По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

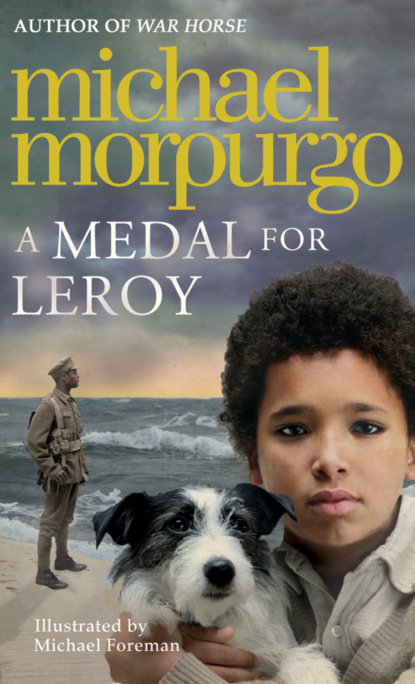

A Medal for Leroy

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

So that was why, from then on, I always kept Papa’s silver medal on my mantelpiece alongside all my football cups and shields. I’d look at it often, touch it for luck sometimes when I was going off to play a football match, or before a spelling test at school. Occasionally, in the secrecy of my bedroom, I’d pin it on, look at myself in the mirror, and wonder if I could ever have been as brave as he was. I discovered later, after more pestering, that it wasn’t the only medal for bravery Papa had won.

Maman revealed to me one morning as we were driving down to Folkestone for our New Year visit to the Aunties – Auntie Pish and Auntie Snowdrop, as we called them – that Auntie Snowdrop had Papa’s other medals.

“She’ll show you, I expect,” she said, “if you ask. She’s very proud of them.”

I knew they had a photo of Papa in his RAF uniform. It was in a silver frame on the mantelpiece in their sitting room, always polished up and gleaming. He looked serious, frowning slightly as if some shadow was hanging over him. There were scarlet poppies lying scattered around the photograph. It was like a shrine, I thought. Auntie Pish was the loud one, talkative and bossy, forever telling me I should be tidier, and blaming Maman for it. She would chuck me under the chin and arrange my collar and tie – we always dressed up in our best for these visits – and she’d tell me, her voice catching, how alike we were, my Papa and I.

I’d often stand in front of that photo and try to see myself in my Papa’s face. He had a moustache and high cheekbones, deep-set eyes, and in the photo his skin looked darker than mine too. Maman had told me that his hair was frizzy like mine. But most of his hair was hidden under his cap. In his RAF uniform with his cap perched on his head, he was simply a hero to me, a Spitfire pilot, like a god almost, not like me at all.

I dreaded these visits, and I could tell, even though she didn’t ever say it, that Maman did too. For me though there was always Jasper to look forward to. He was their little white Jack Russell terrier with black eyes, bouncy and yappy and funny. I loved him, and he loved me. Every time we left I wanted to take him with us. On the journey home I’d go on and on about having a Jasper of our own, but Maman wouldn’t hear of it. “Dogs!” she’d say. “They make a mess, they smell, they have fleas which is why they scratch. And they lick themselves all over in public. Répugnant! Abhorrent! Dégoûtant!” (She knew a lot of French words for disgusting!) “And they bite. Why would I want a dog? Why would anyone want a dog?”

I remember this visit better than any of the others, maybe because of the medals, or maybe because it was the last. As we drove towards Folkestone, Maman’s nerves, as usual, were getting the better of her. I could tell because she was grinding the gears and cursing the car, in French, a sure sign with her. She was becoming more preoccupied with every mile. She was smoking one cigarette after another – she always smoked frantically when she was anxious. She started telling me what I must and must not say, how I must behave. She was never like this at home, only on our way to Folkestone to see the Aunties.

Once we arrived outside their bungalow she spent long minutes putting on her makeup and powdering her nose. When she finished she clicked her powder compact shut and turned to me with a sigh, a smile of resignation on her face. “Well, how do I look?” she asked, cheerier now. “Armour on, brave face on. ‘Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more’ – that’s from Shakespeare, Henry the Fifth – your Papa said that when we visited them together that first time, and every time afterwards too. It’s what I have to remember, Michael. The Aunties may not be easy, but they adored your Papa. He was the centre of their lives, just as he was for me too. We are all the family they have now, now that he’s gone. We mustn’t forget that. I don’t think they ever got over your Papa’s death, you know. So they and I, we have that in common too. We miss him every day of our lives.”

Maman had never spoken about Papa to me like this before, never once talked about her feelings until that moment. I think she might have said more, but then we saw Auntie Snowdrop come scurrying down the path and out of the front gate, waving to us, Jasper running on ahead of her, yapping at the gulls in the garden, scattering them to the wind. “Oh God, that dog,” Maman whispered under her breath. “And those horrible elves are still there in the front garden.”

“Garden gnomes, Maman,” I said. “They’re garden gnomes, and I like them, specially the one that’s fishing. And I like Jasper, too.” I was opening the car door by now. “It’s the rock cakes I don’t like. The currants are as hard as nails.”

“Won’t you have another rock cake, Michael dear?” Maman said, imitating Auntie Pish’s high-pitched tremulous voice and very proper English accent. “There’s plenty left, you know. And mind your crumbs. Pish, you’re getting them all over the carpet.”

We got out of the car still laughing, as Jasper came scuttling along the pavement towards us, Auntie Snowdrop close behind him, her eyes full of welcoming tears. For her sake I made myself look as happy as I could to see her again too – and with Auntie Snowdrop, to be honest, that was not at all difficult. A bit ‘doolally’ she may have been, ‘away with the fairies’ – that was how Auntie Pish often described her – but she was always loving towards Maman and me, thoughtful and kind. To meet Auntie Pish though, I always had to steel myself, and I could see Maman did too. She was standing there now at the front door waiting for us as we came up the path. I bowed my head to avoid the bristly kiss.

“Pish, we thought you’d be here an hour ago,” she said. “What kept you?” We were usually met with a reprimand of one kind or another. “Well, you’re here now, I suppose,” she went on. “Better late than never. You’d better come along in. Just in time for elevenses. The rock cakes are waiting.” She tightened my tie and arranged my collar. “That’s better, Michael dear. Still not the tidiest of boys, are we? I made the rock cakes specially, you know. Plenty to go round.” Then she shouted to Auntie Snowdrop, “Martha, do make sure you shut that gate properly, won’t you! Pish, she’s always leaving it open. She’s so forgetful these days. Come along!”

Maman didn’t dare look at me and I didn’t dare look at her.

(#ulink_9e804d28-7b4b-543e-99ae-f956f2bc8cec)

me like his best friend. He sat by my feet under the kitchen table, and surreptitiously ate all the rock cakes I gave him. He chewed away secretly, though sometimes a little too noisily, on the currants, licked his lips, then waited for more, his eyes wide with hope and expectation.

The chatter round the table echoed the last visit, and the one before, and the one before, as it always did. Auntie Pish did most of the talking, of course, and loudly because she was a bit deaf, peppering Maman and me with questions about my progress at school. She wanted only the good news – we knew that – so that’s what we told her: winning a prize for effort, singing a solo in the carol service again, being top scorer in the football team.

She interrupted her interrogation from time to time with critical observations about my upbringing. “He’s still not very big, is he?” she said to Maman. “Pish. I still don’t think you feed him enough, you know. That’s what we think, isn’t it, Martha?”

It always came as something of a surprise to me when she called Auntie Snowdrop by her proper name. I had to think twice. Their names were too alike anyway, Martha and Mary. Perhaps that was why Maman and I had given them nicknames in the first place. “We shall need more milk from the larder, Martha,” she went on, and then much louder, “I said, we want more milk, Martha.” Auntie Pish’s solution to her own deafness was to presume everyone else was deaf too.

Auntie Snowdrop was looking down at me adoringly, clearly not paying any attention to her elder sister. In all the years we’d visited, Auntie Snowdrop had said very little to me or to anyone – she let her sister do all the talking for both of them. But she’d always sit beside me, often with her arm around me, laying her hand gently on my hair from time to time. I think she just loved to touch it.

“Martha! The milk!”

Auntie Snowdrop got up and scuttled away apologetically. Auntie Pish reached out and chucked me under the chin, shaking her head sadly. “So like your father you are,” she said. “Bigger ears though. His ears didn’t stick out so much.” But her mind was soon on other things. “And don’t go helping yourself to my prune juice again,” she called out after Auntie Snowdrop. Then confidentially to us, “She does you know. Pish, Martha’s an awful thief when it comes to my prune juice. I have to keep my eye on these things. I have to keep my eye on everything.”

Maman and I had worked out over the years how not to look at one another whenever prune juice or rock cakes were mentioned. The giggles would well up inside of us, threatening to break out. It helped that I was a little bit frightened of Auntie Pish – Maman was wary too, I think. Auntie Pish could be cruel, with Auntie Snowdrop in particular. Maman and I both disliked the way she treated Auntie Snowdrop, putting her down all the time. We hated especially how she’d talk about her behind her back.

In the sitting room after ‘elevenses’, as the Aunties always called the mid-morning break for tea and rock cakes, Auntie Pish would preside grandly in her armchair by the fire in her voluminous dress – she was a big woman anyway and always wore dresses that seemed to overflow in every direction. She’d hold court while Auntie Snowdrop made the lunch out in the kitchen. Auntie Snowdrop would be humming away as she worked, tunes I often recognised, because they were songs she’d taught me too: ‘Down by the Sally Gardens’, maybe – which was my favourite – or ‘Danny Boy’, or ‘Speed Bonny Boat’. She was always humming or singing something. She had a very tuneful voice, sweet and soft and light, a voice that suited her.

Lunch was always the same on our visits: corned beef and bubble and squeak. And for pudding we had custard with brown sugar, because years before, when I was about three, Maman had told Auntie Snowdrop this was my favourite meal. Over lunch Auntie Snowdrop would fuss over me like a mother hen, making sure I had enough. The trouble was that I had very quickly had quite enough. At nine years old, I no longer liked corned beef and bubble and squeak, and I had gone off custard years ago. I hated the stuff, but I’d never had the nerve to tell her, and nor had Maman.

That lunchtime I had to work my way through three helpings of custard. Swallowing the last few spoonfuls was hard, so hard. I knew I mustn’t leave anything in my bowl, that it must be scraped clean, that it would upset Auntie Snowdrop if it wasn’t, and also invoke the wrath of Auntie Pish, whose favourite mantra at meal times was always, ‘Waste not, want not’.

After lunch we went down to the beach as usual, and as usual Auntie Snowdrop took a bunch of snowdrops with her, snowdrops I’d helped pick with her from the garden – they grew in a great white carpet all around the garden gnomes. Jasper hated gulls, all gulls. He chased them fruitlessly up and down the beach, yapping at every one of them, returning to us exhausted but happy, and still yapping. We tramped together along the beach until Auntie Pish decided she had found just the right place. She waved her walking stick imperiously out to sea. “This’ll do, Martha,” she said. “Get on with it then.”

Every year until now Auntie Snowdrop had performed the ceremony herself, but this time she turned to me. “I think maybe Michael should do it,” she said, and she handed me the flowers. “He’s old enough, don’t you think? And after all, he was your father. Would you like to do it, Michael?”

Auntie Pish was clearly surprised, as we were, at how Auntie Snowdrop had suddenly taken the initiative, and she didn’t like it one bit. She waved her stick at me impatiently. “Very well,” she snapped. “If you’re going to do it, then get on with it. But look out for the waves. Don’t go getting your feet wet, Michael.”

I took the flowers from Auntie Snowdrop and walked down to the water’s edge. I did it just as she had done it every year I could remember. I reached out and dropped the snowdrops into the sea one by one. Some the waves took away, others were washed at once back up onto the beach, and left stranded round my feet.

I felt Maman beside me, her arm around my shoulder. “Your Papa adored snowdrops, you know,” she whispered.

“Is he really out there, Maman?” I asked her then. “Is that where his Spitfire went down?”

“Somewhere in the Channel, chéri,” she replied. “No one quite knows where. But it doesn’t matter, does it? He’s with us always.”

We turned back then and walked up the beach towards the Aunties.

Auntie Snowdrop had her handkerchief to her mouth. I could see she was crying quietly.

“Time for tea,” Auntie Pish said. “Martha, would you please stop that dog yapping? He’s driving me mad. Come along. And do keep up, Martha, don’t drag along behind so much. Pish!” And she strode off up the beach, stabbing her stick into the pebbles as she went. “Come along, come along.”

Auntie Snowdrop caught my eye, smiled and raised her eyebrows, enduring the moment. She was telling me in her own silent way, don’t worry. I’m used to it. I smiled back in solidarity.

The walk home took a while, a bit longer than usual. That was when I noticed Auntie Snowdrop was wheezing a bit, that she had to stop from time to time to catch her breath, so much so that in the end I left Jasper to run on ahead, and went back to keep her company. She smiled her thanks at me and took my hand in hers. She held on to me to steady herself, I remember that. And her hand was so cold.

(#ulink_d254285d-b1d2-59b8-8d5d-25f2a8f2314d)

I couldn’t wait to be gone. They clinked their teaspoons on their cups and talked, and talked, and went on talking, on and on, about what I neither knew nor cared. Auntie Pish was doing most of the talking and Maman looked about as fed up as I felt. I kept looking up at the photo of Papa on the mantelpiece, at the poppies all around it. Maman was twiddling her ring, something she often did, particularly when she was with the Aunties. That was when I remembered the medal I had found in the box when we’d moved house a few weeks before.

Maman must have guessed my thoughts, or read them perhaps. Suddenly she put her hand on mine, and interrupted Auntie Pish, who was not used to being interrupted.

“Sorry, Auntie Mary, but I’ve just remembered…” she began. Auntie Pish did not look at all pleased. “Auntie Martha. Roy’s medals – the ones I let you have, remember? He’s got one of his own at home, haven’t you, chéri? But I know he’d love to see the others sometime. Do you mind?”

“Of course I don’t. They’re upstairs,” Auntie Snowdrop replied. “I’ll fetch them at once, shall I?”

“Yes, Martha,” Auntie Pish said, “you go and fetch them. And while you’re about it, bring us the last of the rock cakes from the kitchen, will you? I see we have empty plates. Don’t be long.”

Auntie Snowdrop folded her napkin neatly, got up and went out. Auntie Pish shook her head. “She’s always polishing those medals,” she grumbled. “I don’t know why she bothers – it only makes her sad. She still gets so upset and depressed: won’t get up in the morning, won’t eat her food, hardly speaks to me for days on end. If it wasn’t for choir practice I sometimes think she’d give up the ghost altogether. I mean, Roy died over nine years ago now. The war was a long time ago. We have to put it all behind us, that’s what I keep trying to tell her. It’s water under the bridge, I tell her. Well I mean, there’s no need for any more sadness, is there? No point. What’s done is done. You can’t bring him back, can you?”

Maman looked long at Auntie Pish before she spoke. Then she said very quietly: “Happiness, I think, is like Humpty Dumpty in that poem I used to read to Michael. ‘All the King’s horses, and all the King’s men, couldn’t put Humpty together again…’ Once it is broken, you can’t just put happiness together again. It is not possible.”

Auntie Pish didn’t know what to say, and for a change she said nothing. She cleared her throat and drank some more tea. Auntie Pish silenced. It was a rare and wonderful moment. It cheered me up no end. I almost felt like clapping, but then we heard Auntie Snowdrop coming slowly back downstairs. She came into the sitting room, carrying a wooden pencil box, holding it out in front of her, with the greatest of care, in both hands. Her eyes never left it as she put it down on the coffee table.

“Well, open it then, Martha,” Auntie Pish told her impatiently. “It won’t bite.” Auntie Snowdrop slid back the lid and took it off. There were three medals lying there on cotton wool, the King’s face looking up at me from each one.

“You see how shiny I keep them?” Auntie Snowdrop was touching them with her fingertips. “Your Papa, I always thought he looked a bit like the King – except for the moustache, of course. I never liked his moustache. He said it made him look older, more like a proper fighter pilot. I never wanted him to go to war, you know. I told him. But he wouldn’t listen to his old Auntie. This was his pencil case when he was a boy. He had it all through his school days.” Then she looked up at me and fixed me with a gaze of such intensity that I’ve never forgotten it. “You’ll never go to war, will you, Michael?” she said.

“No, Auntie,” I told her, because that’s what I knew she wanted me to say.