По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

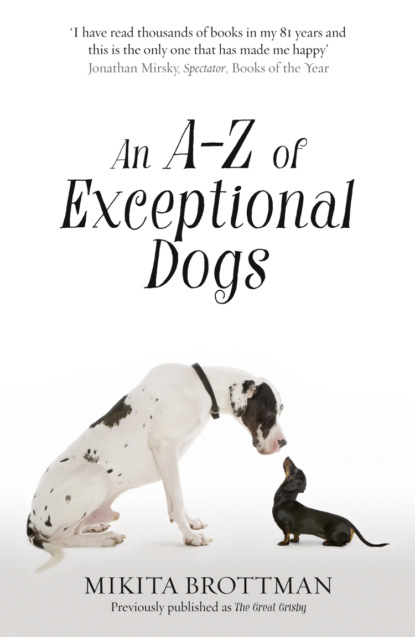

An A–Z of Exceptional Dogs

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When it was Albert’s turn to go to school in Bonn, Eos went with him, and when the prince married Victoria in 1840, at age twenty, the greyhound was sent ahead to Buckingham Palace in the care of her own personal valet. She’d grown into a fetching beast, black with white paws, a white underbelly, and a white tail tip. The newlyweds were both fond of animals and kept a number of dogs at court, but most of these belonged to the queen; Eos alone was decisively Albert’s dog. Six months after their marriage, the prince turned twenty-one, and in honor of the occasion, Victoria commissioned the royal jeweler, Garrard, to make an eight-by-ten-inch silver model of her husband’s greyhound (according to her diary, Albert was “much pleased” with his gift).

On their first anniversary, the queen presented Albert with another surprise: a portrait of Eos by the painter of animals Sir Edwin Landseer. This famous picture is entitled Eos, A Favourite Greyhound, Property of HRH Prince Albert, and it shows the dog posed against a rich red tablecloth, her muscles tense and rippling. Around her neck is a royal red-and-gold collar. With an eager and servile expression, she guards her master’s top hat and gloves, which are laid out ready for him on a hoof-footed, deerskin-covered stool. On a table behind the dog lies her master’s cane, topped with a red tassel and an ivory handle.

In terms of its pose, content, and composition, Eos, A Favourite Greyhound is regarded as an early example of the Victorian tradition of formal pet portraiture, but although the title describes it as a painting of Eos, it is, essentially, a portrait of Albert in absentia. The prince’s status and dignity are represented by his property: the eager bitch and the gentlemanly accessories. In light of the fact that Albert was himself sometimes dismissed as Victoria’s lapdog, perhaps the queen intended the painting as a form of subtle compensation. Either way, Albert was not offended; in fact, the portrait was so well received that she chose to commission another painting by Landseer for Albert’s next birthday, in 1842. In this picture, entitled Victoria, Princess Royal, with Eos, the new princess lies in her crib, and the greyhound—the prince’s other daughter—rests her slim snout protectively between the child’s bare feet. The dog’s gentle pose is perhaps deliberately reminiscent of the legendary hound Gelert, who gave his life to protect a royal baby (see HACHIKŌ (#u15b98ea3-8d41-56f9-a386-cf920889f9b3)).

Albert himself liked to paint and also dabbled in design. One of his more elaborate creations was commissioned over the winter of 1842–43, again in conjunction with Garrard: a colossal set of three gilded candelabra. The main part of this enormous ornament is a four-foot column whose base is decorated with carvings of Eos and three of Queen Victoria’s dogs: her Skye terrier Islay (“a darling little fellow, yellow brindled, rough long hair, very short legs and a large, long, intelligent good face”), her Scottish terrier Cairnach (“he had such dear engaging ways”), and her favorite dachshund, Waldmann. This grotesque gewgaw may have been too much even for Queen Victoria; the following year, it was unloaded on Viscount Melbourne, the former prime minister, on the occasion of his retirement, and it was known thereafter as the Melbourne Centerpiece.

From her portraits and sculptures, we know Eos was a sleek and dignified dog, but we know little about her personality or temperament other than a brief description included by Albert in a letter he wrote to Victoria from Germany before their marriage. In this letter, he describes Eos as “very friendly if there is plum-cake in the room … keen on hunting, sleepy after it, always proud and contemptuous of other dogs.” She may have been rather less keen on hunting after January 1842, when she was accidentally shot by Prince Ferdinand, a relative of Albert’s visiting from Germany. (“Favorites often get shot,” Lord Melbourne reassured the queen, adding that he “has known it happen often.”)

When the queen informed her uncle, King Leopold of Belgium, of the accident, he immediately replied to say how sorry he was to hear about what had happened to “dear Eos, a great friend of mine,” and expressed his annoyance at the culprit, Prince Ferdinand, suggesting that “he ought rather to have shot somebody else of the family.” The queen’s subsequent letters are full of information about the dog’s recovery and convalescence. On February 1, 1842, Victoria wrote that Eos “is going on well, but slowly, and still makes us rather anxious.” Four days later, she wrote to let her uncle know that “Eos is quite convalescent; she walks about wrapped up in flannel.”

Happily, the greyhound went on to live two more years after her injury, dying in 1844. Her demise may have been hastened by overindulgence. Shortly before the dog’s death, Victoria wrote to tell King Leopold that Eos had recently suffered from an “attack” that was attributed to “overeating (she steals wherever she can get anything), living in too warm rooms, and getting too little exercise.” She died very suddenly, after seeming quite well an hour before. Albert was devastated. “I am sure,” he wrote to his grandmother, “you will share my sorrow at this loss. She was a singularly clever creature, and had been for eleven years faithfully devoted to me.” Eos was buried beneath a mound above the slopes at Windsor Castle, the resting place of many royal pets before her. On hearing of her demise, Viscount Melbourne, perhaps alarmed that more hideous mementos might be forthcoming, declared himself “in despair at hearing of poor Eos,” but he was on safe ground: the Prince Consort limited himself to designing a life-size bronze monument marking the spot of the greyhound’s grave, and a second sculpture based on Landseer’s original portrait. “Poor dear Albert,” the queen wrote in her journal. “He feels it terribly, & I grieve so for him.” Grieving was something Victoria did well; her mourning for Albert, after he died in 1861, lasted almost forty years.

Even today, dogs are injured and sometimes killed in hunting accidents, though far fewer than in Albert’s day, thank goodness. Still, every age brings its own dangers, and whatever other concerns he may have had about Eos, at least Albert didn’t have to worry about her suffocating in the backseat of a car, overheating in an airplane cargo compartment, or drowning in a swimming pool—all accidents to which, as I know only too well, bulldogs are especially prone. The last of these dangers is perhaps my greatest anxiety, at least in relation to Grisby. It’s obvious these top-heavy dogs aren’t natural swimmers. Their bodies don’t bend in the middle, and their legs can’t paddle fast enough to keep them afloat. “Do not allow your bulldog near water!” warns the author of How to Raise and Train a French Bulldog. “He will sink like a stone!”

But dogs are individuals just as people are, and the fact is, some bulldogs love to swim, just as others—as YouTube amply testifies—love to skateboard, dive, ride on the back of motorcycles, and rock out to the blues. Grisby happens to be one of those dogs that just love water (though he doesn’t like rain and flees from the tub). The first time we took him to a beach, he ran straight into the sea and began to do an odd kind of doggy paddle. Despite his manifest enthusiasm, however, he’s too heavy to keep himself above the surface for long, and I’m always worried about him getting in over his depth.

For two years we lived in California, renting a beautiful ranch-style house with a pool in the backyard. At first, I was kept awake at night by the thought of coming home from work only to find my bulldog’s dead body at the bottom of the pool. And for a while, it seemed my fears were justified—on two occasions, after watching us dive into the deep end, Grisby, wanting in on the fun, did the same thing. Luckily, these two soakings seemed to work as shock therapy; after that, he seemed afraid of the pool and, apart from occasionally growling at the floats, wouldn’t go near it. I couldn’t even get him to sit in the shallow end to cool off. He preferred to snooze under my deck chair in the shade, and his happy snores gave me a good reason to stay lazing in the sun. (One of the many advantages of having a dog is that it gives you an excuse for doing things that might seem too indulgent if you were doing them alone. “I don’t like to disturb the dog,” you can tell yourself as you linger another hour in bed or at the beach.)

Back home on the East Coast, I take Grisby to the Chesapeake Bay to escape the summer heat. Our favorite beach is just a twenty-minute drive from the city; it’s free, easily accessible, and totally deserted. Here’s the catch: it’s filthy. For most people, this would be a deal breaker, but dogs are different. It’s true that the water is cloudy and the sand strewn with plastic debris, but none of that bothers Grisby, so it doesn’t bother me. One of the many things he’s reminded me of is that it’s more fun to be dirty than clean. He loves the smells and textures of trash, and he spends hours digging for buried chicken bones and discarded sandwiches. We spend many summer mornings on our special dirty beach, sunbathing, swimming together, dozing, and searching for treasure. At times, I have to veto Grisby’s playthings—used diapers and dead fish are going too far—but in short, I’ve learned to love a beach with dog-friendly detritus.

Speaking on behalf of Grisby, filth is fun, and it’s a rare dog that looks forward to bath night. Charles Robert Leslie, a nineteenth-century royal academician, wrote in his autobiography that when Victoria returned from her coronation, she heard her spaniel barking in the hall, and was apparently “in a hurry to lay aside the sceptre and ball she carried in her hands, and take off the crown and robes, to go and wash little Dash.” It’s hard to imagine the older Victoria washing her many dogs, and equally difficult to imagine the dignified Prince Albert bathing Eos. On the other hand, I can’t imagine the stately Eos bounding, as Grisby did recently, into a stagnant cemetery pond and emerging covered in stinking graveyard mud (naturally, he climbed into my lap in the car and sat there steaming and reeking all the way home). I also can’t help wondering whether Eos ever actually did guard Albert’s possessions, as she does in the Landseer portrait, or whether the picture’s composition is purely symbolic. Another question that’s crossed my mind is whether Albert struck his dog with the same cane Eos is carefully guarding; according to the biographer Jules Stewart, the prince “took a severe hand to his children’s upbringing” and “could easily sink into ill-temper.”

Grisby’s never been known to guard any of my possessions, though since we go for a run together every week, he’s grown especially attached to my running shoes (so much could be said about what shoes signify to dogs), not only because they’re sweatier and smellier than most of my other shoes but also because they speak his language; he knows what they mean. Thomas Mann observed a similar skill in his dog Bashan: “He sees what my intentions are. My clothes betray these to him, the cane that I carry, also my attitude and expression, the cool and preoccupied look I give him, or the irritation and challenge in my eyes. He understands.” Heatstroke is another anxiety when we go running since, like other flat-faced breeds, bulldogs are particularly susceptible to overheating and should be watched in hot weather (we never leave home without water, and I’m well versed in snout-to-mouth resuscitation). Still, he seems pretty resilient, and when he’s well and truly beat, he’ll flop down in the shade and refuse to move. Unlike many of us, he knows what he can take.

Our running loop in Baltimore is in a wooded area of Druid Hill Park behind the zoo, where, although we’re right in the center of the city, we’ll sometimes encounter foxes, deer, box turtles, and rat snakes. On our run, we follow a densely wooded path, which sometimes, after a storm, will get blocked by a fallen tree. When this happens, I climb over the trunk, and Grisby follows me, usually with a little trepidation, half jumping, half climbing, and landing on the ground each time with a satisfying snort.

With jogging as with walking, Grisby likes to keep his own pace; sometimes he’ll run ahead of me, sometimes he’ll fall behind. He likes to investigate wayside smells, chase squirrels and rabbits, take shortcuts, and greet strangers. On this particular path, people generally have their dogs off leash, and we always go early, when we’re least likely to run into people who might not appreciate a French bulldog’s exuberant greeting. For this reason, too, we stick to the more secluded areas of the park. The northern end, which contains some of the oldest forest growth in the state of Maryland, is a natural wooded habitat. Here, undergrowth covers a crumbling man-made pond, and the roads are closed to traffic. Sometimes we meet stray dogs wandering around in the woods; there’s apparently a small feral population, mostly pit bulls; they’ve all been friendly so far.

Our morning run, when we have one, is always the best part of my day. Nothing ever goes wrong. Grisby’s enthusiasm is never dampened. Then I go home or to work, and life goes on in the usual fashion, which is to say it’s full of drawbacks, hesitations, disappointments, arguments, and anxieties, the kinds of things that never bother me when I’m running with Grisby. I love being in the park with him; he loves being there with me. It’s really as easy as that.

[6] (#ulink_8b53092e-7d0c-5055-8d47-1f78459c9710)

FLUSH (#ulink_8b53092e-7d0c-5055-8d47-1f78459c9710)

“HE & I ARE inseparable companions,” wrote Elizabeth Barrett of her cocker spaniel, Flush, “and I have vowed him my perpetual society in exchange for his devotion.” The poet kept her promise and remained committed to her pampered spaniel until he died, at a healthy old age. Her loyalty was, she wrote, the very least she could do, since Flush had “given up the sunshine for her sake.”

The young spaniel was originally a gift from Elizabeth Barrett’s friend Mary Mitford in 1842, given partly to help ease the poet’s grief after losing two of her brothers in one year and partly to relieve her loneliness, as she was bedridden with symptoms of consumption. When Flush arrived in her life, Barrett, aged thirty-five, was spending almost all her time in an upstairs room in her family’s London home at 50 Wimpole Street; her delicate health meant she rarely saw anyone other than her immediate family and their household servants. The popular perception of Barrett before her marriage, like that of her contemporary Jane Welsh Carlyle (see NERO (#litres_trial_promo)), is of a lonely, childless, unhappy middle-aged woman for whom her dog was a compensation and substitute for human love, yet the situation of both women was far more subtle and indeterminate than this easy cliché suggests.

Flush is best known to us not through Barrett’s letters, in which he plays a major role, but through Virginia Woolf’s Flush: A Biography (1933), created, in part, as a playful parody of the popular Victorian life histories written by her friend Lytton Strachey—books like Eminent Victorians, Queen Victoria, and Elizabeth and Essex. In this charming story, told from the spaniel’s perspective, Woolf makes use whenever possible of Elizabeth Barrett’s and Robert Browning’s own words, drawn mainly from their letters. “This you’ll call sentimental—perhaps—but then a dog somehow represents—no I can’t think of the word—the private side of life—the play side,” she wrote to a friend, which perhaps explains why she later dismissed Flush as “silly … a waste of time.” Nevertheless, it remains one of her most popular books.

Part of the reason for its popularity, I’d suggest, is that Flush is really and truly about Flush, and not his human companions. Without wanting to generalize too much, I’ve noticed that dog books often have much more to say about humans than they do about dogs. In many cases, it seems, those who write about their dogs are actually writing about something else entirely—their families, their childhoods, or their bonds with nature. Or perhaps they’re writing about dogs as a way to remind us to appreciate the simple things in life, to enjoy the kinship claim of animals, or to accept the latter half of life with grace and dignity. In such books, the dog’s purpose is to catch the attention of the reader and, like Hitchcock’s famous MacGuffin, to drive forward the human plot. “Much more than a dog story,” reviewers will say, as if a dog story by itself is so very little.

In Woolf’s version of the tale, after a playful puppyhood spent in the English countryside, Flush soon reconciles himself to a quiet life with his invalid mistress, waking her in the morning with his kisses, sharing her meals of chicken and rice pudding soaked in cream. Elizabeth’s health improves when she meets Robert Browning, though Flush feels neglected at the intrusion, and can’t restrain himself from biting Browning in a fit of jealousy when he calls round one afternoon to pay a visit. Afterward, according to Elizabeth, Flush “came up stairs with a good deal of shame in the bearing of his ears.” His mistress refused to forgive him until eight o’clock in the evening, when, she writes to Browning, having “spoken to me (in the Flush language) & … examined your chair, he suddenly fell into a rapture and reminded me that the cakes you left, were on the table.”

Incidentally, Flush has no reason to complain of being displaced by Mr. Browning, whom Elizabeth loves very differently from the way she loves Flush. In many ways, the dog always comes first in her affections, but her love for Flush is more protective and maternal than erotic. Elizabeth writes to Mary Mitford that unlike other dogs, Flush dislikes bones; prefers sponge cake, coffee, and partridge cut into small pieces fed to him with a fork; and will drink only from a china cup even though it makes him sneeze. His mistress sheds tears when Flush is kidnapped—as actually happened three times in real life (see BULL’S-EYE (#ueb4475b8-a35f-5f7c-bc54-8d81da2e7107)), though Woolf conflates the events into one incident—yet her grief is considered ridiculous (“I was accused so loudly of ‘silliness & childishness’ afterwards that I was glad to dry my eyes & forget my misfortunes by way of rescuing my reputation”). She finds it necessary, in a letter to Browning, to justify her tears: “After all it was excusable that I cried. Flushie is my friend—my companion—& loves me more than he loves the sunshine.”

Men often seem to feel uncomfortable around “excessive” displays of emotion, especially those evoked by dogs. While he may not have ridiculed her tears, Robert Browning tried to persuade Elizabeth not to pay the ransom that was demanded for Flush when he was stolen. Elizabeth, in what was considered a reckless move by Browning and her family, went by carriage with Wilson, her maid, to the slums of Whitechapel to negotiate with the dog thieves. After five days and a payment of twenty pounds, much disapproved of by Barrett’s father and her fiancé, Flush was returned to Wimpole Street. It seems interesting to note in this context that Virginia Woolf’s husband, Leonard, appeared to share Robert Browning’s attitude. Though he loved dogs, Leonard Woolf took a Cesar Millan–style approach to their training, intimidating them into “calm submission” before offering any sign of friendliness. His method was hardly a great success—the Woolfs’ dog Hans was notorious for interrupting parties by getting sick on the rug, and Pinka, the dog Virginia Woolf used as the model for Flush, apparently ate a set of Leonard’s proofs and urinated on the carpet eight times in a single day.

According to the social reformer Henry Mayhew, stealing dogs was in fact a commonplace racket in Victorian London. “They steal fancy dogs ladies are fond of,” wrote Mayhew in 1861, “spaniels, poodles, and terriers.” Jane Welsh Carlyle, the wife of the essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle, was also a victim of these cruel swindlers (see NERO (#litres_trial_promo)). One day in June 1851, when Mrs. Carlyle was out walking with her husband and her Maltese dog Nero, “the poor little creature was snapt up by two men and run off with into space!” She doesn’t want to give in to the gang, she writes, “for if they find I am ready to buy him back at any price (as I am) they will always be stealing him—till I have not a penny left!” Nero was stolen and returned three times, once managing heroically to escape and make his way home under his own steam. Later in the same letter, however, we discover why the dog thieves had such an easy time of it. Mrs. Carlyle complains that she might have to start keeping Nero on a chain when they leave the house (“and that is so sad a Life for the poor dog”), an observation that suggests he was seldom leashed. While there was far less traffic at that time than there is today, and while horse-drawn vehicles rarely reached the speed of automobiles, there were surely plenty of opportunities for dogs to get into trouble, quite apart from being snatched up by kidnappers. Leashes may be a drag, but city dogs aren’t safe without them—in any century.

Barrett Browning never mentions any of her dreams, but since Flush slept in her bed (against doctor’s orders), he no doubt played an active role in her dream life. Grisby appears in my dreams all the time, though not always in his usual form (and in dreams, as in life, he has to be taken out to answer the call of nature). Once I dreamed there were two Grisbys, identical twins who sat under my chair like little Cerberuses. In another dream, a larger dog followed him around everywhere. When I asked this dog’s owner what his breed was, she replied, “He’s a shadowboxer.” This nocturnal doubling and shape-shifting seem unsurprising; as Freud himself remarks, in our dreams, “we are not in the least surprised when a dog quotes a line of poetry,” though when we wake, we can’t help trying to make sense of these strange transfigurations.

Most of my Grisby dreams, in fact, are nightmares—the expression, I assume, of all my repressed anxieties. They’re always the same, and they return me to a primitive, prelinguistic level of distress—the kind of primal pain experienced by the child taken from its mother, or by the mother who loses her child. In my nightmares, Grisby is missing. I’m devastated, torn between going in search of him and getting a new dog right away, to cushion the pain. Sometimes I do one, sometimes the other, but whenever I get a new dog, it’s always another male French bulldog, and I name him Grisby, too. Time passes. I grow to love my new Grisby. The old Grisby is forgotten. Then comes the moment of horror: All of a sudden, I realize the original Grisby’s still out there somewhere, all alone, lost, trying to get back to me. How could I have abandoned him? I’ll wake in a sweat, and it always takes me a moment to realize that Grisby is right there in bed with me—the original Grisby, whimpering in his sleep. Does he dream of losing me? Has he moved on to a new Mikita, leaving me lost, dogless, alone?

Flush, too, moves on. By the time the Brownings have settled in Florence, he’s grown accustomed to his new master, Robert, successfully making the transition from lapdog to family dog—something Grisby has never been able to do. Though he’s lived with David all his life, Grisby is, categorically, my pet. “Your French bulldog,” according to the author of How to Raise and Train a French Bulldog, “will bond with one member of the family,” a line that David often repeats in a slightly affronted tone.

In the wider culture, this exclusivity is largely considered unwholesome; I’ve heard Grisby called a “mommy’s boy,” and when I wear a long skirt, he sometimes likes to hide under it. It’s far healthier, according to popular opinion, for a dog to be part of the family. Family dogs are regarded as genial and good-natured, keeping guard over hearth and home. Free from pampering and protection, they romp with the kids each morning, nap in the sun all afternoon, then fetch Dad’s slippers when he gets home from work. Unsurprisingly, family dogs appear most often in children’s books, in which they love everyone unstintingly, demonstrating their loyalty by dragging old folks from burning buildings and saving kids from floods. Dogs like Lassie and Old Yeller spend their lives teaching families wonderful, life-enhancing lessons, and then, when they’re no longer needed, go gently to the grave.

Unlike the snippy, jealous lapdog, the family dog loves everyone, regardless of age. In J. M. Barrie’s play Peter Pan, Nana, a kind and docile black-and-white Newfoundland, keeps a close eye on the three Darling children, whose parents can’t afford a real nanny. When the children are flying away, Nana howls to alert their parents, but her warnings are ignored, leaving Mr. Darling so remorseful that he sleeps in the kennel himself, until their safe return. Nana, usually played by an actor in a dog suit, was based on Barrie’s own dog Luath, also a black-and-white Newfoundland, though, unlike Nana, Luath was a male. The author claimed he wrote Peter Pan “with that great dog waiting for me to stop, not complaining, for he knew it was thus we made our living.” Still, when Luath discovered he’d been given a sex change in the play, wrote Barrie, he couldn’t help expressing his feeling with “a look.”

Other family dogs care for the elderly. In John Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga, the dog Balthasar, a “friendly and cynical mongrel,” develops a close relationship with Old Jolyon, the family patriarch. Originally one of a litter of three puppies, all of which looked so wrinkled and old they were named after the three wise men, Balthasar is part Russian poodle and part fox terrier, “trying to be a Pomeranian.” The dog is found sitting protectively at Jolyon’s feet when the old man dies in his sleep one summer afternoon under a tree. In his own memoir, written in later life, Galsworthy meditates on the importance of dogs in his life, speculating that “it is by muteness that a dog becomes for one so utterly beyond value … When he just sits, loving and being loved, those are the moments that I think are precious to a dog.”

According to Colette Audry (see DOUCHKA (#u561fc870-80bd-5e8e-98e5-eb1fe8a82449)), certain breeds of dog are especially suited to this role. “Family men prefer poodles or cocker spaniels,” she writes, “harmless creatures chosen specially to amuse the children, ‘give them something to play with.’” As a feminist, Audry criticizes the way family patriarchs often reduce their underlings to the status of dogs. “The servant maintained a doglike silence, and the children romped about as though they were puppies,” she writes. “Inevitably, one’s love for one’s wife became confused, up to a point, with the feeling one had toward a favorite dog or horse.” Such a patriarch is the eccentric family farmer Dandie Dinmont in Walter Scott’s novel Guy Mannering. Dinmont owns six long-haired terriers (along with “twa couple of slow-hunds, five grews, and a wheen other dogs”) named “auld Pepper and auld Mustard, and young Pepper and young Mustard and little Pepper and little Mustard.” When asked whether this is not rather “a limited variety of names,” the farmer replies, “O, that’s a fancy of my ain to mark the breed, sir.” His fancy came true; this particular kind of long-haired terrier is now known as the Dandie Dinmont—the only example, to date, of a dog breed named after a literary character.

In Dickens’s Dombey and Son, the loving dog Diogenes, largely democratic in his affections, is passed among the Dombey family. Originally owned by the schoolmaster Dr. Blimber, Diogenes is taken up by Paul Dombey, then given to his sister, Florence, after Paul’s death, even though he is “not a lady’s dog, you know,” as Florence’s admirer Mr. Toots explains, euphemistically. Diogenes is “a blundering, ill-favored, clumsy, bullet-headed dog, continually acting on a wrong idea that there was an enemy in the neighborhood, whom it was meritorious to bark at,” and in order to get him into the cab to deliver him to Florence, Mr. Toots has to pretend there are rats in the straw. As soon as he’s released from the vehicle, Diogenes dives under the furniture in Florence’s house, dragging his long iron chain around the legs of chairs and tables, and almost garroting himself in the process.

Like many dogs in literature, Diogenes serves to indicate the character of the various people he encounters. Affectionate to Florence, Mr. Toots, Captain Cuttle, and Susan Nipper, he dislikes the sour Mrs. Pipchin and howls in her presence. Elsewhere the treatment of literary dogs can foreshadow human conduct. In Joyce Cary’s short story “Growing Up,” for example, the family patriarch returns from a business trip to find his young daughters appear unfamiliar and estranged. They express their violence first by mistreating Snort, the family dog, and then by turning on their father with homicidal aggression. This is the problem with being the household pet. If you belong to everybody, you belong to nobody, and you’re surely better off as a lapdog than a scapegoat, however undignified you might feel.

[7] (#ulink_0ffab782-ce0f-5663-a507-64c9fa247930)

GIALLO (#ulink_0ffab782-ce0f-5663-a507-64c9fa247930)

IT’S REMOTELY POSSIBLE that, during her final years in Florence, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s dog Flush might have encountered Giallo, the Pomeranian belonging to the English poet Walter Savage Landor, the Brownings’ friend and neighbor. In his younger days, Landor had lived in Florence for many years with his wife and children; he returned to England in middle age. Then, in 1858, as an old man of eighty-three, the poet found himself accused of libel, and escaped to Florence to avoid the resulting scandal. Here, the Brownings helped find accommodation close to their own home, the Casa Guidi, for this elderly gentleman and his frisky little dog.

In 1844, when he was living in Bath, Landor had a Pomeranian named Pomero, with fluffy white fur, bright eyes, and a yellow tail (Landor was said to be the model for Mr. Boythorn in Bleak House, with Pomero transformed into a canary). A friend who knew Landor said he concentrated on the dog “all the playful affectionateness that made up so large a portion of his character. He loved that noisy little beast like a child, and would talk nonsense to him as to a child.” “Not for a million of money would I sell him,” wrote the poet. “A million would not make me at all happier, and the loss of Pomero would make me miserable for life.” This loss came all too soon. “Seven years we lived together, in more than amity,” mourned Landor, after his pet’s death. “He loved me to his heart and what a heart it was! Mine beats audibly while I write about him.”

When the poet returned to Florence in later life, his friend the sculptor William Wetmore Story gave him another Pomeranian, and this affectionate creature, named Giallo after his yellow fur, became Landor’s closest companion for his remaining six years of life, causing him to be known by the locals as “il vecchio con quel bel canino” (“the old man with the beautiful dog”). Pomeranians are known for their loyalty and playful natures, but they also have less familiar advantages. In her 1891 essay “Dogs and Their Affections,” the English novelist Ouida wrote, “The Pomeranian is a most charming small dog, and … there is an electric quality in his hair which repels dust and dirt.”

In his lodgings on the Via Nunziatina, Landor soon became well known to English and American visitors, who described how Giallo’s white nose would push through the door ahead of his eccentric master, and how Landor would take a seat in his armchair and hold forth on politics and literature, attributing his most controversial opinions to his dog. “A better critic than Giallo is not to be found in all Italy, though I say it who shouldn’t,” he claimed. “An approving wag of his tail is worth all the praise of all the Quarterlies published in the United Kingdom.”

This popular and intelligent dog inspired many verses, including a couplet written on the occasion when Landor reached out and discovered his dog’s nose was hot (“He is foolish who supposes/Dogs are ill that have hot noses”). Giallo was also the subject of the touching poem “To My Dog,” written in August 1860, in which Landor acknowledged the fact that he would be in the grave long before his companion (“Giallo! I shall not see thee dead/Nor raise a stone above thy head”). He was right: Landor died in 1864, and Giallo lived on for another eight years in the care of his friend Contessa Baldelli. (“Poor dog! I miss his tender faithfulness,” wrote the contessa when Giallo finally died in 1872.)

Landor obviously enjoyed using his dog as a mouthpiece for controversial political and literary opinions. Since the poet’s sentiments were largely unpopular—he had a patrician contempt for the masses, for one thing—it was an inspired strategy to attribute his own words to a fluffy Pomeranian. As Virginia Woolf no doubt discovered while writing Flush, there’s a special pleasure to be had in putting words into a dog’s mouth—and many others have done so, though rarely with Woolf’s eloquence.

For the most part, canine correspondences are private games between friends or family members. On December 3, 1855, Jane Carlyle, the wife of Thomas Carlyle, noted in her diary that she wrote “a pretty long letter” from her dog Nero to her friend Mrs. Twisleton (“Oh Madam; unless I open my heart to someone; I shall go mad—and bite!”). The dogs in Sigmund Freud’s family “wrote” birthday poems to their master every year, rhymes that were actually composed by Freud’s daughter Anna. According to the author Roger Grenier, Marcel Proust wrote regular letters to Zadig, the dog that belonged to his lover Reynaldo Hahn (“My dear Zadig, I love you very much because you are soooo sad and full of love just like me”). It’s not difficult to interpret these communications as ways of expressing separation anxiety and other infantile feelings that are normally suppressed.

Things get more complicated, however, when people speak on their dogs’ behalf in a more public way, especially online. These days, there are thousands of journals on the Internet purportedly written by dogs, many linked to dog-themed social networking sites like Dogster or Dogbook (if Walter Savage Landor were alive today, he might well have blogged as Giallo). Their voices are uncannily similar: playful, enthusiastic, and endearingly dim-witted—the voice of a loving but backward child. This is also the personality attributed to Clark Griswold, the German shepherd star of a viral YouTube video in which the dog is teased playfully by his owner about not getting his favorite treats. Clark’s reactions, dubbed by his owner, are absurdly disconsolate. His engaging credulity is shared by the unnamed bulldog of the website Text from Dog, whose messages to his owner swing from engagingly exuberant (“I have to tell you … You accidentally fed me TWICE this morning … I GOT TWO BREAKFASTS … THIS IS THE GREATEST DAY OF MY ENTIRE LIFE”), to coyly passive-aggressive (“Who’s MORE important: ME or your girlfriend?”). There seems to be some kind of unspoken agreement that, in terms of personality, dogs are adorably dense (as opposed, perhaps, to smart, snooty cats).

According to Stanley Coren, a dog behaviorist and psychologist at the University of British Columbia, dog blogging is “a sign of affection,” and “trying to adopt a dog’s point of view can be a healthy exercise” for pet owners. “If we love them dearly, we’re always trying to crawl inside their heads and figure out what’s going on,” suggests Coren. “And if we love them dearly enough, we want other people to share in the dog’s expertise.” This, to me, seems an oddly disingenuous response to a phenomenon that begs for deeper consideration. Surely it’s obvious—is it not?—that these dog blogs do not actually “adopt a dog’s point of view” or “share a dog’s expertise.” The fact is, dogs have very little to do with them. These daily chronicles, with their infantilized voices, present-tense observations, and phonetic spellings, are produced by and for adult Homo sapiens. There are no pets online, just projections and displacements, human fantasies, and a willful return to the affections and appetites of childhood.

In Pack of Two, Caroline Knapp quotes Susan Cohen, the director of counseling at New York’s Animal Medical Center, who is fascinated by the way people talk about (and on behalf of) their dogs. “When someone offers what sounds like a human interpretation of a dog’s behavior,” says Cohen, “it gives you something to explore. It might not tell you a lot about the dog, but it helps tell you what the person is thinking, what they’re hoping, fearing, or feeling.” When the dog is owned by a couple, for example, its voice can be used by the “parents” to accuse each other of neglect (“Mommy found my long-lost tennis ball—you know, the one that Daddy lost and didn’t bother to replace”) or to portray themselves as unconditionally lovable (“Oh, Daddy’s dirty socks smell so good!”). At the most basic level, the “dog” here may be the blogger’s infant self, beloved by Mother without reservation, no matter how odd he or she might look or smell. In the purported form of a dog, the infant self can express needs and feelings that the adult ego might, with good reason, want to distance itself from. On the Internet, no one knows you’re not a dog.

The same dynamic also applies to in-person interactions. Arnold Arluke and Clinton R. Sanders note how pet owners, when “deciphering” their animal’s symptoms for veterinarians, will “explain” their companion’s moods (“She’s upset that we have a new baby”), speak dyadically (“We aren’t feeling well today”), or speak for the animal itself (“Oh, Doctor, are you going to give me a shot?”). Whether online or face-to-face, to speak in the voice of your dog is to engage in an act of self-deceiving ventriloquism, allowing you to be at the same time both beloved child and adoring parent. In this voice, you can buffer complaints, elicit apologies, confess wrongdoings, and mediate outlawed or forbidden impulses.

I can’t help noticing that I’m writing about “your dog,” analyzing what “people” do. Writing in the second or third person is another way to create distance from things that feel uncomfortable for us—that is, for me—to confess. The truth is, I’m so used to articulating Grisby’s preferences that it’s difficult to admit they’re not far from my own: He loves coffee cake but dislikes asparagus, likes cartoons but gets bored by foreign films, likes white bread but not tortillas. Moreover, last Christmas, writing in my left hand, I added “Grisby’s” shaky signature to mine and David’s at the bottom of our Christmas cards, reversing the R as if he were still learning to write. I’ve projected onto Grisby, it seems, the stereotype of a child with Down syndrome: comical, captivating, and always up for a cuddle.

Such children are famously lovable, but adults with the same condition are often shunned, especially since weight gain is a common side effect of neurological medication. Similarly, precocious children can be delightful, but infantile adults are disturbing, their sexual maturity sitting uncomfortably beside the child’s lack of self-restraint. In the same way, dog owners who write or speak as their dogs can do so comfortably only when their dogs are “fixed”; a blog or video giving human voice to a dog’s sexuality would be not cute but unsettling. Chop off his balls, however, and he can be a fat child forever.