По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

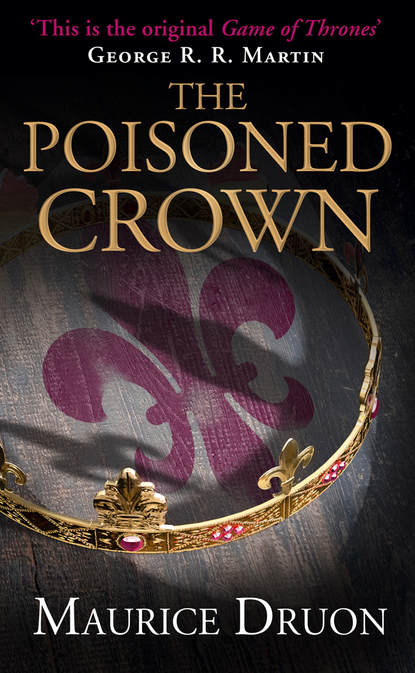

The Poisoned Crown

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘If we go into battle tomorrow, and a Hirson happens to be within arm’s reach of me, I can promise him a blow or two which will not necessarily have been given him by the Flemings,’ declared a fellow with huge red eyebrows who called himself the Sire de Souastre.

Rather drunk though he might be, Robert of Artois’s brain remained clear. So much wine dispensed, so many girls on offer, so much money spent, all had a reason. He was working to gratify his vengeance and advance his own affairs.

‘My noble lords, my noble lords, the King’s war must come first. We are his loyal subjects and he is, at this moment, I assure you, entirely sympathetic towards your just complaints,’ he said. ‘But when the war is over, then, Messeigneurs, I advise you not to disarm. To be on a war-footing with your vassals mobilized is a good opportunity, go back to Artois and chase Mahaut’s agents from the whole countryside, flog their backsides in the marketplaces of the towns. And I will support you in the King’s Council Chamber, and will reopen once again the lawsuit in which I was the victim of a travesty of justice; and I guarantee that you shall have your old customs back, as in the times of my father.’

‘That’s what we’ll do, Messire Robert, that’s what we’ll do!’

Souastre opened his arms wide.

‘Let us swear,’ he cried, ‘not to disperse before our demands have been granted, and our good Lord Robert has been given back to us as our Count.’

‘We swear it!’ the barons replied.

They embraced each other and many more bumpers were poured out; then torches were lit as night was drawing on. Robert of Artois felt a happy thrill of excitement running through his huge body. The league of Artois, which he had secretly founded and led for many months, was gaining strength.

At this moment an equerry came into the tent and said, ‘Monseigneur Robert, the commanders of “banners” are required immediately in the King’s tent!’

The torches spread an acrid smoke which mingled with the strong smell of leather, sweat, and wet iron. Most of the great lords, sitting in a circle about the King, had neither washed nor shaved for the last six days. Normally they would never have spent so long without going to the baths. But dirt was part of war.

The Constable Gaucher de Châtillon had just repeated for the commanders of ‘banners’ his report upon the disastrous situation of the army.

‘Messeigneurs, you have heard the Constable. I desire your counsel,’ said Louis X.

Putting his blue silk surcoat across his knees, Valois began speaking in his haranguing voice.

‘I have already told you, Sire, my Nephew, and now repeat it before everyone: we can no longer remain in this place where everything is going to rack and ruin, the men’s morale and the horses’ condition. Inaction is doing us as much damage as the weather.’

He interrupted his speech because the King had turned round to speak to his chamberlain, Mathieu de Trye; but it was only to ask for a sweet, which was handed him. He was always in need of something to chew.

‘Go on, Uncle, I pray you.’

‘We must move at dawn tomorrow,’ Valois went on, ‘find a ford by which to cross the river upstream, and fall upon the Flemings so as to defeat them before evening.’

‘With hungry men and unfed horses?’ said the Constable.

‘Victory will fill their stomachs. They can hold out for another day; but the day after tomorrow will be too late.’

‘I tell you, Charles, that you’ll either be drowned or cut to pieces. I see no alternative but to withdraw the army to high ground towards Tournai or Saint-Amand, so that the rations can reach us and the flood water have a chance to drain away.’

It often happens that as we mention lightning the skies thunder, or that someone enters the door at the very moment we are speaking ill of them. Coincidence seems malicious in the way it challenges our words.

At the very moment the Constable was counselling them to let the flood water drain away, the roof of the tent caved in over Monseigneur of Valois, who was soused. Robert of Artois, who was sitting in a corner smelling strongly of wine, began laughing and the King followed his example, which made Charles of Valois lose his temper.

‘We all know, Gaucher,’ he cried, rising to his feet, ‘that you are paid a hundred pounds a day while the King is with the army and that you have no wish to bring the war to an end.’

Wounded to the quick, the Constable replied, ‘It is my duty to remind you that even the King cannot decide to attack the enemy without the advice and orders of the Constable. And in the present circumstances I shall not give these orders. That being the case, the King can always change his Constable.’

An extremely painful silence ensued. The matter was a grave one. Would Louis X, to please Valois, dismiss the head of his armies, as he had dismissed Marigny, Raoul de Presles, and all Philip the Fair’s other ministers? The results of that policy had not been altogether happy.

‘Brother,’ said Philippe of Poitiers in his calm voice, ‘I entirely agree with the counsel Gaucher has given you. The troops are in no condition to fight till they have had a good week in which to recuperate.’

‘That is also my advice,’ said Count Louis of Evreux.

‘And so we are never to punish the Flemings!’ cried Charles de la Marche, the King’s second brother, who always shared his uncle Valois’s opinions.

Everyone began to speak at once. Retreat or defeat, that was their choice, the Constable affirmed. Valois replied that he saw no advantage in retreating fifteen miles merely that the army should continue to rot. The Count of Champagne announced that his troops, having been raised only for a fortnight, would return home if no attack were launched; and Duke Eudes of Burgundy, brother of the assassinated Marguerite, took advantage of the argument to show how little eager he was to serve his ex-brother-in-law.

The King remained hesitant, uncertain with which party to side. The whole expedition had been conceived as a rapid campaign. Both the condition of the Treasury and his personal prestige depended upon quick results. He saw the chances of a lightning war diminishing. To follow the path of wisdom and good sense, to regroup elsewhere and wait, was to postpone both his marriage and his coronation. Whereas to expect to be able to cross a river in flood and charge through the mud at a gallop ...

It was at this moment that Robert of Artois rose to his feet and, an impressive sight in his massive scarlet and steel, strode into the centre of the meeting.

‘Sire, my Cousin,’ he said, ‘I understand your concern. You have not enough money to maintain this huge army in idleness. Moreover, you have a new wife awaiting you, and we are all impatient to see her made Queen, as we are to see you crowned. My advice is not to persist. It is not the enemy that forces us to turn back; it’s in the rain I see the will of God before which everyone, however great he may be, must bow. Who can tell, Cousin, whether God has not wished to warn you not to fight before you have been anointed with holy oil? You will gain as much prestige from a fine coronation as from a rash battle. Therefore, renounce for the moment your intention of whipping these wretched Flemings, and if the terror with which you have inspired them is not in itself sufficient, let us come back with as great a force next spring.’

This unexpected advice, coming from a man whose courage in battle could not be doubted, received the support of part of the meeting. No one understood then that Robert was pursuing ends of his own, and that his desire of raising Artois was closer to his heart than the interests of the Kingdom.

Louis X, impulsive but not particularly prompt to act, was always ready to give up in despair when events did not turn out as he wished. He seized the lifeline Artois offered him.

‘You have spoken wisely, Cousin,’ he said. ‘Heaven has given us a warning. Let the army withdraw, since it cannot advance. But I swear to God,’ he added, raising his voice and thinking thus to preserve his grandeur, ‘I swear to God that if I am still living next year, I shall invade these Flemings and will make no armistice with them short of unconditional surrender.’

From that moment he had no concern but to break camp as quickly as possible, and his sole preoccupations were with his marriage and his coronation.

The Count of Poitiers and the Constable had considerable difficulty in persuading him to take certain indispensable precautions, such as maintaining garrisons along the Flanders frontier.

The Hutin was in such a hurry to be gone, as were most of the commanders of ‘banners’, that the following morning, since they lacked wagons and could not extract all their gear from the mud, they set fire to their tents, their furnishings, and equipment.

Leaving behind it a huge conflagration, the foundering army arrived before Tournai that evening; the terrified inhabitants closed the gates of the town, and no one insisted that they should open them. The King had to find asylum in a monastery.

Two days later, on August 7th, he was at Soissons, where he signed a number of Orders in Council which put an end to this distinguished campaign. He charged his uncle Valois with making the final preparations for his coronation, and sent his brother Philippe to Paris to fetch the sword and the crown. Everyone would gather between Rheims and Troyes to meet Clémence of Hungary.

Though he had dreamed of meeting his fiancée as a hero of chivalry, Louis’s only concern now was that the distressing expedition be forgotten, an expedition which was already known as ‘The Muddy Army’.

7 (#ulink_15757e77-47d1-568a-837f-8d8e06d3ea35)

The Philtre (#ulink_15757e77-47d1-568a-837f-8d8e06d3ea35)

AT DAWN A MULE-BORNE litter, escorted by two armed servants, entered the great porch of the Artois house in the Rue Mauconseil. Beatrice d’Hirson, niece of the Chancellor of Artois and lady-in-waiting to the Countess Mahaut, alighted from it. No one would have thought that this handsome dark-haired girl had travelled nearly a hundred miles since the day before. Her dress was hardly creased; her face with its high cheekbones was as smooth and fresh as if she had just awakened from sleep. Besides, she had slept part of the way under comfortable rugs, to the swinging of the litter. Beatrice d’Hirson, and it was rare in a woman of that period, had no fear of travelling by night; she saw in the dark like a cat and knew that she was under the protection of the devil. Long-legged and high-breasted, walking with steps that seemed slow because they were long and regular, she went straight to the Countess Mahaut, whom she found at breakfast.

‘It is done, Madam,’ said Beatrice, handing the Countess a little horn box.

‘Well, and how is my daughter Jeanne?’

‘The Countess of Poitiers is as well as can be expected, Madam; her life at Dourdan is not too harsh and her gentle disposition has won over her gaolers. Her complexion is clear and she has not grown too thin; she is sustained by hope and by your concern for her.’

‘What of her hair?’ the Countess asked.

‘It has only a year’s growth, Madam, and is not yet as long as a man’s; but it seems to be growing thicker than it was before.’

‘But is she presentable?’