По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

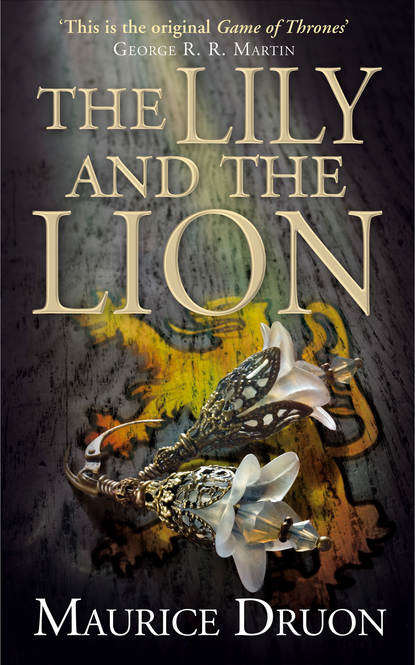

The Lily and the Lion

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Louis of Bourbon had been made a duke a few weeks before and had received the County of La Marche

as an apanage. He was the eldest member of the family. If the question of the Regency became dangerously controversial, the fact that he was Saint Louis’ grandson might well enable him to sway several votes. In any case, his views were bound to carry weight with the Council of Peers. He was not only lame but a coward; and it would require more courage than he possessed to enter the lists against the powerful Valois clan. Moreover, his son had married a sister of Philippe of Valois.

Robert gave Louis of Bourbon to understand that the sooner he promised his support, the earlier would all the lands and titles he had accumulated as a time-server during the previous reigns be guaranteed to him. He now had three votes.

The Duke of Brittany had hardly arrived from Vannes, and his trunks were not yet unpacked, when Robert of Artois called on him.

‘You agree on Philippe, don’t you? He’s so pious and loyal, we can be sure he’ll make a good king – I mean a good regent!’

Jean of Brittany was bound to support Philippe of Valois. After all, he had married one of Philippe’s sisters, Isabella. It was true she was dead, but he could hardly do other than be loyal to her memory. To lend weight to his overtures, Robert brought along his mother, Blanche of Brittany, the Duke’s elder sister. She was very old and small and wrinkled; but though her mind was far from lucid, she invariably agreed with everything her giant of a son said. Jean of Brittany was more concerned with the affairs of his duchy than with those of France. Since everyone seemed so much in favour of Philippe, why not?

It became a campaign of brothers-in-law. Reinforcements were called up in the persons of Guy de Châtillon, Count of Blois, who was not a peer, and Count Guillaume of Hainaut, who was not even French, because they had both married sisters of Philippe. The great Valois connexion was already beginning to look like the true family of France.

Guillaume of Hainaut was at this very moment marrying off his daughter to the young King of England; there appeared to be no disadvantage in this. Indeed, it might well prove a useful match. But he had been well advised to be represented at the wedding by his brother Jean instead of going himself, for it was here, in Paris, that events of real importance were under way. Guillaume the Good had long desired the lands of Blaton, an inheritance of the Crown of France forming an enclave within his estates, to be ceded to him. If Philippe became Regent, he should have Blaton for some merely symbolic quid pro quo.

As for Guy of Blois, he was one of the last barons to have the right to mint his own coinage. Despite this right, he was disastrously short of money and crippled with debts.

‘My dear Guy, your right to mint will be bought back from you by the Regency. It shall be our first care.’

Robert had done some very sound work in a remarkably short time.

‘You see, Philippe,’ he said to his candidate, ‘how useful the marriages your father arranged are to us now. People say that a lot of girls are a misfortune to a family; but that wise man, may God keep him, knew very well how to use all your sisters.’

‘Yes, but we shall have to complete the payment of the dowries,’ Philippe replied. ‘Only a quarter of what is due has been paid on several of them.’

‘My dear wife Jeanne’s to start with,’ Robert of Artois reminded him. ‘But when we have control of the Treasury …’

The Count of Flanders, Louis of Nevers, was more difficult to win over. For he was not a brother-in-law and wanted something more than mere lands or money. His subjects had driven him out of his county and he demanded that it should be reconquered for him. The price of his support was a promise of war.

‘Louis, my cousin, Flanders shall be restored to you by force of arms, we give you our word!’

Upon which Robert, who thought of everything, hurried off to Vincennes once again in order to press Charles IV to make his will.

Charles was merely the shadow of a king now, and was coughing up what remained of his lungs.

Yet, dying though he was, his mind was obsessed by the thought of the crusade that his uncle, Charles of Valois, had put into his head. The crusade had been abandoned; and then Charles of Valois had died. Could it be that his disease and the pain he was suffering were a punishment for having failed to keep his oath? His red blood staining the sheets reminded him that he had not taken up the cross to deliver the land in which our Lord had suffered his Holy Passion.

In an attempt to win God’s mercy, Charles IV therefore insisted on recording his concern for the Holy Land in his will: ‘For my intention,’ he dictated, ‘is to go there during my lifetime and, if that proves impossible, fifty thousand livres shall be allotted to the first general expedition to set out.’

This was not at all what was required of him, nor indeed that he should encumber the royal finances, which were urgently needed for more pressing matters, with such a mortgage. Robert was furious. That fool Charles was being stubborn to the last!

Robert merely wanted him to leave three thousand livres each to Chancellor Jean de Cherchemont, Marshal de Trye and Messire de Noyers, the President of the Exchequer, on account of their loyal services to the Crown – and, incidentally, because they sat on the Council of Peers by right of their appointments.

‘What about the Constables?’ murmured the dying King.

Robert shrugged his shoulders. Constable Gaucher de Châtillon was seventy-eight years old, deaf as a post, and so rich he did not know what to do with his money. You did not develop a sudden love of gold at his age. The Constable’s name was crossed out.

On the other hand, Robert proved most helpful to Charles in the matter of appointing executors, for this would establish a sort of order of precedence among the great men of the realm. Count Philippe of Valois headed the list, then came Count Philippe of Evreux, and then Robert of Artois, Count of Beaumont-le-Roger, himself.

Having dealt with the will, Robert now turned his attention to the spiritual peers.

Guillaume de Trye, Duke-Archbishop of Reims, had been Philippe of Valois’ tutor; and Robert had had his brother, the Marshal, put into the royal will for three thousand livres, which he made ring to good effect. There would be no difficulties in that direction.

The Duke-Archbishop of Langres had long been a supporter of the Valois, as had also Jean de Marigny, Count-Bishop of Beauvais, who had even betrayed his brother, the great Enguerrand, to serve the hatreds of the late Monseigneur Charles of Valois.

There remained the Bishops of Châlons, Laon and Noyon; and these, it was known, would follow Duke Eudes of Burgundy.

‘As for the Burgundian,’ cried Robert of Artois, with a wide sweep of his arms, ‘he’s your affair, Philippe. I can do nothing with him; we’re at daggers drawn. After all, you married his sister and you must be able to bring some pressure to bear on him.’

Eudes IV was no diplomatic genius. But he remembered the lessons he had learned from his mother, Agnes of France, the last surviving daughter of Saint Louis, who had died the preceding year, and how the determined old woman had succeeded in negotiating, during Philippe the Long’s regency, the reuniting of the County of Burgundy and the duchy. Eudes had then married Mahaut of Artois’ granddaughter, who was twenty-seven years younger than himself, but he no longer complained of this now that she was nubile.

The question of the Artois inheritance was the first subject he discussed with Philippe of Valois, when they were closeted together on his arrival from Dijon.

‘It is quite understood, of course, that at Mahaut’s death, the County of Artois goes to her daughter, Queen Jeanne the Widow, with remainder to the Duchess, my wife, is it not? I must make a point of this, Cousin, for I well know Robert’s pretensions to Artois; he has proclaimed them enough!’

These great princes were as bitter in defence of their right of inheritance to a quarter of the kingdom as were the daughters-in-law of the poor in squabbling over cups and sheets.

‘Judgement has twice been given assigning Artois to the Countess Mahaut,’ replied Philippe of Valois. ‘Unless any new facts come to light supporting Robert’s claim, Artois will go to your wife, Brother.’

‘You see no impediment?’

‘None at all.’

And thus the loyal Valois, the gallant knight, the hero of tournaments, had now given two contradictory promises.

Nevertheless, honest in his duplicity, he told Robert of Artois of his conversation with Eudes, and Robert wholly approved it.

‘The main thing,’ he said, ‘is to acquire Burgundy’s vote. What does it matter that he should feel secure in a right which is not his anyway? New facts, you said? Very well, we’ll produce some, and I won’t make you break your word. Don’t worry, it’s all for the best.’

They had now merely to wait for one last formality – the King’s death. It was to be hoped it would not be long delayed, for this splendid conjunction of princes in support of Philippe of Valois might not endure.

The Iron King’s last son died on the eve of Candlemas, and the news of his death spread through Paris the next morning, together with the odour of the hot flour of pancakes.

Robert of Artois’ plans seemed to be working perfectly when, on the very morning the Council of Peers was to be held, a thin-faced, tired-eyed English bishop arrived in a mud-stained litter to urge the claims of Queen Isabella.

3. (#ulink_486fe2e2-11f9-5ee6-b91f-db7cfad90de2)

A Corpse in Council (#ulink_486fe2e2-11f9-5ee6-b91f-db7cfad90de2)

THERE WERE NO BRAINS in the head now, no heart in the breast, nor entrails in the stomach. He was a hollow king. But, indeed, there was little difference between Charles IV alive and now that the embalmers had done their work. He had been a backward child, whom his mother had called ‘the Goose’, a cuckolded husband, and an unsuccessful father, for he had vainly, if stubbornly, endeavoured to assure the succession by marrying three times; he had also been a weak prince, first subject to an uncle and then to cousins, indeed but a fleeting incarnation of the royal entity.

On the state bed, at the far end of the great pillared hall of the Castle of Vincennes, lay his corpse, clothed in an azure tunic, a royal mantle about its shoulders and the crown on its head.

By the light of the massed candles, the peers and barons gathered at the other end of the hall could see the gleam of the corpse’s boots of cloth of gold.

Charles IV was presiding over his last Council, which was known as ‘the Council in the King’s Chamber’, for he was deemed to be ruling still. His reign would end officially only on the following day, when his body was lowered into the tomb at Saint-Denis.

Robert of Artois had taken the English bishop under his wing, while they waited for the latecomers.