По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

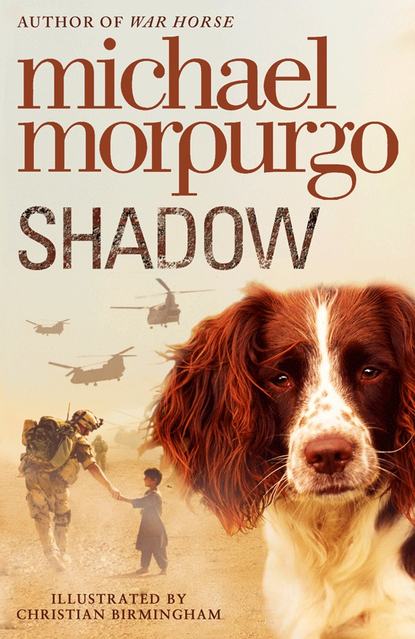

Shadow

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“In future,” she told me, “everything has to be passed by Security. Everything.”

I just nodded, buttoning my lip till she was gone. I hated myself for doing it, for not arguing back. But I knew that to have a stand-up row with her would be pointless – if I wanted Aman to see the photo. I waited till she’d gone away, winked triumphantly at Aman, slid the photo across the table, and then began pointing out who everyone was. “That’s the family in the garden, last summer. There’s the apple tree. And Matt, kneeling down beside Dog. Yes, I know. Not a very imaginative name for a dog, is it? I think he must be about the same age as Matt, same age as you. That’s pretty old for a dog.”

A sudden frown came over Aman’s face. He picked up the photo to look at it more closely. “Shadow,” he murmured, and I saw his eyes were filling with tears. “Shadow.”

“I’m sorry?” I said, not understanding at all. “Is it something in the photo?”

Without any warning, Aman got up and rushed out of the room. His mother went after him at once, leaving me sitting there and feeling rather stupid. I looked down at the photo, still trying to work out what there could possibly be in this family snap that had upset him so much.

That was when another officer came wandering over and spoke to me, in a low and overly confiding tone. “Temperamental, you see,” he said. “That’s the trouble with them. And I’m warning you, that one can be a bit surly too.”

I felt like getting up and shaking him. I should have given him a piece of my mind. I should have said, “And how would you feel being caged up in here like this? He’s just a kid, with no home, no hope, nothing to look forward to, except deportation.”

Instead, and for the second time that day, I said nothing. In keeping silent as I had, I felt I had betrayed Aman yet again. Whatever way I looked at it, the whole thing had all been my fault. I should never have shown Aman the photo.

He was just beginning to trust me, and I’d blown it. I didn’t understand why, but that didn’t make me feel any better about it. People were looking at me from all around the room. I was sure they thought I had upset Aman intentionally somehow. I waited for a while, hoping he might come back, but longing at the same time to get out of there. When he didn’t reappear, I decided to pack up the Monopoly game as quickly as I could, and go.

I had just collected up the last of the Monopoly money and was closing the lid, when I saw Aman coming back across the room towards me. He sat down opposite me again, without speaking a word, without even looking at me. I thought I’d better say something.

“I can leave the Monopoly game, if you like, if they’ll let me,” I said. “You can play it with your friends maybe.”

“I don’t have any friends in here,” he said, still not lifting his eyes. “All the friends I had are on the outside. I’m on the inside.” Then he did look up at me. “I’ve got a photo of my friends though. Mother says I should show you.”

He was looking around the room, making quite sure no one was looking. Then he took a piece of folded paper out of his pocket and handed it to me surreptitiously under the table. I opened it out on my knee.

It was an e-mail printout of a photo of a school football team, in a blue strip. They were all crowding around one another and laughing into the camera. Matt was standing at the back, his arms raised in the air, as if he had just scored a goal.

“That is my football team, and there is Matt. See him?” Aman said. “They sent it to me from school. And that’s my shirt.” They were holding up a bright blue football shirt. On the back was a number 7, and above it in large letters, AMAN.

“If you count the players,” he went on, “you will see there are only ten of them. There should be eleven. I’m the one that is missing. That’s Marlon, centre forward, twenty-seven goals last year, as good as Rooney, better even. And the tall one, like a giraffe – next to Matt at the back – that’s Flat Stanley, our goalie, the one grinning all over his face, and giving me the thumbs up. Can you see him?”

I could see him, right in the middle of the top row, holding up a huge banner that read, WE WANT YOU BACK.

“These are my friends,” Aman told me. “I want to go back to them, back to my school, back to my home in Manchester. It is where I belong, where Mother belongs. It is where Uncle Mir lives, where all our family lives. Mother says she is sorry, but she is very tired now, and she must lie down. But she sent me back to see you, to talk to you. When I spoke to Mother just a few moments ago, she said that she had a dream about you last night, even before she met you, and about Father, and about the cave in Bamiyan where we lived, about the soldiers too, and Shadow.”

“Shadow? What is… who is this Shadow?” I asked him.

“Shadow was our dog,” said Aman. “She was just like the dog in your photo. We called her Shadow, when she was ours. And then later she was called Polly. She had two names, because she had two lives. She was brown and white, like yours. The same droopy eyes and long ears.”

It was all too puzzling, too difficult to understand. “So Shadow,” I said, “she’s your dog, and she’s back at your home in Manchester then? Is that right?”

Aman shook his head. “No. It’s like Mother told me,” he said. “She said I should tell you everything, all about Shadow, and about Bamiyan, and about how we came to be in this place. Like I said, Mother says she had a dream about you last night, before she even met you. And in the dream, she told me you took us by the hand and led us out of here. She says she was not sure about you at first, but now she is. She says you are a good listener with a kind heart, that all good friends are good listeners. Like Matt, she said, just like Matt. Why else would you come to see us if you did not want to listen? She says you are our last chance, our last hope of going home to Manchester, of staying in England. This is why she told me I must tell you the whole story now, right from the beginning, so you will know why we have come here to England, and what has happened to us. She says that maybe you can help us, God willing. She says there is no one else who can, not now. Will you help us?”

“I will try, Aman, of course I will,” I replied. “But I don’t want to build up any false hopes. I really can’t promise anything.”

“I don’t want promises,” he said. “I just want you to listen to our story. That’s all. Will you do that?”

“I’m listening,” I told him.

Bamiyan (#ulink_40da88b0-c35f-532c-b264-f06c37ea1a49)

Aman

I think you should know about my grandfather first, because in a way he was the beginning.

I didn’t know him, but Mother often told me his stories – she still does sometimes – so, in a way, I do know him.

There was a time, so Grandfather told her, when Afghanistan was not as it is today. Bamiyan, where we lived, was a beautiful, peaceful valley. There was plenty to eat, and the different peoples did not fight one another: Pashtun, Usbek, Tagik, Hazara – my family is from the Hazara people.

Then the foreigners came, the Russians first, with their tanks and their planes, and after that there was no more peace, and soon there was no more food. My grandfather fought against them with the Mujahadin resistance fighters. But the Russian tanks came to our valley, to Bamiyan, and killed him, and many others.

All this was long before I was born.

After the Russians were driven out, Mother remembers that everyone was happy for a while. But then the Taliban fighters came in. At first everyone liked them, because they were Muslims like us. But we soon learned what they were really like. They hated us, especially Hazara people like us. They wanted us dead. If you did not agree with them, they killed you. They left us with nothing. They destroyed everything. They burnt our fields. They blew up all our homes, every one of them. They killed whoever they wanted to. There was nothing anyone could do, except hide.

That is why I was born in a cave in the cliff face above the village. I grew up in this cave, with my mother and grandmother. I wasn’t unhappy. I went to school. I had friends to play with. I knew nothing different.

Mother and Grandmother argued a lot, mostly about the same thing, about Grandmother’s jewels, which she kept hidden away, sewn into her mattress. Mother was always trying to get her to sell them, to buy food when we were hungry. And Grandmother always refused. She said we were always hungry, and that we would manage to survive somehow, God willing. She would always say that there was something more precious even than food, and she was saving her jewels for that. She would not say what this was, and that always made Mother very angry and upset. But I did not mind them arguing that much. I was used to it, I suppose.

Everyone I cared about in the world lived in these caves, a hundred or more of us, because there was nowhere else to go, because the Taliban had left us nowhere else to live. They had blown up all of Bamiyan, all of the houses, even the mosque.

And they did more than that. They blew up also the great stone statues of the Buddha that had been carved out of the cliff face thousands of years before. Mother watched them do it. She told me they were the biggest stone sculptures in the whole world, and that people from far away used to come to Bamiyan to see them because they were so famous. But there is nothing left of them now, just great piles of stones. The Taliban blew up our whole lives.

They were cruel people.

Then the Americans came with their tanks and their helicopters and their planes, and the Taliban were driven out of the valley, most of them anyway. We all thought things would be better for us from now on. Father spoke a little English, so he became an interpreter for the Americans. People kept saying there would soon be new houses for us to live in, and a new school. But nothing seemed to change. There was more food now, but never enough. So we were still hungry. In the cave Mother and Grandmother started quarrelling again.

Things were getting back to normal.

But then one night the Taliban came to our cave, and they took my father away. I was six years old. They called him a traitor, because he had helped the infidel Americans. Mother fought them, but she wasn’t strong enough. I screamed at them, but they just ignored me.

We never saw my father again. I remember him very well though. They cannot take away my memories of him. He used to show me the house down in the valley where he had lived, and we would sometimes walk the land where he used to graze his sheep, and grow his onions and his melons, and the orchard where he grew his big green apples.

Father would always let me go with him to load up the donkey with sticks for the fire. And every day we would go down to the stream to fetch the water, and carry it back up the steep hill to the cave. Sometimes he would take me into town to buy some bread, or a little meat from the butcher, if we had any money. Everyone liked him. We laughed a lot together, and he would wrestle with me and play with me.

He was a good father. He was a good man.

But the Taliban had destroyed everything, cut down the orchards, burnt the crops, took Father away. I never heard him laugh again. All we had left of him was his old donkey. I would talk to him instead sometimes. He was very sad, like me. I think maybe that donkey missed Father as much as I did.

After that there were just the three of us left in the cave, Mother, Grandmother, and me. For months after Father was taken away, Grandmother would spend her days lying on the mattress in the corner, and Mother would sit there beside her, gazing at nothing, hardly speaking. It was up to me now to find enough rice or bread to live on. I begged for it. I stole it. I had to. I fetched the water from the stream, a long walk down the hill and a long walk up, and I tried to bring in enough sticks to keep the fire going.

Somehow we managed to get through the winters without starving or freezing to death. But Grandmother’s legs were getting worse all the time. She could hardly get up at all now, unless one of us helped her.

What happened to Mother was my fault. I was with her at the market in town when I stole the apple, just one apple, nothing much – we had none left of our own by now. I was good at pinching things. I had never been spotted before. But this time I got careless. This time I got caught.

“Dirty Dog! Dirty Foreign Dog!” (#ulink_f4bfb3e2-9e44-584b-9103-40de6ebee5b5)

Aman