По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

The History of Don Quixote, Volume 1, Complete

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Then all we have to do,” said the curate, “is to hand them over to the secular arm of the housekeeper, and ask me not why, or we shall never have done.”

“This next is the ‘Pastor de Filida.’”

“No Pastor that,” said the curate, “but a highly polished courtier; let it be preserved as a precious jewel.”

“This large one here,” said the barber, “is called ‘The Treasury of various Poems.’”

“If there were not so many of them,” said the curate, “they would be more relished: this book must be weeded and cleansed of certain vulgarities which it has with its excellences; let it be preserved because the author is a friend of mine, and out of respect for other more heroic and loftier works that he has written.”

“This,” continued the barber, “is the ‘Cancionero’ of Lopez de Maldonado.”

“The author of that book, too,” said the curate, “is a great friend of mine, and his verses from his own mouth are the admiration of all who hear them, for such is the sweetness of his voice that he enchants when he chants them: it gives rather too much of its eclogues, but what is good was never yet plentiful: let it be kept with those that have been set apart. But what book is that next it?”

“The ‘Galatea’ of Miguel de Cervantes,” said the barber.

“That Cervantes has been for many years a great friend of mine, and to my knowledge he has had more experience in reverses than in verses. His book has some good invention in it, it presents us with something but brings nothing to a conclusion: we must wait for the Second Part it promises: perhaps with amendment it may succeed in winning the full measure of grace that is now denied it; and in the mean time do you, senor gossip, keep it shut up in your own quarters.”

“Very good,” said the barber; “and here come three together, the ‘Araucana’ of Don Alonso de Ercilla, the ‘Austriada’ of Juan Rufo, Justice of Cordova, and the ‘Montserrate’ of Christobal de Virues, the Valencian poet.”

“These three books,” said the curate, “are the best that have been written in Castilian in heroic verse, and they may compare with the most famous of Italy; let them be preserved as the richest treasures of poetry that Spain possesses.”

The curate was tired and would not look into any more books, and so he decided that, “contents uncertified,” all the rest should be burned; but just then the barber held open one, called “The Tears of Angelica.”

“I should have shed tears myself,” said the curate when he heard the title, “had I ordered that book to be burned, for its author was one of the famous poets of the world, not to say of Spain, and was very happy in the translation of some of Ovid’s fables.”

CHAPTER VII.

OF THE SECOND SALLY OF OUR WORTHY KNIGHT DON QUIXOTE OF LA MANCHA

At this instant Don Quixote began shouting out, “Here, here, valiant knights! here is need for you to put forth the might of your strong arms, for they of the Court are gaining the mastery in the tourney!” Called away by this noise and outcry, they proceeded no farther with the scrutiny of the remaining books, and so it is thought that “The Carolea,” “The Lion of Spain,” and “The Deeds of the Emperor,” written by Don Luis de Avila, went to the fire unseen and unheard; for no doubt they were among those that remained, and perhaps if the curate had seen them they would not have undergone so severe a sentence.

When they reached Don Quixote he was already out of bed, and was still shouting and raving, and slashing and cutting all round, as wide awake as if he had never slept.

They closed with him and by force got him back to bed, and when he had become a little calm, addressing the curate, he said to him, “Of a truth, Senor Archbishop Turpin, it is a great disgrace for us who call ourselves the Twelve Peers, so carelessly to allow the knights of the Court to gain the victory in this tourney, we the adventurers having carried off the honour on the three former days.”

“Hush, gossip,” said the curate; “please God, the luck may turn, and what is lost to-day may be won to-morrow; for the present let your worship have a care of your health, for it seems to me that you are over-fatigued, if not badly wounded.”

“Wounded no,” said Don Quixote, “but bruised and battered no doubt, for that bastard Don Roland has cudgelled me with the trunk of an oak tree, and all for envy, because he sees that I alone rival him in his achievements. But I should not call myself Reinaldos of Montalvan did he not pay me for it in spite of all his enchantments as soon as I rise from this bed. For the present let them bring me something to eat, for that, I feel, is what will be more to my purpose, and leave it to me to avenge myself.”

They did as he wished; they gave him something to eat, and once more he fell asleep, leaving them marvelling at his madness.

That night the housekeeper burned to ashes all the books that were in the yard and in the whole house; and some must have been consumed that deserved preservation in everlasting archives, but their fate and the laziness of the examiner did not permit it, and so in them was verified the proverb that the innocent suffer for the guilty.

One of the remedies which the curate and the barber immediately applied to their friend’s disorder was to wall up and plaster the room where the books were, so that when he got up he should not find them (possibly the cause being removed the effect might cease), and they might say that a magician had carried them off, room and all; and this was done with all despatch. Two days later Don Quixote got up, and the first thing he did was to go and look at his books, and not finding the room where he had left it, he wandered from side to side looking for it. He came to the place where the door used to be, and tried it with his hands, and turned and twisted his eyes in every direction without saying a word; but after a good while he asked his housekeeper whereabouts was the room that held his books.

The housekeeper, who had been already well instructed in what she was to answer, said, “What room or what nothing is it that your worship is looking for? There are neither room nor books in this house now, for the devil himself has carried all away.”

“It was not the devil,” said the niece, “but a magician who came on a cloud one night after the day your worship left this, and dismounting from a serpent that he rode he entered the room, and what he did there I know not, but after a little while he made off, flying through the roof, and left the house full of smoke; and when we went to see what he had done we saw neither book nor room: but we remember very well, the housekeeper and I, that on leaving, the old villain said in a loud voice that, for a private grudge he owed the owner of the books and the room, he had done mischief in that house that would be discovered by-and-by: he said too that his name was the Sage Munaton.”

“He must have said Friston,” said Don Quixote.

“I don’t know whether he called himself Friston or Friton,” said the housekeeper, “I only know that his name ended with ‘ton.’”

“So it does,” said Don Quixote, “and he is a sage magician, a great enemy of mine, who has a spite against me because he knows by his arts and lore that in process of time I am to engage in single combat with a knight whom he befriends and that I am to conquer, and he will be unable to prevent it; and for this reason he endeavours to do me all the ill turns that he can; but I promise him it will be hard for him to oppose or avoid what is decreed by Heaven.”

“Who doubts that?” said the niece; “but, uncle, who mixes you up in these quarrels? Would it not be better to remain at peace in your own house instead of roaming the world looking for better bread than ever came of wheat, never reflecting that many go for wool and come back shorn?”

“Oh, niece of mine,” replied Don Quixote, “how much astray art thou in thy reckoning: ere they shear me I shall have plucked away and stripped off the beards of all who dare to touch only the tip of a hair of mine.”

The two were unwilling to make any further answer, as they saw that his anger was kindling.

In short, then, he remained at home fifteen days very quietly without showing any signs of a desire to take up with his former delusions, and during this time he held lively discussions with his two gossips, the curate and the barber, on the point he maintained, that knights-errant were what the world stood most in need of, and that in him was to be accomplished the revival of knight-errantry. The curate sometimes contradicted him, sometimes agreed with him, for if he had not observed this precaution he would have been unable to bring him to reason.

Meanwhile Don Quixote worked upon a farm labourer, a neighbour of his, an honest man (if indeed that title can be given to him who is poor), but with very little wit in his pate. In a word, he so talked him over, and with such persuasions and promises, that the poor clown made up his mind to sally forth with him and serve him as esquire. Don Quixote, among other things, told him he ought to be ready to go with him gladly, because any moment an adventure might occur that might win an island in the twinkling of an eye and leave him governor of it. On these and the like promises Sancho Panza (for so the labourer was called) left wife and children, and engaged himself as esquire to his neighbour.

Don Quixote next set about getting some money; and selling one thing and pawning another, and making a bad bargain in every case, he got together a fair sum. He provided himself with a buckler, which he begged as a loan from a friend, and, restoring his battered helmet as best he could, he warned his squire Sancho of the day and hour he meant to set out, that he might provide himself with what he thought most needful. Above all, he charged him to take alforjas with him. The other said he would, and that he meant to take also a very good ass he had, as he was not much given to going on foot. About the ass, Don Quixote hesitated a little, trying whether he could call to mind any knight-errant taking with him an esquire mounted on ass-back, but no instance occurred to his memory. For all that, however, he determined to take him, intending to furnish him with a more honourable mount when a chance of it presented itself, by appropriating the horse of the first discourteous knight he encountered. Himself he provided with shirts and such other things as he could, according to the advice the host had given him; all which being done, without taking leave, Sancho Panza of his wife and children, or Don Quixote of his housekeeper and niece, they sallied forth unseen by anybody from the village one night, and made such good way in the course of it that by daylight they held themselves safe from discovery, even should search be made for them.

Sancho rode on his ass like a patriarch, with his alforjas and bota, and longing to see himself soon governor of the island his master had promised him. Don Quixote decided upon taking the same route and road he had taken on his first journey, that over the Campo de Montiel, which he travelled with less discomfort than on the last occasion, for, as it was early morning and the rays of the sun fell on them obliquely, the heat did not distress them.

And now said Sancho Panza to his master, “Your worship will take care, Senor Knight-errant, not to forget about the island you have promised me, for be it ever so big I’ll be equal to governing it.”

To which Don Quixote replied, “Thou must know, friend Sancho Panza, that it was a practice very much in vogue with the knights-errant of old to make their squires governors of the islands or kingdoms they won, and I am determined that there shall be no failure on my part in so liberal a custom; on the contrary, I mean to improve upon it, for they sometimes, and perhaps most frequently, waited until their squires were old, and then when they had had enough of service and hard days and worse nights, they gave them some title or other, of count, or at the most marquis, of some valley or province more or less; but if thou livest and I live, it may well be that before six days are over, I may have won some kingdom that has others dependent upon it, which will be just the thing to enable thee to be crowned king of one of them. Nor needst thou count this wonderful, for things and chances fall to the lot of such knights in ways so unexampled and unexpected that I might easily give thee even more than I promise thee.”

“In that case,” said Sancho Panza, “if I should become a king by one of those miracles your worship speaks of, even Juana Gutierrez, my old woman, would come to be queen and my children infantes.”

“Well, who doubts it?” said Don Quixote.

“I doubt it,” replied Sancho Panza, “because for my part I am persuaded that though God should shower down kingdoms upon earth, not one of them would fit the head of Mari Gutierrez. Let me tell you, senor, she is not worth two maravedis for a queen; countess will fit her better, and that only with God’s help.”

“Leave it to God, Sancho,” returned Don Quixote, “for he will give her what suits her best; but do not undervalue thyself so much as to come to be content with anything less than being governor of a province.”

“I will not, senor,” answered Sancho, “specially as I have a man of such quality for a master in your worship, who will know how to give me all that will be suitable for me and that I can bear.”

CHAPTER VIII.

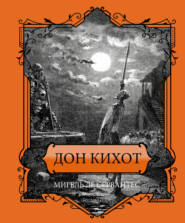

OF THE GOOD FORTUNE WHICH THE VALIANT DON QUIXOTE HAD IN THE TERRIBLE AND UNDREAMT-OF ADVENTURE OF THE WINDMILLS, WITH OTHER OCCURRENCES WORTHY TO BE FITLY RECORDED

At this point they came in sight of thirty forty windmills that there are on plain, and as soon as Don Quixote saw them he said to his squire, “Fortune is arranging matters for us better than we could have shaped our desires ourselves, for look there, friend Sancho Panza, where thirty or more monstrous giants present themselves, all of whom I mean to engage in battle and slay, and with whose spoils we shall begin to make our fortunes; for this is righteous warfare, and it is God’s good service to sweep so evil a breed from off the face of the earth.”

“What giants?” said Sancho Panza.

“Those thou seest there,” answered his master, “with the long arms, and some have them nearly two leagues long.”

“Look, your worship,” said Sancho; “what we see there are not giants but windmills, and what seem to be their arms are the sails that turned by the wind make the millstone go.”

“It is easy to see,” replied Don Quixote, “that thou art not used to this business of adventures; those are giants; and if thou art afraid, away with thee out of this and betake thyself to prayer while I engage them in fierce and unequal combat.”

So saying, he gave the spur to his steed Rocinante, heedless of the cries his squire Sancho sent after him, warning him that most certainly they were windmills and not giants he was going to attack. He, however, was so positive they were giants that he neither heard the cries of Sancho, nor perceived, near as he was, what they were, but made at them shouting, “Fly not, cowards and vile beings, for a single knight attacks you.”