По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

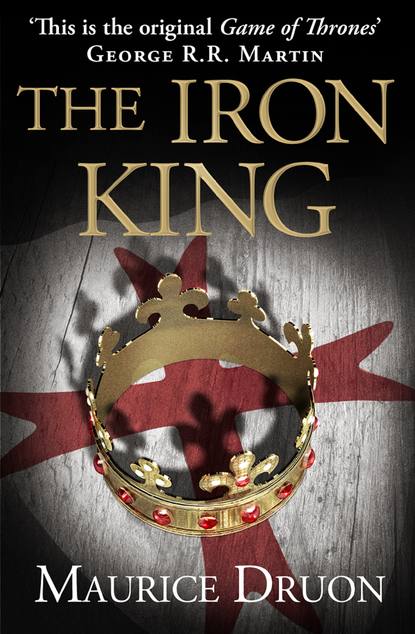

The Iron King

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Two courses of action,’ said Artois. ‘The first is to appoint to Madam Marguerite’s household a new lady-in-waiting who will be in our confidence and who will report to us. I have thought of Mme de Comminges for the post. She has recently been widowed and deserves some consideration. And in that your uncle Valois can help us. Write him a letter expressing your wish, and pretending to interest on the widow’s behalf. Monseigneur has great influence over your brother Louis and, merely in order to exercise it, will at once place Mme de Comminges in the Hôtel-de-Nesle. Thus we shall have a creature of ours on the spot, and as we say in military parlance, a spy within the walls is worth an army outside.’

‘I’ll write the letter and you shall take it back with you,’ said Isabella. ‘And what more?’

‘You must allay your sisters-in-law’s distrust of you; you must make yourself amiable by sending them nice presents,’ Artois went on. ‘Presents that would do as well for men as women. You can send them secretly, a little private friendly transaction between you, which neither father nor husbands need know anything about. Marguerite despoils her casket for a good-looking unknown; it would really be bad luck if, having a present she need not account for, we don’t find it upon the gallant in question. Let’s give them opportunities for imprudence.’

Isabella thought for a moment, then went to the door and clapped her hands.

The first French lady entered.

‘My dear,’ said the Queen, ‘please bring me the golden almspurse that the Merchant Albizzi brought me this morning on approval.’

During the short wait Robert of Artois for the first time ceased to be concerned with his plots and preoccupations and looked round the room, at the religious frescoes painted on the walls, at the huge, beamed roof that looked like the hull of a ship. It was all rather new, gloomy and cold. The furniture was fine but sparse.

‘Your home is not very gay, Cousin,’ he said. ‘One might think one was in a cathedral rather than a palace.’

‘I hope to God,’ Isabella said in a low voice, ‘that it does not become my prison. How much I miss France!’

He was struck by her tone of voice as much as by her words. He realised that there were two Isabellas: on the one hand the young sovereign, conscious of her role and trying to live up to the majesty of her part; and on the other, behind this outward mask, an unhappy woman.

The French lady-in-waiting returned, bringing a purse of interwoven gold thread, lined with silk and fastened with three precious stones as large as thumbnails.

‘Splendid!’ Artois cried. ‘This is exactly what we want. A little heavy for a woman to wear; but exactly what a young man at Court dreams of fastening to his belt in order to show off.’

‘You’ll order two similar purses from the merchant Albizzi,’ said Isabella to her lady-in-waiting, ‘and tell him to make them at once.’

Then, when the Frenchwoman had gone out, she added for Robert’s ear, ‘You’ll be able to take them back to France with you.’

‘No one will know that they passed through my hands,’ he said.

There was a noise outside, shouts and laughter. Robert of Artois went over to the window. In the courtyard a company of masons were hoisting to the summit of an arch an ornamental stone engraved in relief with the lions of England. Some were hauling on pulley-ropes; others, perched on a scaffolding, were making ready to seize hold of the block of stone, and the whole business seemed to be carried out amid extraordinary good humour.

‘Well!’ said Robert of Artois. ‘It appears that King Edward still likes masonry.’

Among the workmen he had just recognised Edward II, Isabella’s husband, a good-looking man of thirty, with curly hair, wide shoulders and strong thighs. His velvet clothes were dusty with plaster.

‘They’ve been rebuilding Westminster for more than fifteen years!’ said Isabella angrily. (She pronounced it Vestmoustiers, in the French manner.) ‘For the whole six years I’ve been married I’ve lived among trowels and mortar. They’re always pulling down what they built the month before. It’s not masonry he likes, it’s his masons! Do you imagine they even bother to say “Sire” to him? They call him Edward, and laugh at him, and he loves it. Just look at him.’

In the courtyard, Edward II was giving orders, leaning on a young workman, his arm round the boy’s neck. About him was an air of suspect familiarity. The lions of England had been lowered back to earth, doubtless because it was thought that their proposed site was unsuitable.

‘I thought,’ Isabella went on, ‘that I had known the worst with Sir Piers Gaveston. That insolent, boastful Béarnais ruled my husband so successfully that he ruled the country too. Edward gave him all the jewels in my marriage casket. In one way or another it seems to be a family custom for the women’s jewels to end up on men!’

Having beside her a relation and a friend, Isabella at last allowed herself to express her sorrows and humiliations. The morals of Edward II were known throughout Europe.

‘A year or so ago the barons and I succeeded in bringing Gaveston down; his head was cut off, and now his body lies rotting in the ground at Oxford,’ the young Queen said with satisfaction.

Robert of Artois did not appear surprised to hear these cruel words uttered by a beautiful woman. It must be admitted that such things were the common coin of the period. Kingdoms were often handed over to adolescents, whose absolute power fascinated them as might a game. Hardly grown out of the age in which it is fun to tear the wings from flies, they might now amuse themselves by tearing the heads from men. Too young to fear or even imagine death, they would not hesitate to distribute it around them.

Isabella had ascended the throne at sixteen; she had come a long way in six years.

‘Well! I’ve reached the point, Cousin, when I regret Gaveston,’ she went on. ‘Since then, as if to avenge himself upon me, Edward brings the lowest and most infamous men to the palace. He visits the low dens of the Port of London, sits with tramps, wrestles with lightermen, races against grooms. Fine tournaments, these, for our delectation! He has no care who runs the kingdom, provided his pleasures are organised and shared. At the moment it’s the Barons Despenser; the father’s worth no more than the son, who serves my husband for a wife. As for myself, Edward no longer approaches me, and if by chance he does, I am so ashamed that I remain cold to his advances.’

She lowered her head.

‘If her husband does not love her, a queen is the most miserable of the subjects of a kingdom. It is enough that she should have assured the succession; after that her life is of no account. What baron’s wife, what merchant’s or serf’s would tolerate what I have to bear … because I am Queen? The least washerwoman in the kingdom has greater rights than I: she can come and ask my protection.’

Robert of Artois knew – as indeed who did not? – that Isabella’s marriage was unhappy; but he had had no idea of the seriousness of the situation, nor how profoundly she was affected by it.

‘Cousin, sweet Cousin, I will protect you!’ he said warmly.

She sadly shrugged her shoulders as if to say: ‘What can you do for me?’ They were face to face. He put out his hands and took her by the elbows as gently as he could, murmuring at the same time, ‘Isabella …’

She placed her hands on the giant’s arms and said, ‘Robert …’

They gazed at each other with an emotional disturbance they had not foreseen. Artois had the impression that Isabella was making him some mute appeal. He suddenly found that he was curiously moved, oppressed, a prey to a force he feared to use ill.

Seen close to, Isabella’s blue eyes, under the fair arches of her eyebrows, were more beautiful still, her cheeks of a yet softer bloom. Her mouth was half open and the tips of her white teeth showed between her lips.

Artois suddenly longed to devote his days, his life, his body and soul to that mouth, to those eyes, to this delicate Queen who, at this moment, became once more the young girl which indeed she still was; quite simply, he desired her with a sort of robust immediacy he did not know how to express. In the ordinary way his tastes were not for women of rank and his nature was unsuited to the graces of gallantry.

‘Why have I confided all this to you?’ said Isabella.

They were still looking into each other’s eyes.

‘What a king disdains, because he is unable to recognise its perfection,’ said Robert, ‘many other men would thank heaven for upon their bended knees. Can it be true that at your age, fresh and beautiful as you are, you are deprived of natural joys? Can it be true that your lips are never kissed? That your arms … your body … Oh! take a man, Isabella, and let that man be me.’

Certainly he said what he wanted to say roughly enough. His eloquence bore little resemblance to the poems of Duke William of Aquitaine. But Isabella hardly heard him. He dominated her, crushed her with his mere size; he smelt of the forest, of leather, of horses and armour; he had neither the voice nor the appearance of a seducer, yet she was charmed. He was a man, a real man, a rugged and violent male, who breathed deep. Isabella felt her will-power dissolve, and had but one desire: to rest her head upon that leathern breast and abandon herself to him … slake her great thirst … She was trembling a little.

Suddenly she broke away from him.

‘No, Robert,’ she cried, ‘I am not going to do that for which I so much blame my sisters-in-law. I cannot, I must not. But when I think of what I am denying myself, what I am giving up, then I know how lucky they are to have husbands who love them. Oh, no! They must be punished, properly punished!’

In default of allowing herself to sin, her thoughts were obstinately bent upon the sinners. She sat down once more in the great oak chair. Robert came and stood by her.

‘No, Robert,’ she said again, spreading out her hands. ‘Don’t take advantage of my weakness; you will anger me.’

Extreme beauty inspires as much respect as majesty, and the giant obeyed.

But what had happened would never be effaced from their memories. For an instant the barriers between them had been lowered. They found it difficult not to gaze into each other’s eyes. ‘So I can be loved after all,’ thought Isabella, and she was almost grateful to the man who had given her this certainty.

‘Is that all you have to tell me, Cousin? Have you brought me no other news?’ she said, trying hard to regain control of herself.

Robert of Artois, who was wondering whether he was right not to pursue his advantage, took some time to answer.

He breathed deeply and his thoughts seemed to return from a long way off.

‘Yes, Madam,’ he said, ‘I have also a message from your uncle Valois.’

There was now a new link between them, and each word that they uttered seemed to have strange reverberations.