По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

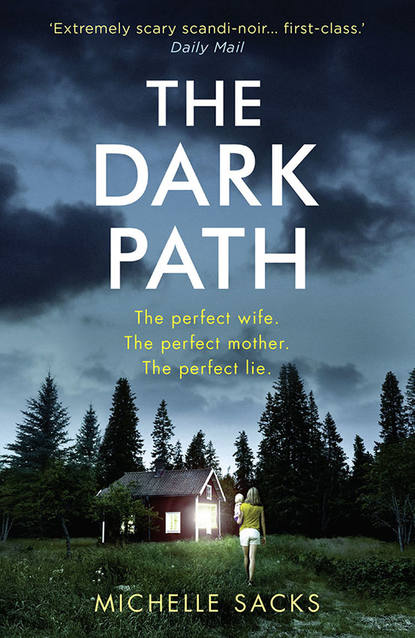

The Dark Path: The dark, shocking thriller that everyone is talking about

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

You’ll be a terrific mother, Merry, he told me all through the pregnancy, through the nausea and the discomfort and that feeling of hostile, unstoppable invasion. He couldn’t take his eyes off me, or his hands off my swollen belly. He was mesmerized with what he imagined was his singular achievement.

Look at this, he marveled. We made this life; we made this living being inside of you.

The miracle of it, he said.

It felt like the very farthest thing. But Sam had already carried us away on a dream and a plan: Sweden. A brand-new life. Shed the old skin and slip into another. There was something enticing about the idea of it, of leaving New York with its many secrets and shames. Some of them Sam’s, the biggest one belonging to me.

The baby, the baby. Sam loves him with such ferocity, it can sometimes make it hard for me to breathe. And now there will be Frank to think of. Frank in my house. Frank in my life. So close. Perhaps too close. We are childhood friends, that most dangerous kind. Bonded over memories and sleepovers and secrets; over betrayals and jealousies and cruelties big and small. She has always been in my life somehow, a lingering presence. Even when we are far apart, separated by cities or continents, it is Frank I think of most. It is Frank I crave. I imagine her reacting to what I do and say, to how I live, to whom I love. I imagine Frank taking it all in. I imagine what it feels like for her, to see my life and hold it up against her own. We need each other like this. We always have.

I remember when she first moved to New York – snapped up after her MBA by one of the top consulting firms. Suddenly she was a different Frank. Jet-setting between cities, dating hedgefund managers, living in a penthouse apartment with a Russian art dealer for a roommate. Well, I packed my things and moved there myself a few months later. My father paid my rent.

But what are you doing here? Frank asked when I arrived on her doorstep one Saturday morning with two cream cheese bagels.

I’ve always planned to live here, I said, I told you.

Yes. We need each other. Without the other, how would either of us exist?

It was nine o’clock when Sam returned home, much earlier than he’d said. The baby was in his crib, newly asleep with the help of a teaspoon or two of cough syrup. I do this occasionally, on the more difficult days. It’s meant to be harmless. Mother’s little helper, is all.

Other things I do too. Like put pillows too close to the baby’s head. Or set him down to nap just a touch too near the edge of the bed. I don’t know why. I don’t know what it is that compels me. I only know I cannot stop it. Often I weep. Other times, all is numb, whole parts of me dead and blackened like a gangrenous limb. Immune to life.

I was on the sofa when I heard Sam’s car on the gravel. I startled. I’d been watching a show about women who compete with their best friends to see who can throw the better wedding. I hadn’t yet cleaned myself up. I quickly snapped shut the laptop and opened a book on early childhood development.

Hello, wife, Sam said, kissing me on the mouth.

His breath was stale, the smell of rotting meat. My stomach turned.

How did it go today? I asked.

He ignored the question, sat down next to me, and cupped my swollen breasts, weighed them like a medieval merchant.

Our Merry’s in musk, it seems, he said, laughing. I know what you’ll be wanting, he said, a finger burrowing inside my jeans. I was unwashed; I could smell myself on his fingers.

Have you been using the thermometer? he asked. You have to do it every day so we get the dates right.

A few weeks ago, he bought me a basal thermometer. I am supposed to take my temperature every morning and track the stages of my ovulation. Follicular phase, luteal phase, cycle length, everything recorded and set to a graph that displays on an app on my phone. Conception made science. When I am at my most fertile, the phone beeps frantically and a red circle appears on the screen. It’s a red day, it declares. A reminder. A warning.

I’m using it, I said. But it takes a while to work out your cycle.

He is impatient with me. He wants me pregnant again. Insisted we start trying when the baby was barely two months old.

It’s too soon, I begged. Everything hurts.

Nonsense, he said. The doctor said six weeks.

I would bleed afterward, shocked pink blood on the sheets and in my underwear the next day. Several pairs I deposited straight into the trash, the blood stiff and dried brown, smelling strongly of rust and decay.

Come, Sam said. He led me to the bedroom, set me down gently, with purpose.

I lay there and pretended to enthuse. Oh, yes. More. Please. He likes it when I beg. When I say thank you afterward, like he has given me a gift.

Some days it is harder than others to remember gratitude. To acknowledge my awful good luck. Sam went slow, stopping to look into my eyes. He repulses me sometimes. A physical reaction to his smell and his touch; the way he breathes through his mouth with his tongue lifted up, the way the hairs on his shoulders sprout in odd patches of wiry black strands.

Something inside me heaves and shudders to have him close.

I suppose that’s normal.

I love you, Merry, he said, and then I did feel it. Grateful. Loved. Or at least I think it’s what I felt. Sometimes it’s hard to know for sure.

Sam on top, inside, he clutched at me with both hands and breathed into my ear.

Let’s make a baby, he said, right before he came.

Sam (#ulink_b8870998-652f-508c-9b93-b3c145987564)

I was up early this morning, shaved, dressed, half out the door. Merry was setting Conor down in his high chair.

Where are you going?

Uppsala again, I said. I told you a few days ago.

You didn’t, she said.

It’s okay, I said, giving them each a quick kiss. You probably just forgot. You know how bad your memory can be.

You’re going again?

It’s a callback, I said. A meeting with the executive creative director this time.

She nodded. Good luck.

In the car, I checked the time, then my phone.

10 a.m., I wrote.

I pulled out of the drive and headed slowly past the neighboring houses. Mr. Nilssen was out with the horses. I raised my hand in greeting. He’s supposedly a billionaire. Sells his horses to the Saudis but still drives a Honda. God, I love the Swedes. Gives me a thrill every morning, driving out, seeing where we live and how. The sheer good fortune of it all. Sometimes you get lucky, I guess.

The day was going to be a good one. Sunny and clear. The traffic was smooth.

In forty minutes, I was outside her apartment door, ringing the doorbell.

You’re early, she said when she opened up. She was wearing a dress, ivory satin, tied tightly against her so it looked like she’d been submerged in thick cream. Her hair was loose, long, and blond and softly curled at the shoulders.

Hello, Malin. I smiled.

Come inside, she said.

Later, around the boardroom table, I looked at six young Swedes as they watched my reel. It’s a mix of old footage from the field and some new material I’ve been working on in the studio I’ve set up for myself at home. It’s good work. I know my way around a scene. I’ve been told that I have an excellent eye for framing. That I’m a natural at this.