По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

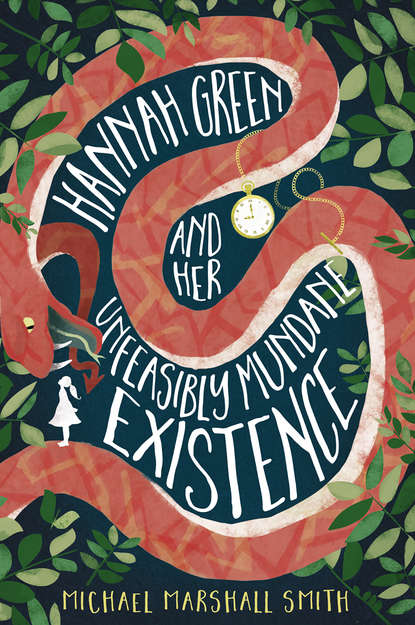

Hannah Green and Her Unfeasibly Mundane Existence

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Hannah also saw her Aunt Zo, who came down a few times to keep her company. Zoë was twenty-eight. She lived in the city and was an artist-or-something. She had alarmingly spiky dyed-blond hair and several tattoos and wore black most of the time and was her dad’s much younger sister, though it seemed to Hannah that Zo and her dad always looked at each other with cautious bemusement, as if they weren’t sure they belonged to the same species, never mind family. Hannah didn’t know what an ‘artist-or-something’ even was. She’d intuited it might not be an entirely complimentary term because it was how her mother described Zoë, and Hannah’s mom and Zo had not always appeared to get on super-well. It had to be different to an ‘artist’, certainly, because extensive tests had demonstrated that Aunt Zo couldn’t draw at all.

She was friendly, though, and fun, and had gone to a lot of trouble to explain that the fact Hannah’s parents didn’t live together right now didn’t mean either of them loved her any less. Sometimes people lived together forever, and sometimes they did not. That was between them, and the reasons could be impossible for anybody else to understand. Sometimes it was because of something big or weird and unfixable. Sometimes it was merely something ‘mundane’.

Hannah hadn’t understood what this word meant. Aunt Zo waved her hands vaguely, and said, ‘Well, you know. Mundane.’

Later Hannah looked it up on the internet. The internet said that the word came from the Latin mundus, meaning ‘world’, and thus referred to things ‘of the earthly world, rather than a heavenly or spiritual one’. That made zero sense until she realized this was only a second thing it could mean, and that usually people used it to mean ‘dull, lacking interest or excitement’.

Hannah nodded at this. She didn’t see how Mom and Dad not living together could be without interest, but she was beginning to feel her life in general most certainly could.

The next time she saw Zo was when her aunt came to babysit overnight because Hannah’s dad had to fly down to a meeting in Los Angeles. Hannah dropped the word into conversation, and was pleased to see her aunt smile to herself. Emboldened, Hannah tentatively asked whether maybe, next time, rather than Zo coming to Santa Cruz, Hannah could come up to the city instead. She did not say, but felt, they could be girls together there, and have new and unusual fun that would not be dull or lack excitement. Zo said yes, maybe, and how about they made some more popcorn and watched a movie.

Hannah was old and smart enough to understand that whatever ‘mundane’ might mean, ‘maybe’ generally meant ‘no’.

Otherwise, life dragged on like a really long television show that was impossible to turn off. She went to school and ate and slept. Mom sent her an email every couple of days, and they spoke on Skype once a week. The emails were short, and usually about the weather in London, England, where she was working. The phone conversations were better, though it sometimes felt as though the actress playing her mother had changed.

Hannah realized it wasn’t likely that, even when (or if) her mom did come back, she was going to come and live with Hannah and her dad. Straight away, anyway. Missing her mother was tough, but bearable. Hannah put thoughts of her in a box in her head and closed it up (not too tightly, just enough to stop it popping open all the time and making her cry) and told herself that she was welcome to look inside however often she liked. In her imagination the box was ornate and intricate and golden, like something out of a storybook.

Missing her dad was worse, because he was right there.

He hadn’t gone away, but he had. Virtually everything about him with the exception of his appearance (though he often looked tired, and didn’t smile with his eyes) had changed. He hugged her at bedtime. He hugged her at the school gate. When something needed to be said, one of them said it, and the other listened. But sometimes when Hannah came into a room without him realizing, she would look at him for a while and it was as though there was nobody there.

Otherwise, nothing much changed.

School.

Homework.

Food.

Bed.

School.

Homework.

Food.

Bed …

… like waves lapping on a deserted shore. Life was flat and grey and quiet, all the more so because every other adult with whom she came into contact – teachers at school, her friends’ moms and dads, even the instructor at gym, who’d always been snarky with literally everyone – treated her differently now. They were polite and accommodating and they always smiled and seemed to look at her more directly than before. They were so very nice to her, in fact, that the world no longer had edge or bite. It lost all shape and colour and momentum, and any sense of light or shade. It was like living in a cloud.

Late one autumnal afternoon, as she sat watching through the window as a squirrel played in the tree outside, looking so in charge of its life, having so much fun, Hannah realized that her own life had become ‘mundane’.

Horribly, unfeasibly mundane.

So I suppose that’s where we’ll begin.

Don’t worry, things will start to happen. This hasn’t been the actual story yet. It’s background, a few moments spent sifting through the tales already in progress in order to pick a moment in time and say: ‘So now let’s see what happened next.’

And we will.

But before we get any further into Hannah’s story, we need to go and meet someone else.

Chapter 2 (#u4abea521-3a00-5603-8c27-f00fe3489f30)

Because, meanwhile, an old man was dozing on the terrace of the Palace Hotel, on Miami’s South Beach.

The hotel stands amidst a half-mile of art deco jewels restored to their former glory in the 1980s, and – like many of the others – was determinedly now running back to seed, as though that was the state in which it felt most comfortable. The old man had a local newspaper on his lap but he had not read it. To one side, on the table supporting the umbrella protecting him from the sun, was a glass of ice tea that had long ago come up to ambient temperature. A large bug was swimming in it, a leisurely freestyle. The waiter working the terrace had approached the table several times to see if the gaunt old buzzard wanted his glass refreshed. Each time he’d discovered the man’s eyes were closed. His position had not changed in quite a while.

Nonetheless the waiter decided to try one more time. In half an hour his shift would be over. In most ways that was awesome. The afternoon had been hellishly humid and the waiter was looking forward to returning to his ratty apartment, taking a shower, sitting out on his balcony and smoking pot for a couple of hours before hitting the town in the hope of finding some margarita-addled divorcée or, failing that, simply getting wasted. Business on the terrace had not been brisk, however. He was below quota on tips (and behind on his rent), and that was why he decided – now it was approaching five – it was worth one final attempt to upsell the old dude in the crumpled suit into a big glass of wine or, better still, an overpriced cocktail.

He went and stood over him.

The old man’s head was tilted forwards in sleep, showcasing a pale forehead dotted with liver spots, a sizable beak of a nose, and combed-back hair that, though pure white, remained in decent supply. Large, mottled hands rested on knees that appeared bony even through the black linen of his suit. Who wore black in Florida, for God’s sake?

The waiter coughed. There was no response.

He coughed again, more loudly.

Consciousness returned slowly.

It felt as though it was coming from a great distance, and that was because this was not a normal awakening. It wasn’t merely a matter of rising from sleep. On this day, the old man woke from a far deeper slumber.

He opened his eyes and for a moment he had no idea where he was. It was hot. It was bright, though the quality of the light suggested it must be towards the end of the afternoon. He could see the glint of some ocean or other, past the stone terrace on which he sat.

And there was a young man, wearing a white apron, standing in front of him and smiling the kind of smile that always had financial outlay attached to it.

‘Refreshed, sir?’

The old man stared confusedly at him for a moment, and then sat up straight. He peered around the terrace and saw young couples at other tables, and a few older people wearing hats and looking out at the ocean as if waiting for it to do something. Hotels on either side. Palm trees.

He turned back to the waiter. ‘Where am I?’

The waiter sighed. The old fart had seemed fine when he ordered his ice tea earlier. Evidently a day in the sun had fried what was left of his wits.

‘Wondered if I could interest you in a cold glass of Chardonnay, sir? We have an intriguing selection. Though perhaps a crisp Sauvignon Blanc would be more to your taste? Or a Martini, a Bellini, or a Sobotini? That’s the signature creation of our in-house executive mixologist, Ralph Sobo, and features a trio of—’

‘Did I ask you to recite the entire drinks menu?’

‘No, sir.’

‘So?’

The waiter smiled tightly. ‘You are on the terrace of the Palace Hotel,’ he said, offensively slowly. ‘South Beach. Miami. The United States of America.’ He leaned forwards and added, loudly enough for people nearby to turn and smile to themselves, ‘Planet Earth.’

The man frowned. ‘How long have I been here?’

‘In this spot? The entire afternoon. The hotel? I have no clue. I’m sure reception can assist you with that information, along with your name, if that’s also slipped your mind. Now – can I help you with a beverage, or not?’