later I went to Barcelona. Each year that went by, it became clearer to me where I had to be and what I had to do, the sort of person I had to become.’

TUNING IN TO THE OLYMPICS

A number of Olympic champions fell into their sports and went on to make history. For many, watching the Olympics served as a catalyst. Mark Spitz, who holds a remarkable nine Olympic gold medals in swimming, didn’t join a swimming team because he loved the sport or had been inspired by the Olympics. At least not at first. At the age of nine his mother had put him into a YMCA camp programme just to give him something to do. The problem was that the programme involved arts and crafts instead of sports. Mark, and the friend who had also been put into the camp by his mother, ‘didn’t want to sit around with a bunch of girls doing stupid stuff’. It turned out that a brand new swimming pool had just been completed and programmes would begin being offered the following week.

Mark told me about what happened next. ‘On the very first day in the class that I was in, the instructor said for everybody to line up. They put us all alphabetical and they told us to jump into the pool and hold on to the side. So we were all on the length of the pool and the instructor said, “When I call your name, I want to see how you swim across the width of the pool.” Well, it was a heated pool, but when you fill up a pool, the first day or so, it’s not really heated, so I was freezing my butt off. By the time they got to the S’s all I did was swim across the pool without stopping. Little did I know that the guy who was the instructor of that class was looking to see who didn’t stop. He had set up criteria, unannounced to anybody, that if you didn’t stop he was going to ask you to go out for the swim team. Well, my buddy, his last name was Cooper, got halfway through the width of the pool, stopped and looked at me and was waving and showboating – ‘Ha ha, I got to go first!’ – because that’s what your buddies do, right? So he never got asked to go out for the swim team. There were probably four people in that one session that didn’t stop for whatever reason.

‘So I went out for the swim team. I didn’t know a whole hell of a lot about swimming at the YMCA level. It was designed as a novice programme. At the end of that summer programme we went to a swimming meet. I don’t even remember what I was swimming, but I remember that it was time-based only. My mom took me over to the end of the pool where there were three circles on the deck that said 6-5-4. There was also a little staircase that said 3-2-1. They put me on circle number 5 and handed me a purple ribbon. I looked to my left and I noticed the guy that was on the staircase, he got a white ribbon. The guy on the next step up got a red ribbon, and the guy at the top got a blue ribbon.

‘I came back to my mom crying and gave her that purple ribbon. That was the first time I recognised that I would get a reward for doing something in a sport. I didn’t understand about why I got the reward, or even that someone had given me a time or had a stopwatch on me. The fact was that I didn’t like the purple ribbon because it was quite obvious that that guy on the staircase with the blue ribbon had been treated as more special than I had. I wanted to be on that top stair. How was I going to get there? I had no clue. But I know that to this day I don’t like purple.’

Ironically, Ian Thorpe, who hopes to add to his five gold medals in the 2012 Olympics, also fell into swimming. ‘My sister swam. She only swam because she broke her wrist, so the doctor recommended she swim to strengthen her wrist, but she ended up being quite a swimmer. She made our national team. When I was young, I basically decided I’d take up swimming because I was really bored being dragged along to all these swimming carnivals by my parents to watch my sister.’

Ian already played a few different sports at the age of eight, and it’s probably safe to say that he was better at most of those than he was at swimming. ‘When I was young I wasn’t that good a swimmer,’ he told me. ‘I was allergic to chlorine, as well, and was getting sick from being in the pool. But I enjoyed it. My mum had to take me to the doctor, and basically the doctor said, “Your son’s allergic to chlorine. It has to do with how the adenoids mature in your nose. When he hits puberty it’s not going to be a problem as much any more. If you think he’s going to be a champion swimmer, it’s probably advisable that you have them taken out.”

‘My mother didn’t think I’d be a champion swimmer, so we opted to do nothing and I continued to get sick from swimming from time to time. That took me out of the pool every once in a while. In the pool I had to wear a nose clip, which is probably the uncoolest thing you can wear when you train. But I was like the nerdy swimmer when I was little.

‘My parents wanted me to stop swimming, figuring it wasn’t good for me. But by the time I was ten or eleven I was pretty much winning everything in the pool in the age group competitions. By the time I was 14 I made the national team. I missed every development team on the way because I didn’t meet the criteria. I was usually too young. At 14 I went away on my first trip, which was the Pan Pacific Championships in Japan, and came second. Then, the following year, I was world champion. The year after that I set four world records in four days. Then, the following year, I was Olympic champion.

‘As a pre-teen, my goal was to become an Olympic athlete. I dreamed of winning Olympic gold. At that point, however, I thought maybe Athens would be the first place that I could go and then look at the Olympics after that. My winning the World Championships at 15 was a shock to everyone around the world, and it was a shock to me as well. I’d done things in training that no one else had done, and I was the deserved winner at that race. At the time, however, I just thought I was doing these laps. I didn’t know how it would equate to a performance that meant that I was world champion. I didn’t realise that that win probably meant that I would be favoured to win at the 2000 Olympics. I didn’t even realise I’d make the team.’

TAPPING ONE’S GIFTS

Mark and Ian may have fallen into their sports, but they sure made the most of the opportunity. I believe that everyone, no matter who, is blessed with a natural talent and ability to do something well. It may be running fast like me, it may be overall athletic ability in all sports, it may be mathematics, it may be teaching, it may be an incredible ability to remember and recall things. Maybe it’s something that one can use to make a living with. Maybe it’s something that you love to do, especially since as Steve Redgrave points out, ‘the better that you find you do something, the more you enjoy it, and the more you like doing it, the more you get success from it. It’s self-propelling in some ways.’ In the case of most Olympians, including me, it is a combination of both.

Some people never find their inborn gifts, some find them late in life, and some, like me, are fortunate to find them early on. I was very lucky that when I was growing up we spent most of our free time in my neighbourhood playing games and sports with the other kids. That’s how I discovered that I was fast. Even then, however, had I just followed what my friends did, I would have only played football, which is like a religion in Texas. I would never have found my love for track as a sport and never would have discovered just how good I could be, which ultimately turned out to be the best in the world.

That is why I encourage my own son, and any young people I talk to, to try different things. But that’s not the national trend. Instead of competing in after-school pick-up games, most kids these days grow up playing organised sports as part of youth teams and leagues which have become big business. As a result, most of the kids who come into my sports performance training centre, Michael Johnson Performance, have already started to specialise in one sport as early as age ten, so they lack the athleticism that we kids from the seventies developed from playing multiple sports. I developed my speed from sprinting, for example. But I also developed explosive power, which helped me to be a better sprinter, from playing basketball. I developed my quickness – the ability to make short bursts of speed in different directions – from playing football.

The kids who specialise early also never get to search out what really stirs them. I want my son to play a sport, to learn to play an instrument, and to try new things, so that he can discover what he is passionate about and in what areas he is gifted. Of course everyone believes that because he is my son he must be fast, and they immediately ask about his speed and whether he’s going to be a sprinter. But the fact that he’s my son doesn’t automatically make him naturally gifted at athletics or any sport. And it certainly doesn’t guarantee that he will be passionate about – or even like – athletics or sports. I understand that, so the last thing I would do is push him to participate in athletics or try to become an Olympic athlete. It is his life, and it’s up to him to decide what he wants to do with it and to discover what he enjoys and what talent he is blessed with.

At this point in his life (he’s 11) I do mandate that he participate in some sport, since I know that there are incredible lessons to be learned from taking part in sports. But I give him the right to choose which sport. If he decides to get serious, I’ll make sure he has the coaching support that he needs. But we won’t be talking about the Olympics or any other top-level competition right off the bat.

Unfortunately, too many parents and/or coaches these days do exactly that, telling students that they can aspire to the Olympics or the NBA or the Premier League the moment they show any promise. As a result kids are aiming for the Olympics or professional sports before they’ve even won their school’s championship.

NOT SO FAST

Even those high school athletes who are highly sought after by the Colleges start getting ahead of themselves. Right away they start thinking Olympics, they start thinking professional career, they start thinking endorsement contracts and deals. There’s a danger to that, which we’ll explore at length in Chapter 4. Conversely, focusing on how to improve performance instead of where that performance might lead seems to contribute to the kind of success that builds Olympic champions.

As a teenage competitor, I just wanted to be the fastest 16-year-old in Dallas. To my benefit, I didn’t think beyond that. I’m far from being the only Olympic late bloomer. For many Olympic champions the notion of even participating in – let alone winning – the Olympics took a while to set in.

‘I think I ought to say something to you,’ Sebastian Coe’s father and coach Peter said to his son on a rain-soaked night in the late 1970s as they walked off the training field. The middle-distance runner readied himself to hear a message about the training session he had just completed or his upcoming race. Instead, his father said, ‘I think you’re going to go to the Olympic Games. I’ve watched people get to Olympic Games and not deal with it that well, and I’ll just guess maybe it’s something we ought to start thinking about.’ Seb just smiled. Although the notion seemed too improbable to take seriously at the time, he would go on to set eight outdoor and three indoor world records in middle-distance track events and win four Olympic medals, including the 1500 metres gold medal at the Olympic Games in 1980 and 1984.

Even though I didn’t see myself as an Olympian at first, I always thought I would do something special. Although my family didn’t have a lot when I was growing up, I figured I would be successful. I assumed, however, that my dream of controlling my own situation, having the things I wanted and travelling would come from having my own business. I had no dream of being a professional athlete. And since I spent most of my time playing outside rather than watching a lot of television, I really knew nothing about the Olympics.

Until well into high school, sport was just something I did for fun. Sure I liked being the fastest. But there was no strategy involved. I just went out to competitions and started running when the gun went off. Then in my final year of high school, as the best on my high school team, people started to talk about my potential to be district champion, regional champion, or maybe even state champion. The biggest prize for a high school athlete is being a state champion. In order to compete to be a state champion you have to finish in the top two in your district. Then you advance to your region and must finish in the top two in the regional competition. I lived and competed in the hardest district in the country, so just advancing out of district was extremely difficult. There would be kids that I was a lot faster than who would get to state because they came from an area where there weren’t many fast athletes. I had to learn how to compete when you are up against athletes who are similarly or equally talented.

This was the first time I started to have to think about how I was going to beat other athletes. How was I going to run faster than them? I had to learn to prepare to compete against them. If a racer was in front of me and I had to go get him, what should I do? Did I just try harder? Did I need to be patient?

You need to think about those things before the race starts. In addition, because you know the athletes you’re up against, you know what they’re capable of, it makes you nervous. How do you deal with that? And how do you deal with the expectations and the pressure and still deliver your best performance? When you put all of that together, what you’re doing is learning to compete.

I would have to wait a few years for that. By the time I was 13 I was already faster than everyone on my school track team, but in competitions against other schools I would win some races and lose some races. I won more than I lost, but when I lost I was disappointed because I didn’t like the feeling of losing any more as a young teenager than I had as a youth. I don’t know what it was that I didn’t like about losing other than the fact that if I was losing, then I wasn’t winning, and I liked winning.

At that point in my life I didn’t know what to do about losing except to work harder at whatever drill my coach was giving me during practice each day, and to try harder in the races. This seemed to help somewhat but still didn’t guarantee me victory every time.

What I know now, as an owner of a performance training company training youth athletes between the ages of 9 and 18, is that it’s between 12 and 15 that most kids will make a major leap in their natural athletic ability. Some will develop faster than others. I remember that one of the kids I beat the first time I raced him proceeded to beat me every other time we raced. I don’t know what his real name was, but he went by the name Tank. As his name might indicate, he was bigger than me. I remember that he had very thick legs and already had a moustache. Knowing what I know now, I would say that Tank was probably a bit ahead of me in his development.

I took two years away from sport from the age of 14 when I first started high school. My school was a special career development school that only accepted the best of the kids who applied, and each student chose a career focus from many different offerings. At the time I dreamed of becoming an architect, so I spent half of the day learning about that particular career. Eventually I missed sport and came back to track.

When I started competing again at the age of 16, having not played any sports for two years, I had made a big leap in my athletics development, in large measure because I had matured physically. I was immediately winning races easily and working hard which had become standard procedure for me. But I still wasn’t winning every race and I still hated that. In my third year of high school I had won every race until the district championship which I lost, finishing third, and it ended my season. Roy Martin and Gary Henry, who were older than me by one year and in their final years of high school and also very good athletes, had both finished ahead of me.

GOOD COACHING HELPS

The more I thought about why I had lost, the more I put together different things I had heard from other people about the impact that good track coaches who trained their athletes all year could make. My coach, Joel Ezar, was a wonderful man with whom I had a great relationship. But he was not a great track coach; he was a football coach who coached track in the spring when the football season was over. So I simply wasn’t as ready as those other athletes I was losing to. In addition, they knew more about what they were doing on the track than I did.

I didn’t know what to do about the coaching gap, but believed that I could solve it by working harder. The next year, my final year of high school, two other athletes/friends and I began to go out on our own after school and run. We didn’t really know what we were doing but we didn’t know that. We just felt that if we worked in the autumn instead of doing nothing we would be better in the spring.

I hadn’t yet developed my absolute hatred for losing (rather than mere dislike of it). Even so, I was always looking for a way to prevent myself from losing. Throughout my life, as I matured and moved from one level of training and competing to the next, it became clearer exactly what I needed to do to be the best I could be. I just always believed that if I was the best I could be, I wouldn’t lose.

I’ve always said, and I always tell athletes, that if you run your best race and you lose, you have nothing to be ashamed of or disappointed in. I still believe that. But I, personally, never had a loss where I felt it was my best race. Even when I competed to my best ability in high school and lost, I didn’t feel it was my best race because I didn’t feel I was as prepared from a training standpoint as I could have been. A big part of my decision when I was deciding which university to compete for was which coach would be able to help me achieve my best.

In spite of not having a real track coach during my high school career, I still managed to win both the district and regional championships. At the state championship I finished second in the 200 metres behind Derrick Florence, who still holds the high school record for 100 metres and to whom I would never lose again. I wasn’t happy about not winning, but I was more excited that I would be competing at college than I was disappointed that I had lost the state championship.

Originally I viewed the track scholarship I’d accepted from Baylor University only as a means to go to a better college than I would if I had to pay for it myself. But in 1986, between high school and college, I finally start thinking about professional track. I was working in an office that summer, when I started seeing newspaper headlines about the US Olympic Sports Festival in Houston. Reading about Carl Lewis, Calvin Smith and Floyd Heard arriving in Houston to compete in this high-level competition triggered my initial aspirations to run and compete professionally. After finishing the article I found myself for the first time daydreaming about competing against the best in the world and envisioning myself being at this competition with these athletes. I started to really believe that I could be great, because I knew that I hadn’t reached my full potential in high school.

At Baylor University I was in a serious training programme for the first time. It was tough in the beginning. I hated the weight workouts, which I avoided. But I loved training on the track each day and looked forward to it. I approached each day like a competition because I could feel myself getting stronger and better.

AIMING HIGH, HIGHER, HIGHEST

Even though I made some great strides during my first year, I got injured at the end of the season and wasn’t able to compete in the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) university championships. So the following year I focused on becoming an NCAA champion. I hadn’t even considered higher-level competition – let alone the Olympics – until one of my team-mates, Raymond Pierre, went on to compete in the US national championships after the college national championships. Raymond did really well at the US championships, finishing fourth in the 400 metres. This earned him a position on the US national team for the 1987 World Championships, which would be held later in the summer in Rome. Raymond spent most of the summer in Europe competing on the international circuit and once competed as an alternate for the US team, running in the preliminary round of the 4 x 400 metres relay team that won the gold medal.

The day he returned from Rome, school had already started and the team had already started training. Raymond came out to the track wearing a USA team uniform shirt. The only way to get your hands on any official USA track team gear was to make a US team, which was a great accomplishment, so having the gear was a badge of honour. I had seen in my freshman year a handful of athletes from other universities who had competed on US teams wearing USA team gear, and I wanted that. It seemed really cool, because it showed the accomplishment, and signified how good the athlete was.

Raymond was an athlete whom I knew well and who had become a friend. He was the only person I knew personally who had actually competed on a US national team and on the professional international circuit. After practice he invited me over to his apartment. When I got there he was still unpacking his bags. He had become a Nike-supported athlete, which meant that since he wasn’t a professional athlete yet they couldn’t pay him but they could send him all the shoes and gear he wanted. He had bags of new Nike gear and USA team gear. He had picked up gifts that were given to him at the international competitions he had taken part in. There were CD players too, which in 1987 was a new technology and a very cool thing to have.

My eyes opened as wide as the Olympic medals I would eventually earn. I couldn’t believe all of the free gear and gifts he had received. And he had actually had the experience of competing on a US team and the international circuit, which he told me all about. I wanted that experience myself. To top all of that off, a week later Raymond drove up to practise in a really cool new red scooter. Those had become really popular in the US then, and he had been able to buy it with the expense money he received from his trip to Europe. I was hooked and needless to say inspired. I asked Raymond questions for weeks after his return, and he was happy to share every detail of his trip and experience with me.

Unlike me, some Olympian champions caught Olympic fever early on. ‘That’s what I want to do in life,’ Sally Gunnell realised at the age of 14 as she sat glued to the television during the Moscow Olympics watching anything that moved. Entranced with Nadia Comaneci and Olga Korbut, she decided to join a gymnastic club. Only after another girl at her school announced that she was going down to athletics did Sally decide to go along. ‘I thought it would be better to go with somebody rather than go on my own,’ she recalls. So she joined the athletics club and went on to win a gold medal in the 400 metres hurdles at the 1992 Olympics.

Steve Redgrave found success so early in his rowing career that he simply assumed winning the Olympics was inevitable. ‘The first year, we thought we were brilliant,’ he says. After just messing around in the water, the team had entered their first race for fun and actually won. The following season they entered seven events and won all seven. ‘We were God’s gift to rowing,’ he said. By the time Steve was 15 people had begun to tell him, ‘You’re really good at this. One day you could be a world champion.’

‘I thought, “World champion sounds nice; why not Olympic champion?” I knew I wanted to be an Olympian, because I was the best in the country. Why not?’

That sense of inevitability would prove to be both his great motivation and, initially, his downfall. ‘I figured, “All I’ve got to do is follow what the coaches are telling me to do and it will happen,”’ he recalls. ‘It wasn’t until 1983 when I went to the senior world championships as a single sculler and I got eliminated – I didn’t make the top 12 – that I suddenly thought, “I am good domestically, I’m okay internationally, but not the same sort of level as people are saying I am good at.” Suddenly it dawned on me that if you have an ability you’ve got to bring that ability out. It’s about how hard and how well you prepare. That was the turning point in my career.’ It would also prove to be the turning point in his life, transforming him from ‘shy goose’ to confident five-time gold medallist.