По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

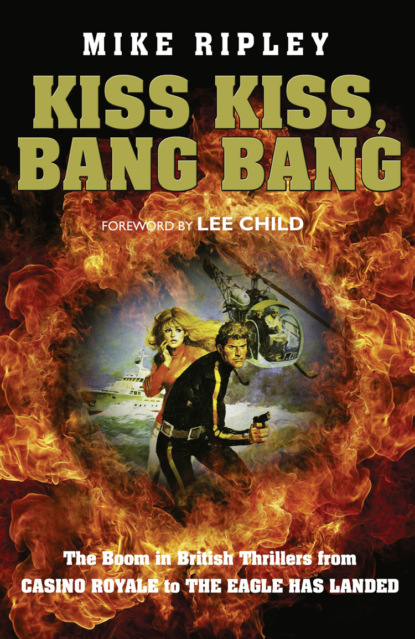

Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang: The Boom in British Thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Lyall’s early adventurers may have had military experience and certainly had some special, though not outlandish, skills in that they could drive expertly and could usually pilot an aircraft. They were not masters of disguise, almost certainly not versed in any martial art and relied on gadgets and secret equipment only to the extent that they knew how to use a spanner on a recalcitrant engine. They were the sort of guys other guys wouldn’t mind standing at a bar with, especially if those bars were abroad because Lyall’s heroes fitted in whether in Greece, Finland, France or the Caribbean, and would drink and eat what a regular guy would.

Fictional spies, of course, were on expenses when abroad and usually travelled first class, especially if they belonged to the Bond school of spy-fantasy. They tended to stay in five-star hotels, had limousines and drivers to meet them at the airport, drank the finest alcohol, ate in the finest restaurants – and could not resist giving the reader pointers on the art of foreign travel with style.

The Most Dangerous Game, Pan, 1966

James Bond was the first jet set secret agent – his early appearances in print coinciding with the establishment of commercial jet airline travel – and had seemed happiest when operating abroad. His missions had taken him to America, the Caribbean, Turkey, France, Switzerland and even Japan, with only one of his adventures – Moonraker – being set on home soil. The many candidates to replace Bond in the nation’s affections were just as keen to add to the collection of stamps and visas in their well-worn passports.

One of the leading pretenders to Bond’s throne was the extraordinary Dr Jason Love, who apart from being a country doctor in general practice, was skilled in martial arts and an authority on vintage cars – and he was always willing to help out British Intelligence at a moment’s notice, whenever or wherever needed. Created by James Leasor, Dr Love’s first outing was in Passport to Oblivion in 1964 and the action spread from Tehran and Rome to the wilds of northern Canada.

Further novels, usually with ‘passport’ in the title offering the prospect of foreign locales, followed with settings from Switzerland to the Himalayas, and the Bahamas to Damascus.

Hot on the heels of Dr Jason Love, 1964 also saw the arrival of Charles Hood, created by James Mayo, who was a clone of James Bond in in his love of the high-life but differed intellectually in that he was a connoisseur of, and dealer in, fine art. With such a day job, or perhaps cover story to maintain, it is of course necessary for Hood to spend quite a bit of time hanging around art galleries in Paris, though he does find time for excursions to the Windward Isles, Nicaragua and Iran in his 1968 adventure Once in a Lifetime, which was re-titled Sergeant Death when it appeared in paperback the following year.

Another 1964 alumnus of the academy of 007 substitutes was ‘barrister by profession, adventurer by choice’ Hugo Baron, created by John Michael Brett, who had a short fictional career working for an organisation known as DIECAST, which believed in violent means to achieve world peace and the elimination of espionage! Hugo Baron was clearly good at his job and duly found himself unemployed after three novels, though not before an adventurous jaunt to Egypt and Kenya in A Plague of Dragons in 1965.

Also making his debut in 1964 was John Craig, a distinctly working-class hero compared to most would-be Bond replacements. Created by James Munro (a pen-name of James Mitchell, who was to go on to invent the more famous David Callan) and appearing first in The Man Who Sold Death, Craig’s early adventures centred on the Mediterranean, the Middle East and Morocco but by The Innocent Bystanders in 1969 he was a paid-up member of the jet-set, zipping between New York, Miami, Turkey, and Cyprus.

Modesty Blaise, one of the few female not-so-secret agents created in the 1960s (or since) already had a cosmopolitan personal background when she first appeared in a newspaper comic strip in 1963 and then a series of novels (and one unlamented feature film) from 1965. Created by Peter O’Donnell, the independently wealthy Ms Blaise not only owns a villa in Tangiers but travels easily through Africa and the Middle East, and in Sabre-Tooth (1966) comes up against an army of terrorists training in Afghanistan in order to ferment revolt in Kuwait – a prescient, though twisted, mirror image of a very modern scenario.

Johnny Fedora, whose career timeline mirrored that of Bond, had already done his fair share of globe-trotting but by the 1960s, author Desmond Cory had settled him into a series of interwoven missions against his KGB nemesis based mostly in Spain.

Without doubt, though, the most popular foreign destination for British spies – though only the reader could be said to be the tourist – was Berlin.

A focal point of diplomatic tension between capitalist West and communist East since the 1940s, the isolated city of Berlin became the espionage hub of the Cold War when the ‘Anti-Fascist Protective Wall’ went up virtually overnight in 1961. A barrier dividing two opposing political systems, complete with armed guards, minefields, and checkpoints in the middle of a city already heavy with history and recent memories of a world war, it was a barrier that could only be crossed in secret ways and on pain of death, or in dramatic rituals of prisoner exchanges or spy ‘swaps’.

Walter Ulbricht, Head of State of East Germany, had created the ideal backdrop and sound stage for spy fiction and four bestselling novels in four years (1963–6) ensured that Berlin would become a film set as familiar to fans of spy stories as Monument Valley had been in the classic westerns of John Ford.

Although the bulk of the action takes place outside Berlin, the key opening and closing scenes of John Le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) take place around the Wall.

The tragic hero of the story, Alec Leamas, on his fateful mission into East Germany passes through one of the checkpoints in the Wall, under the watchful eyes of the ‘Vopos’ (Volkspolizei); the Mercedes he is riding in already being followed by a DKW.

The crossing is suspiciously incident-free.

As they crossed the fifty yards which separated the two checkpoints, Leamas was dimly aware of the new fortifications on the eastern side of the wall – dragon’s teeth, observation towers and double aprons of barbed wire. Things had tightened up.

The Mercedes didn’t stop at the second checkpoint; the booms were already lifted and they drove straight through, the Vopos just watching them through binoculars. The DKW had disappeared, and when Leamas sighted it ten minutes later it was behind them again. They were driving fast now – Leamas had thought they would stop in East Berlin, change cars perhaps, and congratulate one another on a successful operation, but they drove on eastwards through the city.

Getting in to East Berlin might have been easy for Alec Leamas, but leaving it, along with the girl he is rescuing, forms the excruciatingly tense and ultimately doomed finale to the novel. Leamas and Liz, the girl, are forced down the only escape route open to them: going over the Wall in the middle of the night, at a place swept by a searchlight where the guards have orders to shoot on sight. The last briefing from their contact arranging the escape is suitably grim.

‘Drive at thirty kilometres,’ the man said. His voice was taut, frightened. ‘I’ll tell you the way. When we reach the place you must get out and run to the wall. The searchlight will be shining at the point where you must climb. Stand in the beam of the searchlight. When the beam moves away begin to climb. You will have ninety seconds to get over. You go first,’ he said to Leamas; ‘and the girl follows. There are iron rungs in the lower part – after that you must pull yourself up as best you can. You’ll have to sit on the top and pull the girl up. Do you understand?’

‘We understand,’ said Leamas. ‘How long have we got?’

‘If you drive at thirty kilometres we shall be there in about nine minutes. The searchlight will be on the wall at five past one exactly. They can give you ninety seconds. Not more.’

‘What happens after ninety seconds?’ Leamas asked.

‘They can only give you ninety seconds,’ the man repeated.

In The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, John Le Carré was brilliantly describing the bleak topography of Cold War espionage, not a particular city. It was left to Len Deighton to give us the spy’s-eye view as his anonymous hero (‘Harry Palmer’ in the films) arrives for a Funeral in Berlin in 1964.

The parade ground of Europe has always been that vast area of scrub and lonely villages that stretches eastward from the Elbe – some say as far as the Urals. But halfway between the Elbe and the Oder, sitting at attention upon Brandenburg, is Prussia’s major town – Berlin.

From two thousand feet the Soviet Army War Memorial in Treptower Park is the first thing you notice. It’s in the Russian sector. In a space like a dozen football pitches a cast of a Red Army soldier makes the Statue of Liberty look like it’s standing in a hole. Over Marx-Engels Platz the plane banked steeply south towards Tempelhof and the thin veins of water shone in the bright sunshine. The Spree flows through Berlin as a spilt pail of water flows through a building site. The river and its canals are lean and hungry and they slink furtively under roads that do not acknowledge them by even the smallest hump. Nowhere does a grand bridge and a wide flow of water divide the city into two halves. Instead it is bricked-up buildings and sections of breeze block that bisect the city, ending suddenly and unpredictably like the lava flow of a cold-war Pompeii.

If there was ever a need for a tourist audio-guide to coming in to land at Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport (in 1964, that is), then surely Harry Palmer’s is the streetwise voice one would like to hear through the headphones. Over half-way through negotiating a labyrinthine plot of double- and triple-cross, our laid-back and very observant narrator still has time to add flashes of local colour, proving to the reader, thirsty for detail, that Palmer (and Deighton) had been there and seen that.

Funeral in Berlin, Penguin, 1966

The Quiller Memorandum, Fontana, 1967

Oddly enough, Berlin is one of the most relaxed big cities of the world and people were smiling and making ponderous Teutonic jokes about soldiers and weather and bowels and soldiers; for Berlin is the only city still officially living under the martial command of foreign armies and if they can’t make jokes about foreign soldiers no one can. Just ahead of me four English girls were adding up their holiday expenses, and deciding whether the budget would let them have lunch in a restaurant or if it was to be a Bockwurst sausage from a kiosk on the Ku-damm and eat it in the park. Beyond them were two nurses, dressed in a grey conventual uniform which made them look like extras from All Quiet on the Western Front.

Deighton was clearly at home in Berlin and it was to be a happy hunting ground for him – if not his characters – in the following decade.

For Adam Hall’s finely-tuned secret agent Quiller, who made his debut in The Berlin Memorandum (retitled The Quiller Memorandum when the film came out), the city was a very dangerous place, from its wintry streets, smoky bars, and seedy hotels and cafes to its lock-up garages (especially its lock-up garages!). Almost as soon as the super-tough Quiller arrives in Berlin to hunt neo-Nazis, he finds himself being hunted, on foot and by car. At one point he decides to give his pursuers a run for their money indulging, as Quiller himself puts it, in ‘a bit of healthy-schoolboy action’.

Slush was coming on to the windscreen and the wipers knocked it away. We made a straight run through Steglitz and Sudende because I wanted to know if they’d now make any attempt to close up and ram. They didn’t. They just wanted to know where I was going. I’d have to think of somewhere. Their sidelamps were steady in the mirror, a pair of pale fireflies floating along the perspective of the streets. We crossed the Attila-strasse and I made a dive into Ring-strasse going south-east, then braked to bring them right up behind me and make them slow. As soon as they had I whipped through the gears and increased the gap to half a block before swinging sharp left into the Mariendorfdamm and heading north-east towards Tempelhof. Then a series of dives through back streets that got them going in earnest. The speeds were high now and I had the advantage because I could go where I liked, whereas they had to think out my moves before I made them, and couldn’t, because I didn’t know them myself until the last second.

Clearly, in those far-off days before cars had sat navs, Quiller was the man to have behind the wheel when being tailed by the bad guys in Berlin.

It could be a pretty hostile place even if you were a Soviet double-agent trying to escape from the Western half to find sanctuary in the East, a clever inversion of the usual plot-line but exactly the scenario facing the character Alexander Eberlin in Derek Marlowe’s A Dandy in Aspic.

Eberlin got out with the other few tourists and curiosity seekers, and stood on the platform a moment taking stock. The blue-coated railway guards checked the compartments, and glancing up Eberlin could see, framed high on the metal catwalks of the roof, the silhouettes of two Vopos, immobile, machine guns resting on their hips. He had known of an East German youth who had tried to escape by clutching onto the roof of a train, and of another who had hid in the engine of a locomotive. Both had died on the journey. One shot from above, here, the other, untouched, unnoticed by the Vopos, entering the safety of the west as a charred, burnt-out body. But that was of no consequence to Eberlin. His journey was the other way, crossing the Wall as a mere tourist. A simple procedure.

By 1966 when A Dandy in Aspic was published and 1968 when the film came out

there would have been thousands of British thriller-readers who knew, quite confidently, that Eberlin’s journey would be far from simple. Fans of spy fiction, even those who had never been to Germany, knew all about Vopos, checkpoints, Tempelhof, ‘death strips’ around the Wall and the Ku-damm. They were well aware that everyone reading a newspaper on the street was a spy and every tobacconist’s kiosk was a dead letter drop.

There were many spy films in that peak period around 1966 and there would be many more thrillers set in Berlin both contemporary and historical, in the years to follow, but those four novels in quick succession by Le Carré, Deighton, Hall and Marlowe – all distinctively different in style – firmly established Berlin as the spy capital of the thriller world. Berlin’s reputation as a sort of espionage Camelot, where anything could happen and probably did, lasted until November 1989 when the Cold War began to thaw rapidly by popular demand with hardly a spy or a secret agent in sight.

1970s

As the 1970s dawned, it seemed that British thriller writers, albeit with some new faces joining the ranks of the bestselling, would continue to offer more of the same when it came to using foreign locations. For the writer of detective stories, particularly ‘police procedurals’, a familiar British (usually English) setting was thought necessary for realism. There were, back then, very few crime novels set abroad featuring local policemen, available either in translation or, daringly, written by British authors with specific knowledge of the country featured.

For the thriller writer, however, ‘abroad’ still meant ‘exciting’, even though British readers were availing themselves of cheap travel abroad and seeing more of the world via television and, more worryingly for the British writer’s sales figures, through the eyes of a new breed of American thriller writers. (Ironically perhaps, British thriller readers who liked their fictional thrills in foreign locations were introduced to American thriller writers through airport bookshops whilst waiting for their holiday flights.)

Both Graham Greene and Eric Ambler continued to offer foreign backdrops with customary professionalism and fluency; Greene setting The Honorary Consul (1973) in South America and Ambler again used the troubled Middle East for The Levanter, which won the Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger in 1972.

There was little sign, initially, that the two leading lights of the adventure thriller were running out of steam. Hammond Innes had been a published author since 1937 and Alistair MacLean since 1955, and neither seemed to have run out of new locations for their books.

MacLean donned his fur-lined parka once more and took us to the Barents Sea north of Norway and to Bear Island in 1971 and then switched to the sunny, though not safer, west coast of America for The Golden Gate

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: