По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

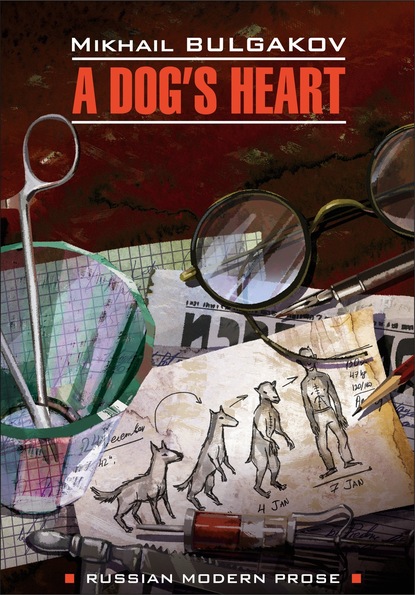

A dog's heart (A Monstrous Story) / Собачье сердце (Чудовищная история). Книга для чтения на английском языке

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The important canine benefactor turned abruptly on the step, leant over the banister, and asked in horror, “Really?”

His eyes opened wide and his moustache bristled.

The doorman tilted his head, brought his hand to his mouth and confirmed it. “Yes sir, a total of four of them.”

“My God! I can just imagine the state of the apartment now. And what did they say?”

“Nothing.”

“And Fyodor Pavlovich?”

“He went out for screens and bricks. To make partitions.”

“I’ll be damned!”

“They’ll be moving people into all the apartments, Filipp Filippovich, except yours. There was a meeting; they elected a new council of comrades and sent the old one packing.”

“The goings-on.[14 - The goings-on. – Что делается.] Ai-ai-ai… Phweet.”

I’m on my way, hurrying. My side is making itself felt, you see. Allow me to lick your boot.

The doorman’s gold braid vanished below. The marble landing was warm from the pipes, we turned one more time and reached the first floor.

Chapter 2

There’s absolutely no reason to learn how to read when you can smell meat a mile away. Nevertheless, if you live in Moscow and you have a modicum of sense in your head, you learn some reading willy-nilly, and without taking any courses. Of the forty thousand Moscow dogs there must only be one total idiot who can’t make out the word “sausage” syllable by syllable. Sharik started learning by colour. He had just turned four months when they hung greenish blue signs all over Moscow with the words “MSPO Meat Trade”[15 - MSPO Meat Trade – МСПО – мясная торговля]. We repeat, none of that is needed because you can smell meat anyway. And there was some confusion once: going by the toxic blue colour, Sharik, whose nose was masked by the petrol fumes of cars, ran into the Golubizner Brothers’ electrical-goods shop on Myasnitskaya Street instead of a butcher shop. There, at the brothers’ shop, the dog felt the sting of insulated wire, which is a lot tougher than a coachman’s whip. That famous moment should be considered the start of Sharik’s education. Back on the pavement, Sharik immediately understood that “blue” doesn’t always mean “meat” and, tucking his tail between his hind legs and howling with pain, he recalled that all the butchers’ signs started on the left with a gold or reddish squat squiggle that looks like a sled: “M”.

Things went more successfully after that. He learnt “A” from “Glavryba”, the fish store on the corner of Mokhovaya, and then the “B” (because it was easier to run over from the tail end of the word for fish, “ryba", since there always was a policeman standing at the beginning of the word).

Tile squares on the façades of corners in Moscow always and inevitably meant “Cheese”. The black tap of a samovar (the letter “Ch”) that started the word stood for the former owner Chichkin, mountains of Dutch red cheese, vicious salesmen who hated dogs, sawdust on the floor and the most vile, stinky Backstein cheese[16 - Backstein cheese – сыр бакштейн].

If someone was playing a concertina – which wasn’t much better than ‘Celeste Aida’ – and it smelt of hotdogs, the first letters on the white signs quite conveniently formed the word “Foul…” which meant: “Foul language not permitted and no tipping[17 - no tipping – на чай не давать].” Here brawls cycloned sporadically, people were punched in the face – albeit rarely – while dogs were beaten continually with napkins or boots.

If the windows displayed leathery hanging hams and piles of mandarin oranges, it was a delicatessen. If there were dark bottles with a bad liquid, it was a woof, wow.„w… ine store. The former Yeliseyev Brothers’ store.

The unknown gentleman, who had lured the dog to the door of his luxurious apartment on the second floor, rang and the dog looked up at the big card, black with gold letters, hanging to the side of the wide door with panes of wavy, rosy glass. He combined the first three letters right away: puh-ar-o – “Pro”. But then came a tubby, double-sided bitch of a letter that didn’t stand for anything he knew.[18 - a tubby, double-sided bitch of a letter that didn't stand for anything he knew: The Cyrillic letter F looks like this: Ф; the word being spelt out is “Professor”. (the translator’s note)]

“Could it be proletariat?” wondered Sharik doubtfully. “That can’t be.” He raised his nose and sniffed the fur coat once again, and thought confidently: “No, there’s no smell of the proletariat here. It’s a scholarly word, and God only knows what it means.”

Behind the rosy glass an unexpected and joyful light came on, casting the black card deeper into shadow. The door opened without a sound and a pretty young woman in a white apron and lace cap appeared before dog and man. The former was enveloped in divine warmth, and the woman’s skirt gave off the scent of lily of the valley.

“Now you’re talking, this is it,[19 - Now you’re talking, this is it – Вот это да, это я понимаю]” thought the dog.

“Please enter, Mr Sharik,” the man invited sarcastically, and Sharik entered reverently, tail wagg

g.

A great number of objects cluttered the rich entrance. The floor-length mirror that instantly reflected the second bedraggled and scruffy Sharik, the scary antlers up high, the endless fur coats and rubber boots and the opal tulip with electricity on the ceiling – all stuck in his head immediately.

“Where did you pick up this one, Filipp Filippovich?” asked the woman with a smile and helped him remove his heavy coat, lined with dark-brown fox with a bluish tinge. “Lord! What a mangy thing!”

“Nonsense. Where is he mangy?” the gentleman asked severely and gruffly.

Upon removing his fur coat, he appeared in a black suit of English cloth, and a gold chain twinkled happily and subtly across his belly.

“Just wait, stop wriggling, phweet. stop twisting, silly. Hmmm. That’s not mange. will you stand still, damn you!. Hmmm. Ah! It’s a burn. What bastard scalded you? Eh? Stand still, will you!”

“The cook, the criminal. The cook!” The dog spoke with his piteous eyes and whined a bit.

“Zina,” ordered the man, “bring him to the examining room and me my coat!”

The woman whistled and clicked her fingers and the dog, after a brief hesitation, followed her. Together, they entered a narrow, dimly lit corridor, passed a lacquered door and came to the end, and then went left and ended up in a dark cubbyhole, which instantly displeased the dog by its evil smell. The darkness clicked and turned into blinding daylight, and it sparkled, lit up, and turned white from all sides.

“Oh, no,” the dog howled mentally, “sorry, not for me! I get it! Damn them and their sausage! They’ve lured me into a dog hospital. They’ll force me to eat castor oil and they’ll cut up my side with knives, and it hurts too much to touch as it is!”

“Hey, no! Where do you think you’re going!” shouted the one called Zina.

The dog twisted away, coiled up, and then hit the door with its healthy side so hard that the whole apartment shuddered. Then he flew back, spun around in place like a top, and knocked over a white bucket that scattered clumps of cotton wool. As he spun, walls flew by, fitted with cupboards of gleaming instruments, and the white apron and distorted female face jumped up.

“Where are you going, you shaggy devil!” Zina shouted desperately. “Damn you!”

“Where’s the back stairs?” thought the dog. He reversed and smashed himself against the glass, hoping that it was a second door. A cloud of glass shards flew out with thunder and ringing, a tubby jar with reddish crap jumped out, spilling all over the floor and stinking up the room. The real door swung open.

“Stop! B-bastard!” The man shouted, jumping around in his white coat with only one sleeve on, and grabbed the dog by its legs. “Zina, hold him by the scruff of his neck, the scoundrel!”

“Wow! What a dog!”

The door opened even wider and another person of the male gender in a white coat burst in. Crushing broken glass, he rushed not towards the dog but the cupboard, opened it, and the whole room was filled with a sweet and nauseating odour. Then the person fell onto the dog with his belly, and the dog took pleasure in nipping him above the shoelaces. The person gasped but held on. The nauseating liquid filled the dog’s breathing and everything in his head spun, then he couldn’t feel his legs and he slid off somewhere sideways, crookedly.

“Thanks, it’s over,” he thought dreamily, falling right on the sharp pieces of glass, “farewell, Moscow! I’ll never see Chichkin and proletarians and Cracow sausages again! I’m going to Heaven for my canine suffering. Fellows, knackers, why did you do me in?”

And then he fell over on his side completely and croaked.

When he was resurrected, his head spun lightly and he had a bit of nausea in his belly, but it was if he had no side; his side was deliciously silent. The dog half-opened his right eye and out of the corner saw that he was tightly bandaged across his sides and belly. “They had their way after all[20 - They had their way after all – Все-таки отделали], the sons-of-bitches,” he thought woozily, “but cleverly, you have to give them that.”

“From Seville to Granada… in the quiet twilight of the nights,”[21 - From Seville to Granada… in the quiet twilight of the nights: The opening lines of the romance Don Juan's Serenade by Tchaikovsky, based on the poem by Alexei Tolstoy. (the translator’s note)] a distracted falsetto voice sang above him.

The dog was surprised; he opened both eyes fully and saw two steps away from him a man’s foot on a white stool. The trouser leg and long underpants were hiked up and the bare yellow shin was smeared with dried blood and iodine.

“Saints alive!” thought the dog. “That must be where I bit him. My work. They’ll whip me now!”

“‘Serenades abound, swords clash all around!’ Why did you bite a doctor, you mutt? Eh? Why did you break the glass? Eh?”

“Ooo-ooo-ooo,” the dog whimpered piteously.

“Well, all right, you’re conscious, so just lie there, you dummy.”

“How did you manage to lure such a nervous dog, Filipp Filippovich?” asked a pleasant male voice, and the knit underpants slid down. Tobacco smoke filled the air, and glass bottles rattled in the cupboard.

His eyes opened wide and his moustache bristled.

The doorman tilted his head, brought his hand to his mouth and confirmed it. “Yes sir, a total of four of them.”

“My God! I can just imagine the state of the apartment now. And what did they say?”

“Nothing.”

“And Fyodor Pavlovich?”

“He went out for screens and bricks. To make partitions.”

“I’ll be damned!”

“They’ll be moving people into all the apartments, Filipp Filippovich, except yours. There was a meeting; they elected a new council of comrades and sent the old one packing.”

“The goings-on.[14 - The goings-on. – Что делается.] Ai-ai-ai… Phweet.”

I’m on my way, hurrying. My side is making itself felt, you see. Allow me to lick your boot.

The doorman’s gold braid vanished below. The marble landing was warm from the pipes, we turned one more time and reached the first floor.

Chapter 2

There’s absolutely no reason to learn how to read when you can smell meat a mile away. Nevertheless, if you live in Moscow and you have a modicum of sense in your head, you learn some reading willy-nilly, and without taking any courses. Of the forty thousand Moscow dogs there must only be one total idiot who can’t make out the word “sausage” syllable by syllable. Sharik started learning by colour. He had just turned four months when they hung greenish blue signs all over Moscow with the words “MSPO Meat Trade”[15 - MSPO Meat Trade – МСПО – мясная торговля]. We repeat, none of that is needed because you can smell meat anyway. And there was some confusion once: going by the toxic blue colour, Sharik, whose nose was masked by the petrol fumes of cars, ran into the Golubizner Brothers’ electrical-goods shop on Myasnitskaya Street instead of a butcher shop. There, at the brothers’ shop, the dog felt the sting of insulated wire, which is a lot tougher than a coachman’s whip. That famous moment should be considered the start of Sharik’s education. Back on the pavement, Sharik immediately understood that “blue” doesn’t always mean “meat” and, tucking his tail between his hind legs and howling with pain, he recalled that all the butchers’ signs started on the left with a gold or reddish squat squiggle that looks like a sled: “M”.

Things went more successfully after that. He learnt “A” from “Glavryba”, the fish store on the corner of Mokhovaya, and then the “B” (because it was easier to run over from the tail end of the word for fish, “ryba", since there always was a policeman standing at the beginning of the word).

Tile squares on the façades of corners in Moscow always and inevitably meant “Cheese”. The black tap of a samovar (the letter “Ch”) that started the word stood for the former owner Chichkin, mountains of Dutch red cheese, vicious salesmen who hated dogs, sawdust on the floor and the most vile, stinky Backstein cheese[16 - Backstein cheese – сыр бакштейн].

If someone was playing a concertina – which wasn’t much better than ‘Celeste Aida’ – and it smelt of hotdogs, the first letters on the white signs quite conveniently formed the word “Foul…” which meant: “Foul language not permitted and no tipping[17 - no tipping – на чай не давать].” Here brawls cycloned sporadically, people were punched in the face – albeit rarely – while dogs were beaten continually with napkins or boots.

If the windows displayed leathery hanging hams and piles of mandarin oranges, it was a delicatessen. If there were dark bottles with a bad liquid, it was a woof, wow.„w… ine store. The former Yeliseyev Brothers’ store.

The unknown gentleman, who had lured the dog to the door of his luxurious apartment on the second floor, rang and the dog looked up at the big card, black with gold letters, hanging to the side of the wide door with panes of wavy, rosy glass. He combined the first three letters right away: puh-ar-o – “Pro”. But then came a tubby, double-sided bitch of a letter that didn’t stand for anything he knew.[18 - a tubby, double-sided bitch of a letter that didn't stand for anything he knew: The Cyrillic letter F looks like this: Ф; the word being spelt out is “Professor”. (the translator’s note)]

“Could it be proletariat?” wondered Sharik doubtfully. “That can’t be.” He raised his nose and sniffed the fur coat once again, and thought confidently: “No, there’s no smell of the proletariat here. It’s a scholarly word, and God only knows what it means.”

Behind the rosy glass an unexpected and joyful light came on, casting the black card deeper into shadow. The door opened without a sound and a pretty young woman in a white apron and lace cap appeared before dog and man. The former was enveloped in divine warmth, and the woman’s skirt gave off the scent of lily of the valley.

“Now you’re talking, this is it,[19 - Now you’re talking, this is it – Вот это да, это я понимаю]” thought the dog.

“Please enter, Mr Sharik,” the man invited sarcastically, and Sharik entered reverently, tail wagg

g.

A great number of objects cluttered the rich entrance. The floor-length mirror that instantly reflected the second bedraggled and scruffy Sharik, the scary antlers up high, the endless fur coats and rubber boots and the opal tulip with electricity on the ceiling – all stuck in his head immediately.

“Where did you pick up this one, Filipp Filippovich?” asked the woman with a smile and helped him remove his heavy coat, lined with dark-brown fox with a bluish tinge. “Lord! What a mangy thing!”

“Nonsense. Where is he mangy?” the gentleman asked severely and gruffly.

Upon removing his fur coat, he appeared in a black suit of English cloth, and a gold chain twinkled happily and subtly across his belly.

“Just wait, stop wriggling, phweet. stop twisting, silly. Hmmm. That’s not mange. will you stand still, damn you!. Hmmm. Ah! It’s a burn. What bastard scalded you? Eh? Stand still, will you!”

“The cook, the criminal. The cook!” The dog spoke with his piteous eyes and whined a bit.

“Zina,” ordered the man, “bring him to the examining room and me my coat!”

The woman whistled and clicked her fingers and the dog, after a brief hesitation, followed her. Together, they entered a narrow, dimly lit corridor, passed a lacquered door and came to the end, and then went left and ended up in a dark cubbyhole, which instantly displeased the dog by its evil smell. The darkness clicked and turned into blinding daylight, and it sparkled, lit up, and turned white from all sides.

“Oh, no,” the dog howled mentally, “sorry, not for me! I get it! Damn them and their sausage! They’ve lured me into a dog hospital. They’ll force me to eat castor oil and they’ll cut up my side with knives, and it hurts too much to touch as it is!”

“Hey, no! Where do you think you’re going!” shouted the one called Zina.

The dog twisted away, coiled up, and then hit the door with its healthy side so hard that the whole apartment shuddered. Then he flew back, spun around in place like a top, and knocked over a white bucket that scattered clumps of cotton wool. As he spun, walls flew by, fitted with cupboards of gleaming instruments, and the white apron and distorted female face jumped up.

“Where are you going, you shaggy devil!” Zina shouted desperately. “Damn you!”

“Where’s the back stairs?” thought the dog. He reversed and smashed himself against the glass, hoping that it was a second door. A cloud of glass shards flew out with thunder and ringing, a tubby jar with reddish crap jumped out, spilling all over the floor and stinking up the room. The real door swung open.

“Stop! B-bastard!” The man shouted, jumping around in his white coat with only one sleeve on, and grabbed the dog by its legs. “Zina, hold him by the scruff of his neck, the scoundrel!”

“Wow! What a dog!”

The door opened even wider and another person of the male gender in a white coat burst in. Crushing broken glass, he rushed not towards the dog but the cupboard, opened it, and the whole room was filled with a sweet and nauseating odour. Then the person fell onto the dog with his belly, and the dog took pleasure in nipping him above the shoelaces. The person gasped but held on. The nauseating liquid filled the dog’s breathing and everything in his head spun, then he couldn’t feel his legs and he slid off somewhere sideways, crookedly.

“Thanks, it’s over,” he thought dreamily, falling right on the sharp pieces of glass, “farewell, Moscow! I’ll never see Chichkin and proletarians and Cracow sausages again! I’m going to Heaven for my canine suffering. Fellows, knackers, why did you do me in?”

And then he fell over on his side completely and croaked.

When he was resurrected, his head spun lightly and he had a bit of nausea in his belly, but it was if he had no side; his side was deliciously silent. The dog half-opened his right eye and out of the corner saw that he was tightly bandaged across his sides and belly. “They had their way after all[20 - They had their way after all – Все-таки отделали], the sons-of-bitches,” he thought woozily, “but cleverly, you have to give them that.”

“From Seville to Granada… in the quiet twilight of the nights,”[21 - From Seville to Granada… in the quiet twilight of the nights: The opening lines of the romance Don Juan's Serenade by Tchaikovsky, based on the poem by Alexei Tolstoy. (the translator’s note)] a distracted falsetto voice sang above him.

The dog was surprised; he opened both eyes fully and saw two steps away from him a man’s foot on a white stool. The trouser leg and long underpants were hiked up and the bare yellow shin was smeared with dried blood and iodine.

“Saints alive!” thought the dog. “That must be where I bit him. My work. They’ll whip me now!”

“‘Serenades abound, swords clash all around!’ Why did you bite a doctor, you mutt? Eh? Why did you break the glass? Eh?”

“Ooo-ooo-ooo,” the dog whimpered piteously.

“Well, all right, you’re conscious, so just lie there, you dummy.”

“How did you manage to lure such a nervous dog, Filipp Filippovich?” asked a pleasant male voice, and the knit underpants slid down. Tobacco smoke filled the air, and glass bottles rattled in the cupboard.