По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

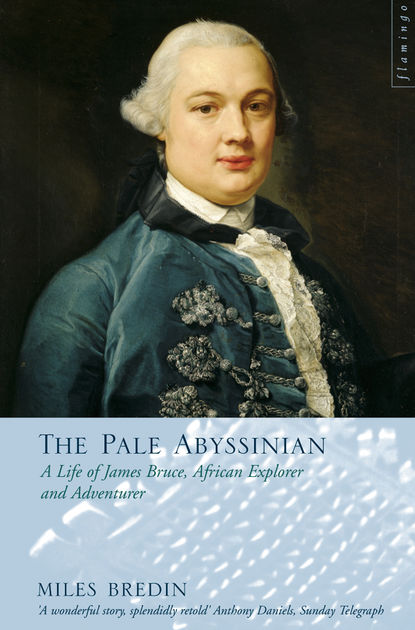

The Pale Abyssinian: The Life of James Bruce, African Explorer and Adventurer

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

This episode was really the last time Bruce had to act on behalf of the crown. It was almost a year before he left Algiers but, soon after Halifax’s letter of September, Bruce received notice that he would be replaced by Robert Kirke who would answer – unlike Bruce who had been neglected by him – to Captain Cleveland, the ambassador to all the Barbary States. Another treaty would be drawn up but Bruce would not be invited to help formulate it.

Slighted and beginning to believe the rumours that Cruise’s friends and Consul Duncan, the Dey’s representative at St James’s, had succeeded in blackening his name at home, Bruce devoted his days to hunting, training his gun dogs and getting himself properly equipped for the travels upon which it seemed he would now have to embark in a private capacity. He spent many hours interviewing traders and sailors, trying to find out all he could about the Red Sea and, when possible, Abyssinia. He studied his books and wrote to the Foreign Office seeking leave to depart his post, but even his most sycophantic letters received either no reply at all or replies that ignored his requests. By November he was engaged in undignified begging:

But as I hope your lordship thinks, from my attention to late transactions, I am not wholly unworthy of a small vacation, so I know it not to be unprecedented. Mr Dick, consul at Leghorn, received this permission while I was in Italy, though his journey had no other motive than that of pleasure, and I hope mine will not be unprofitable to the arts. There is, in this country, ruinous architecture enough to compose two considerable volumes. If, after obtaining this leave of absence, I could obtain another favour from your lordship, I should beg that I might have the honour to dedicate the first volume to the king, and that, from your lordship’s further goodness, I might have liberty to inscribe the second volume to your lordship.

He must desperately have been seeking leave to depart to have written so uncharacteristic a letter. But by now he was longing for travel and – rich enough to attempt it alone – he was as prepared as he ever would be. Throughout his time in Algiers he had acted in a dignified and resolute manner. It may not have been to the Dey’s liking from a commercial point of view but he could not help but admire the bluff Scotsman who refused to be bribed or intimidated. Thus he gave Bruce letters of introduction to his counterparts around the region which would make his tour of North Africa a great deal easier. Bruce’s friends Strange and Lumisden had also come up trumps: after much searching an artist had been found who would accompany Bruce for a year (he eventually stayed for six). Two others had considered the job but Lumisden had found it hard to persuade someone to ‘depart an easy life’ and embark for unknown shores. Strange wrote to say that Luigi Balugani – a fellow academician at Bologna – would accept the job.

This young man will be able to serve you in your present undertaking. He is certainly the best qualified of any I can find here. He has lived several years in Rome in the house of Conte Ranuzzi of Bologna. This gentleman gives him the best of characters to private life as well as diligence [an excellent recommendation since Bruce had met and liked Ranuzzi in Rome] … Balugani engages to serve you a year at the rate of 35 scudi a month. What he seems most defective in is figures, in which you must assist him yourself or have them afterwards retouched.

Balugani arrived in Algiers in March 1765 and in April Bruce was relieved of his duties. Cleveland came to Algiers with Robert Kirke and the pair ignored all Bruce’s advice to them, declining to meet him and even reappointing Cruise as vice-consul. It was a humiliation for the proud consul but he could not protest overmuch as it was what he himself desired. George Lawrence, the consul at Mahon, wrote to him: ‘Congratulations on getting rid of an employment which had so long become disagreeable to you.’ He had not been a very good consul though later commentators have been unnecessarily harsh.

The consulate was conferred on James Bruce solely to study antiquities in Africa [said Godfrey Fisher] and he was sent through France under a safe conduct to examine classical remains in Italy before reaching Algiers after the war. In spite of some likeable qualities, he was arrogant and irascible and, judging by his letters there may be some reason to question his mental stability. While he frantically summoned warships to his aid, he speaks in high terms of the Dey’s treatment of him … his successor complained that he had left ‘everything relative to publick affairs in much confusion and strangely neglected’.

This may be true although the British government, which had sent Bruce to study antiquities, surely had some share of the responsibility for his failure in a task he was neither trained for nor inclined to do. At least he was treated somewhat better than his predecessor and did well enough to get paid. The previous consul, Stanhope Aspinwall, spent five years in penury before he secured his pension, writing to Egremont (Halifax’s predecessor) in 1763:

Having been removed from being the King’s agent and consul at Algiers (in reaction to a letter from the Dey that I was unacceptable to him) without any the least previous notice, and left to get home as well as I could with a wife and numerous family, in winter and in time of war, I was many months in England soliciting the Earl of Bute but in vain …

Those following fared little better, for Algiers was a notoriously difficult post. The Dey often contrived to have consuls dismissed so as to leave him free to appoint his own. Kirke was soon recalled to Britain after Commodore Harrison, the Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean, reported him for corruption and dereliction of duty. Sir Robert Playfair (consul general in Algiers 100 years later and a Bruce enthusiast) wrote of the fate of Kirke’s successor, LeGros, who was driven to suicide by the difficulty of the posting: ‘He “met with a misfortune that made it impossible for him to execute that employment”, and the last we hear of him is that “he was sitting on a bed, with a sword and a brace of pistols at his side, calling for a clergyman to give him the Sacraments that he may die contented”.’

Bruce made sure that Halifax knew what he thought of his treatment: ‘I only very heartily regret with shame to myself that with my utmost diligence and attention I have not been able to merit of your Lordship the same marks of confidence constantly bestowed upon my predecessors in office,’ and in August he gave up diplomacy for good to set off on his travels. It was a chastened Bruce who left Algiers to record the ruins of ancient civilizations in which Halifax and the king had shown such interest: the merchants of Algiers heaved a collective sigh of relief.

The erstwhile consul first made for Mahon – just opposite Algiers, in the Mediterranean – where he had to attend to some ‘business of a private nature’. If, as seems likely, this was to do with Bridget Allan’s child it would have required all of his meagre diplomatic skills. His ‘housekeeper’ having died in quarantine on a visit from Algiers to Minorca, a man called Giovanni Porcile, who had been looking after the child, was demanding payment. Bruce was soon on his way back to Africa where he visited only a few ancient sites before going on to Tunis. He had learned the advantage of establishing credentials whilst in Algiers and wanted to meet the Bey before he started his exploratory tour. Carthage only occupied him for a few hours, since he knew he would be able to return with the Bey’s help whenever he wished. In Tunis, Barthélèmy de Saisieu, the French consul, provided him with a guide and ten ‘horse-soldiers, well armed with fire-locks and pistols, excellent horsemen, and, as far as I could ever discern upon the few occasions that presented, as eminent for cowardice, at least, as they were for horsemanship’. This small army proved to be quite useless when it was actually needed a few weeks later.

It was a fair match between coward and coward. With my company, I was enclosed in a square in which three temples stood [at the ruins of Spaitla], where there yet remained a precinct of high walls. These plunderers would have come in to me, but were afraid of my firearms; and I would have run away from them, had I not been afraid of meeting their horse in the plain. I was almost starved to death, when I was relieved by the arrival of Welled Hassan and a friendly tribe of Dreeda.

Bruce also had ten servants, two of whom were Irish slaves – Hugh and Roger McCormack – given him as a going away present by the Dey of Algiers (though formerly soldiers in the Spanish army, he was still referring to them as slaves a year later). He was also given a covered cart in which to put his astronomical instruments and other equipment; it was quite a caravan that made its way from Tunis inland, back towards Algiers. Bruce’s plan was twofold. He wanted to test his safari equipment – amongst which he doubtless included the artist Balugani – and he wished to record as many ancient ruins as he could. Thomas Shaw – an adventurous Oxford don and author of Travels or Observations Relating to Several Parts of Barbary and the Levant – had written about some of the ruins on the north coast of Africa but had missed out a great many others. Bruce wanted to venture where Shaw had not, paint pictures and then present the whole to the king, thus satisfying his own curiosity and simultaneously securing a peerage or a baronetcy for his dotage. They had permission to travel anywhere and took full advantage of it. They had two camera obscura, mirrored boxes, used contemporaneously by Canaletto, which by reflecting the scene on to paper allowed artists inside to trace exactly the outlines of the ruins they observed. It is astonishing how many paintings the two made: three bound volumes were given to George III on Bruce’s return. He kept some and gave others to friends. He quarrelled constantly with Dr Shaw’s artistic opinions: ‘There is at Thunodrunum a triumphal arch, which Dr Shaw thinks is more remarkable for its size than for its taste of execution; but the size is not extraordinary; on the other hand, both taste and execution are admirable,’ and criticized his work: ‘Doctor Shaw, struck with the magnificence of Spaitla, has attempted something like the three temples, in a style much like what one would expect from an ordinary carpenter or mason.’

Always contrary, Bruce was happy to have differences of opinion but he went out of his way to defend Shaw’s honour in the Travels, relating a story he knew would not be believed in order to show solidarity with his peer. At Sidi Booganim he came across a tribe which ate lions’ flesh. At the first opportunity, he tucked in: ‘The first was a he-lion, lean, tough, smelling violently of musk, and had the taste which, I imagine old horse-flesh would have … The third was a lion’s whelp, six or seven months old; it tasted, upon the whole, the worst of the three.’

Bruce was being deliberately provocative when he wrote about this in the Travels. Shaw had told a similar story when he had returned to Oxford twenty years earlier and no one had believed him. Now Bruce was doing the same. By the time of writing Bruce had also been severely criticized by those who did not believe him and, although he disagreed with Shaw on points of taste, he wanted to show solidarity on points of belief. This was an age when most people did not know what a lion looked like, save possibly in heraldry. Twenty-five years later Stubbs was to portray male lions stalking and tearing chunks out of horses – anatomically correct but not behaviourally so. Lions were still more mystical than real – they could only be seen by prisoners at the Tower of London – and no one could believe that men would or could eat the king of beasts. Thus, no one believed Bruce when he returned. Some of his stories – which seem unremarkable to us now – were judged too outlandish to be true. Bruce thus laboured the point in his book: ‘With all submission to that learned university, I will not dispute the lion’s title to eating men; but, since it is not founded upon patent, no consideration will make me stifle the merit of the Welled Sidi Boogannim, who have turned the chace [sic] upon the enemy.’

They continued their march up and down the Medjerda valley, through wheat fields that had fed ancient Rome, visiting Hydra and Constantina across lands which had seen Caesar and Hannibal, the Ptolemies and Pompey. Greeks, Romans, Egyptians – all had been there before him and left impressive traces in what, though described in ancient texts, was now the unknown world. Bruce noted all the ruins until the great amphitheatre at El Gemme, confident that the king would be grateful to his loyal subject. After all, it was not long ago that court painters and sculptors had been in the habit of depicting their kings in the guise of Roman emperors. Given the royal preoccupation with the lives of the ancient emperors and the current fascination with archaeology, these were ruins in which regal interest should be guaranteed and, accordingly, he did a thorough job: ‘I believe I may confidently say, there is not, either in the territories of Algiers or Tunis, a fragment of good taste of which I have not brought a drawing to Britain.’

They continued along the coast to Tripoli through territory that was disputed between the Basha of Tripoli and the Bey of Tunis. It was Bruce’s first taste of real desert travel and the journey, full of incident, was good training for the years ahead. In Tripoli they were met by one of Bruce’s myriad distant cousins:

The Hon. Mr Frazer of Lovat [After the débâcle of the suicidal consul at Algiers Archibald Campbell Fraser would eventually succeed Bruce.], his Majesty’s consul in that station, from whom I received every sort of kindness, comfort and assistance, which I very much needed after so rude a journey, made with such diligence that two of my horses died some days after.

Interestingly, whilst Bruce writes only about the death of two horses in his book, in a letter to Robert Wood he claimed that on the ‘night of the third day we were attacked by a number of horsemen, and four of our men killed upon the spot’. The version in the book is probably closer to the truth for in the letter (which he knew was not only for Wood’s eyes) he wanted to show what hardships he had suffered whilst painting the king’s pictures. He was no longer travelling on official business, of course, but he wanted the king and others to know that he had suffered for his art. Either way, the journey had been hard but also productive. They were not yet in uncharted territory but this was country where travellers had to look after themselves, thriving or withering according to their talents rather than their riches. On the expedition, Bruce learnt the rudiments of command, the dangers of travelling when the sun was high and had the need to be sufficiently prepared reinforced. They had encountered trouble because of Bruce’s impatience in not waiting for a letter of introduction to a tribal chief. He would not make the same mistake again.

From Tripoli, Bruce had to return by boat to Tunis where he stayed with the British representative, Consul Charles Gordon, another distant cousin. He doubtless saw his good friend Maria – an Italian in Tunis – about whom we know little but who continued to write her carissimo love letters for years afterwards. This was a convenient relationship for Bruce since Maria wrote that she had a jealous father and that Bruce should therefore never reply to her letters. He received the correct introductions to the Basha of Tripoli before setting off once more in August 1766 for Tripoli and Benghazi. Before doing so, however, he made sure that his paintings and notes from the first part of his journey were sent to Smyrna (Izmir) in the care of an English servant. He was now embarked on strenuous travels and did not want the extra burden of the hundreds of pictures he had completed. The future Libya was in a pitiable state: internecine warfare and famine made it a much more formidable destination than Tunis and Algiers. In Benghazi ‘ten or twelve people were found dead every night in the streets, and life was said in many to be supported by food that human nature shudders at the thought of’.

The general lawlessness exacerbated by famine meant that travel was not easy and Bruce only managed to see the principal sites of ancient Pentapolis, the ruin-bedecked area around Tolmeita and Benghazi that borders the Mediterranean. They too were recorded and written about with his usual fierce debunking of myth and legend. Soon, however, it became too hard to travel for so little reward – the ruins were more ruined even than those he had visited hitherto – and so in November they ‘embarked on board a Greek vessel, very ill accoutred’ for nearby Crete. It soon emerged that it was the captain’s first voyage and that he had no idea what he was doing. Within a few hours they were wrecked. Bruce described the mishap in his Travels: ‘We were not far from shore, but there was an exceeding great swell at sea.’ They tried to reach safety in a tender but that was soon swamped so Bruce threw himself into the sea crying, ‘We are all lost; if you can swim, follow me.’

‘A good, strong and practised swimmer’, he soon reached the surf but that was only the beginning of his problems; there was a riptide and he was beaten about by the waves for a good few minutes before he finally trod ground.

At last, finding my hands and knees upon the sand, I fixed my nails into it, and obstinately resisted being carried back at all, crawling a few feet when the sea had retired. I had perfectly lost my recollection and understanding, and after creeping so far as to be out of the reach of the sea, I suppose I fainted, for from that time I was totally insensible of any thing that passed around me.

Having prevailed against the sea and storm, he now had to prevail against the inhabitants who, like their Cornish contemporaries, saw a good shipwreck as manna from heaven, particularly when the victims were Turks as they suspected Bruce and his bedraggled, but miraculously alive, servants to be. Roasting in the hot sun, the semi-conscious Bruce had been stripped and bastinadoed before it occurred to him that he could speak his captors’ language – Arabic. As soon as he explained that he was a Christian doctor he was given succour by the local sheikh. It was, however, a sick and disconsolate Bruce who arrived back in Benghazi two days later. He was lucky that he had sent his earlier paintings on to Smyrna but even then it looked like his travels would be finished before he had even started. Much of his most essential equipment had been lost in the wreck.

I there lost a sextant, a parallactic instrument, a time-piece, a reflecting telescope [for astronomy], an achromatic one [for terrestrial observation], with many drawings, a copy of M. de la Caille’s ephemerides down to the year 1775, much to be regretted, as being full of manuscript marginal notes; a small camera obscura, some guns, pistols, a blunderbuss, and several other articles.

Without all these instruments Bruce would become the kind of traveller that he despised. He needed the equipment to legitimize his wanderings and give a purpose to his travels. In the age of Enlightenment it was no longer thought desirable to discover places unless they could be given co-ordinates and drawn on a map.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_4b0c0855-3caf-513d-9c4a-cd531dc35baa)

THE ENLIGHTENED TOURIST (#ulink_4b0c0855-3caf-513d-9c4a-cd531dc35baa)

Disgruntled and frustrated, Bruce arrived in Syria a few months later. His brush with death on the Barbary coast in 1766 was still bothering him the next year: he had done himself more harm than he had initially realized and the weak chest of his childhood was beginning to affect his life again. When he had eventually arrived in Crete on a more reliable vessel, he had been confined to his bed for months. Malaria, near drowning and the terrible buffeting he had received in the African surf were all conspiring to undermine his physical health. His mental state was none too good either. In the past few years he had failed as a diplomat and foundered as an explorer; if things did not look up soon he would have to steal back to England and marry Margaret Murray, then a child, now a mature woman, whom he had left behind with a miniature of himself for solace. He knew that Margaret was still waiting for him since he received the occasional letter from his friends in Rome giving him independent information about the lovesick girl. ‘I shall only add that little Murray and all your friends here remember you most affectionately,’ he had been told in a recent letter from Robert Strange.

In between bouts of ill health, he made the occasional trip with Balugani to see the sights of Syria, Cyprus and Turkey though most of the time he was seeing places already well-documented by others. This was, after all, Latin Syria where crusaders, pilgrims and latter-day knights had been living for centuries. His expeditions could do little other than satisfy his own curiosity and add more pictures to his already bulging portfolio. None of this adventuring was really worthwhile without the appropriate scientific instruments and they were very hard to come by. He had written to all his friends in France and England but they all encountered the same difficulty: ‘Everybody was employed in making instruments for Danish, Swedish, and other foreign astronomers; that all those which were completed had been bought up, and without waiting a considerable and indefinite time, nothing could be had that could be depended upon.’

This was depressing enough but he also received news that wild rumours about his travels were doing the rounds in England. It seemed he had become a laughing stock in his absence. To a man as proud as Bruce, this was worse than failure. ‘One thing only detained me from returning home; it was my desire of fulfilling my promise to my Sovereign, and of adding the ruins of Palmyra to those of Africa, already secured and out of danger.’

If he had known how completely uninterested George III was in the pictures he had been promised, he would have taken the first boat back to Dover. There were more important matters on the royal mind: this was the year when Clive departed India, leaving it in a state of complete chaos. Paintings would not have been uppermost in George’s thoughts. Bruce embarked for Syrian Tripoli where he went shooting and bought two hunting dogs – Juba and Midore – which, when not kennelled with Consul Charles Gordon, were to become devoted companions. In Tripoli he was told that to visit Palmyra he should approach from Aleppo which advice he immediately followed. After every journey he relapsed into ill health, but thankfully Aleppo was the best place in the Levant to do so, for there lived Patrick Russel, an English doctor who cured him, taught him medicine and became a lifelong friend. A plague specialist who had spent many years living in the Levant, he was well-versed in tropical illnesses and prepared a vast medicine chest for Bruce, which he then instructed him how to use. Russel and his brothers were excellent violinists who would play long into the night, and as Bruce danced with the local consuls, the French merchants and their wives, he began to recover. He also struck up new acquaintances: the Bellevilles and the Thomases, who were local traders, became firm friends. Bruce left Aleppo ‘in perfect health, and in the gayest humour possible’.

Palmyra had been visited before, most notably by his friend Robert Wood, but there was more work to be done both there and at nearby Baalbek, so having arranged the appropriate letters of introduction he set off to more adventures in the desert. He had an enjoyable and instructive time – it was ‘all classic ground’ – but he wrote little about it for fear of repeating the work of earlier travellers. More importantly, he disagreed with Wood. Not wanting to contradict his friend, he therefore set up his camera obscura, made some very beautiful paintings with Balugani, and returned to Aleppo two months later. Whilst he was away, exciting news had arrived from Europe. Patrick Russel’s brother Alexander had found him ‘an excellent reflecting telescope’ in London and also an achromatic one. Two time-pieces needed for taking longitude measurements had been sent from Paris to await Bruce’s arrival in Alexandria. They were not as good as his original Ellicott – a copy of Harrison’s 1760 chronometer which, through its ability to maintain accuracy over long periods, transformed navigation – but they would do. (Ellicott was one of the greatest clock-makers of the day, and among other things horologist to Catherine the Great.) This was great news indeed but Bruce recorded that it ‘still left me in absolute despair about obtaining a quadrant, and consequently gave me very little satisfaction’. In spite of this he decided to go to Egypt to visit the pyramids. The pyramids – a powerful image on all Masonic paraphernalia – were of special interest to him. It is a central tenet of Masonic lore that their founders built the pyramids.

Before he left, however, he received news he could never have anticipated. Abandoned by officialdom in his own country, it seemed that France was anxious to provide him with the necessary instruments to continue his travels. The fact that France and England were scarcely friends seems to have been overlooked when set against the aristocratic and masonic links that encouraged Bruce’s friends to help him and the lust for Enlightenment which was so much more entrenched in France than in Britain. His principal benefactor – the naturalist the Comte de Buffon, who was a member of the same lodge as Voltaire – managed to persuade the French government that the discovery of the source of the Nile was more important than whether the feat was achieved by an Englishman or a Frenchman.

The Comte de Buffon, Mons. Guys of Marseilles, and several others well known in the literary world, had ventured to state to the minister [the Duc de Choiseul who became a friend and had provided Bruce with his laissez-passer to travel through France on his way to Italy], and through him to the king of France, Louis XV, how very much it was to be lamented, that after a man had been found who was likely to succeed in removing that opprobrium of travellers and geographers, by discovering the sources of the Nile, one most unlucky accident, at a most unlikely time, should frustrate the most promising endeavours. That prince, distinguished for every good quality of the heart, for benevolence, beneficence, and a desire of promoting and protecting learning, ordered a military quadrant of his own military academy at Marseilles, as the nearest and most convenient port of embarkation, to be taken down and sent to me at Alexandria.

Bruce now had all he needed. In fact, he was rather better equipped than he had been in the first place, for he had just been given one of the best quadrants available – ‘reputed to be the most perfect instrument ever constructed in France’. He could straightaway devote himself entirely to discovering the source of the Nile; he had the money and the knowledge and he now had what money could not buy, the equipment with which to record his anticipated discoveries. He spent the winter with his friends in the Levant, preparing for his first venture into uncharted territory. He had learned the error of his ways and would not leave until he had all the permissions he could possibly need. His friend Murray, the ambassador to the Sublime Porte at Constantinople, managed to secure a firman (a letter of recommendation similar to a passport) from the Grand Signor at Constantinople which would prove invaluable; Bruce even acquired a letter to the Khan of the Tartars in case he became really lost. He had to solicit firmans for every eventuality and obtain letters of credit from his bankers in London as well as learn as much as he could about this momentous undertaking. He would still have difficulties if his firmans were not recognized or if he could find no one to honour his letter of credit, but the Arabic banking system was sophisticated and he could rely on it until he arrived in Abyssinia. His former colleagues, the British and French consuls in the area, were extremely helpful in this regard. He thus spent much of the winter writing bread and butter letters whilst others prepared the way for him.

Bruce planned to visit Alexandria, pick up his equipment and take it on a trial run to the pyramids. Then he would set off for Abyssinia through Massawa. Abyssinia’s littoral, including the Red Sea port of Massawa, was loosely under the control of the Sublime Porte. The only other way to reach the country was a long march via Sennaar in present-day Sudan. Having heard what had happened to the French ambassador du Roule in 1705, he was shy of going by way of Sennaar. Du Roule, the last man ever to have attempted an unannounced visit to the court of the King of Kings, took the Sennaar road and was murdered in the capital of the Fung kingdom. Massawa was an unknown quantity, unvisited by Europeans for 150 years, and Bruce would not go there until he was exhaustively prepared. As Bruce sat, dressed in the costume of a Barbary Arab, in the prow of a boat en route to Alexandria via Cyprus, he saw a high bank of clouds that he conjectured had come from the mountains of Ethiopia and would water the Nile. He was well-satisfied with his precautions.

Nothing could be more agreeable to me than that sight, and the reasoning upon it. I already, with pleasure, anticipated the time in which I should be a spectator first, afterwards an historian, of this phenomenon, hitherto a mystery through all ages. I exulted in the measures I had taken, which I flattered myself, for having been digested with greater consideration than those adopted by others, would secure me from the melancholy catastrophes that had terminated those hitherto unsuccessful attempts.

He first must needs make friends with the rulers of Egypt – the Mamelukes. Egypt was nominally ruled by the Turks but, under the recent onslaught of Catherine the Great, and after centuries of decadent rule, the Ottoman Empire was slowly crumbling. The Mamelukes were originally installed as a slave caste by rulers too lazy to govern themselves and as such had fought nobly against the crusaders and their descendants, but they had enjoyed greater and greater autonomy over the previous centuries. Indeed, Ali Bey, the present ruler, would declare himself an independent sultan the following year. Bruce was to be disappointed in the Mamelukes: ‘A more brutal, unjust, tyrannical, oppressive, avaricious set of infernal miscreants there is not on earth, than are the members of the government of Cairo.’

On 20 June 1768, after a five-day voyage, he made his first acquaintance with the Nile. At the mouth of the delta, by the ancient port of Alexandria, he was initially impressed by the near legendary city: ‘It is in this point of view the town appears most to advantage. The mixture of old monuments, such as the columns of Pompey, with the high Moorish towers and steeples, raise our expectations of the consequence of the ruins we are to find.’

To a man who had devoted so much of his life to learning about ancient civilizations, this must indeed have been a wonderful sight. He was at last seeing the things that he had heard and read described so many times by the ancients. Warming to his task, he surveyed the old port and gazed at the magnificent ruins. It was not long, however, before he resumed his customary sang-froid. Before he had even set foot on Egyptian soil, Alexandria had disappointed him.

But the moment we are in the port the illusion ends, and we distinguish the immense Herculean works of ancient times, now few in number, from the ill-imagined, ill-constructed, and imperfect buildings, of the several barbarous masters of Alexandria in the later ages … There is nothing beautiful or pleasant in the present Alexandria, but a handsome street of modern houses, where a very active and intelligent number of merchants live upon the miserable remnants of that trade, which made its glory in the first times.

Dressed as an Arab so as to be allowed where Europeans dared not tread, Bruce walked around the town, imbibing the atmosphere and providing inspiration for Richard Burton, who a century later would follow his example by donning Arab dress to visit Mecca and the Abyssinian Muslim stronghold of Harar. Despite being a very tall, red-haired man, Bruce managed, by wearing a turban and speaking perfect Arabic, to convince everyone that he was a peasant from the Barbary States. He was in good spirits. Two days before he arrived, an epidemic of the plague had petered out and, a few weeks earlier, Bruce’s astronomical instruments had been delivered. The Nile beckoned and at last he was able to respond: ‘Prepared now for any enterprise, I left with eagerness the thread bare enquiries into the meagre remains of this once famous capital of Egypt.’

With his entire band of servants dressed, like him, as Arabs, Bruce set off towards Rosetto on horseback – ‘We had all of us, pistols at our girdles’. Rosetto, midway between Alexandria and Cairo, was the embarkation point for travellers venturing up the Nile. The delta was dangerous and ‘besides, nobody wishes to be a partner for any time in a voyage with Egyptian sailors, if he can possibly avoid it’.

He arrived in Cairo on one of the Nile’s typical small sailing boats, a felucca, which were then known as canjas. Despite his appearance, he immediately set up house with a trader, M. Bertran, in the French quarter. By night he would dress as an English gentleman; by day he would venture, disguised, through the large gates which enclosed the foreign merchants’ street and patrol the bazaars of Cairo, buying manuscripts at Arabic prices and trying to find as much information about his route as was possible: ‘I never saw a place I liked worse, or which afforded less pleasure or instruction than Cairo’.

He did not have to stay in the source of his displeasure for very long, for yet again he was uncommonly lucky. The governance of Cairo lay all in the hands of one man, Ali Bey, whose closest confidant was an astrologer called Maalem Risk. The secretary of the Bey was ‘a man capable of the blackest designs’ but he was also most impressed by Bruce’s telescopes and quadrants. He passed Bruce’s baggage through customs, charging no duty, and introduced him to the Bey – ‘his turban, his girdle and the head of his dagger all covered with fine brilliants’.

Here Bruce’s expertise at dealing with Eastern rulers – learned at some risk in Algiers – came triumphantly into play. The correct amount of haughty arrogance combined with respect for the office and person of his host always seemed to come naturally to him. This and subsequent meetings allowed Bruce to make a few astrological predictions (something he did not believe in and usually disapproved of), and, by using Western medicine, to cure the Bey of a stomach upset, thus disposing the potentate towards him. Within a few weeks, he had been given his own house in the grounds of the seventh-century St George’s monastery outside the city and had been supplied with letters to the Naybe of Massawa, the King of Sennaar and the leaders of all the tribes he would encounter on his journey up the Nile. The Sardar of the Janissaries – chief of the mercenaries who policed the Turkish sultan’s vast empire – and the Greek Orthodox patriarch both gave him introductory letters also. It was a well-satisfied Bruce who cast off from Cairo on 12 December with his large retinue of servants and his friend Father Christopher, the former chaplain from Algiers, who had reappeared unexpectedly as an aide to Patriarch Mark of Alexandria.

Bruce had spent an unaccountably long time in Cairo considering he claimed to dislike it so. This goes unexplained in either his book, letters or journals. If he looked at the pyramids, he wastes less than a page on them in his book and feigns disinterest. They had, of course, been previously described by other travellers but even the most disenchanted tourist tends to write more than a postcard’s worth about them. His only comment in the Travels is that he thinks the stones for building them came from a more local source rather than the Libyan mountains, as was usually claimed. This is an odd omission and a mysterious, lost six months.

Bruce had rented himself a very beautiful felucca with ‘an agreeable dining room, twenty foot square’ for his cruise up the Nile. It did not quite rival that of the Ptolemies 2000 years earlier which boasted five restaurants, but it had an excellent captain, Abou Cuffi, who had been threatened with all sorts of horrors by the Bey if anything should happen to the good Hakim Yagoube (Doctor James). He had been made to leave one of his sons with the Bey ‘in security for his behaviour towards us’. Bruce’s successful treatment of the Bey had made him more ready to practise his medical skills and they became invaluable to him, not just for keeping himself and his servants healthy but also for gaining favours. He still acknowledged their value in his published thanks to Patrick Russel twenty years later – ‘My escaping the fever at Aleppo was not the only time in which I owed him [Russel] my life.’ From this point on, he always travelled as a doctor who practised for no payment – thus winning many friends – and in the words of the sultan’s firman as ‘a most noble Englishman and servant of the king’.