По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

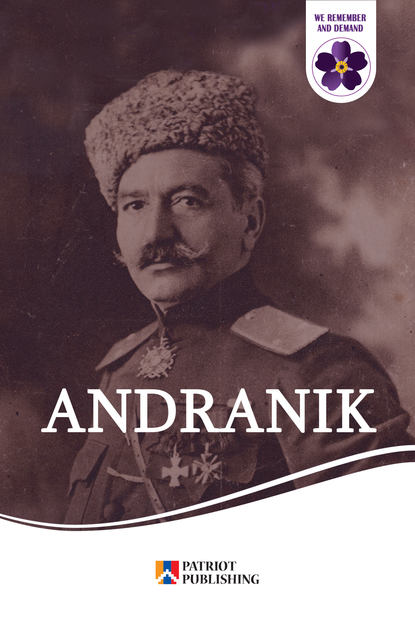

Andranik. Armenian Hero

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Since the Ottoman forces were effectively stopped at Sardarabad, the Armenian National Council declared the independence of the Russian Armenian lands on 28 May 1918. Andranik condemned this move and denounced the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. Angry with the Dashnaks, he favored good relations with Bolshevik Russia instead. Andranik refused to acknowledge the Republic of Armenia because according to the Treaty of Batum it "was only a dusty province without Turkish Armenia whose salvation Armenians had been seeking for 40 years." In early June, Andranik departed from Dilijan with thousands of refugees; they traveled through Yelenovka, Nor Bayazet and Daralagyaz, and arrived in Nakhichevan on 17 June.He subsequently tried to help the Armenian refugees from Van at Khoy, Iran. He sought to join the British forces in northern Iran, but after encountering a large number of Turkish soldiers he retreated to Nakhichevan. On 14 July 1918, he proclaimed Nakhichevan an integral part of Russia. His move was welcomed by Armenian Bolshevik Stepan Shahumyan and Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin.

Republic of Armenia delegation to the United States. Andranik is second from the bottom right.

Zangezur

Andranik with the commanders of the Special Striking Division in Zangezur, 1918

As the Turkish forces moved towards Nakhichevan, Andranik with his Armenian Special Striking Division moved to the mountainous region of Zangezur to set up a defense. By mid-1918, the relations between the Armenians and Azeris in Zangezur had deteriorated. Andranik arrived in Zangezur at a critical moment with around 30,000 refugees and an estimated force of between 3,000 and 5,000 men. He established effective control of the region by September. The role of Zangezur was crucial because it was a connection point between Turkey and Azerbaijan. Under Andranik, the region became one of the last centers of Armenian resistance after the Treaty of Batum.

Andranik's irregulars remained in Zangezur surrounded by Muslim villages that controlled the key routes connecting the different parts of Zangezur.According to Donald Bloxham, Andranik initiated the change of Zangezur into a solidly Armenian land by destroying Muslim villages and trying to ethnically homogenize key areas of the Armenian state. In late 1918, Azerbaijan accused Andranik of killing innocent Azerbaijani peasants in Zangezur and demanded that he withdraw Armenian units from the area. Antranig Chalabian wrote that, "Without the presence of General Andranik and his Special Striking Division, what is now the Zangezur district of Armenia would be party of Azerbaijan today. Without General Andranik and his men, only a miracle could have saved the sixty thousand Armenian inhabitants of the Zangezur district from complete annihilation by the Turko-Tatar forces in the fall of 1918"; he further stated that Andranik "did not massacre peaceful Tatars". Andranik's activities in Zangezur were protested by Ottoman general Halil Pasha, who threatened the Dashnak government with retaliation for Andranik's actions. Armenia's Prime Minister Hovhannes Katchaznouni said he had no control over Andranik and his forces.

Karabakh

Andranik with the Military Council of Goris, 1918

The Ottoman Empire was officially defeated in the First World War and the Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October 1918. The Ottoman forces evacuated Karabakh in November 1918 and by the end of October of that year, Andranik's forces were concentrated between Zangezur and Karabakh. Before moving towards Karabakh, Andranik made sure that the local Armenians would support him in fighting the Azeris. In mid-November 1918, he received letters from Karabakh Armenian officials asking him to postpone the offensive for 10 days ton allow negotiations with the Muslims of the region. According to Hovannisian, "the time lost proved crucial". In late November, Andranik's forces headed towards Shusha – the main city of Karabakh and a major Armenian cultural center. After an intense fight against the Kurds, his forces broke through Abdallyar and the surrounding villages.

By early December, Andranik was 40 km (25 mi) away from Shusha when he received a message from British General W. M. Thomson in Baku, suggesting that he retreat from Karabakh because the World War was over and any further Armenian military activity would adversely affect the solution of the Armenian question, which was soon to be considered by the 1919 peace conference in Paris.Trusting the British, Andranik returned to Zangezur.

The region was left under limited control of the Armenian Karabakh Council. The British mission under command of Thomson arrived in Karabakh in December 1918. Thomson insisted the council "act only in local, nonpolitical matters", which sparked discontent among the Armenians. An "ardent pan-Turkist" Khosrov bey Sultanov was soon appointed the governor of Karabakh and Zangezur by Thomson to "squash any unrest in the region". Christopher J. Walker wrote that "[Karabakh] with its large Armenian majority remained Azerbaijani throughout the pre-Soviet and Soviet period" because of "Andranik's trust of the word of a British officer".

Departure

Andranik with his men and two archbishops in Etchmiadzin just before leaving Armenia, April 1919

During the winter of 1918–19, Zangezur was isolated from Karabakh and Yerevan by snow. The refugees intensified the famine and epidemic conditions and gave way to inflation. In December 1918, Andranik withdrew from Karabakh to Goris. On his way, he met with British officers who suggested the Armenian units stay in Zangezur for the winter. Andranik agreed to such a proposal and on 23 December 1918, a group of Armenian leaders met in a conference and concluded that Zangezur could not cope with the influx of refugees until spring. They agreed that the first logical step in relieving the tension was the reparation of more than 15,000 refugees from Nakhichevan – the adjoining district that had been evacuated by the Ottoman armies. Andranik and the conference called upon the British to provide for the refugees in the interim. Major W. D. Gibbon arrived with limited supplies and money donated by the Armenians of Baku, but this was not enough to support the refugees.

Andranik Ozanian and Hovhannes Tumanyan in Tiflis

At the end of February 1919, Andranik was ready to leave Zangezur. Gibbon suggested Andranik and his soldiers leave by Baku-Tiflis railway at Yevlakh station. Andranik rejected this plan and on 22 March 1919, he left Goris and traveled across Sisian through deep snowdrifts to Daralagyaz, then moved to the Ararat plain with his few thousand irregulars. After a three-week march, his men and horses reached the railway station of Davalu. He was met by Dro, the Assistant Minister of Military Affairs and Sargis Manasian, the Assistant Minister of Internal Affairs, who offered to take him to visit Yerevan, but he rejected their invitation as he believed the Dashnak government had betrayed the Armenians and was responsible for the loss of his homeland and the annihilation of his people. Zangezur became more vulnerable to Azerbaijani threats after Andranik left the district. Earlier, before Andranik's and his soldiers' dismissal, the local Armenian forces had requested support from Yerevan.

On 13 April 1919, Andranik reached Etchmiadzin, the seat of Catholicos of All Armenians and the religious center of the Armenians, who helped the troops prepare for disbanding. His 5,000-strong division had dwindled to 1,350 soldiers. As a result of Andranik's disagreements with the Dashnak government and the diplomatic machinations of the British in the Caucasus, Andranik disbanded his division and handed his belongings and weapons to the Catholicos George V. On 27 April 1919, he left Etchmiadzin accompanied by 15 officers, and went to Tiflis on a special train; according to Blackwood, "news of his journey traveled before him. At every station crowds were waiting to get a glimpse of their national hero." He left Armenia for the last time; in Tiflis he met with Georgia's Foreign Minister Evgeni Gegechkori and discussed the Georgian–Armenian War with translation of Hovhannes Tumanyan.

Last years

Andranik Ozanian with General Jaques Bagratuni and Hovhannes Katchaznouni and Armenian military personnel in the United States, 1919

From 1919 to 1922, Andranik traveled around Europe and the United States seeking support for the Armenian refugees. He visited Paris and London, where he tried to persuade the Allied powers to occupy Turkish Armenia. In 1919, during his visit to France, Andranik was bestowed the title of Legion of Honor Officier by President Raymond Poincaré. In late 1919, Andranik led a delegation to the United States to lobby its support for a mandate for Armenia and fund-raising for the Armenian army. He was accompanied by General Jaques Bagratuni and Hovhannes Katchaznouni. In Fresno, he directed a campaign which raised US$500,000 for the relief of Armenian war refugees.

Andranik's wedding in Paris, 1922

When he returned to Europe, Andranik married Nevarte Kurkjian in Paris on 15 May 1922; Boghos Nubar was their best man. Andranik and Nevarte moved to the United States and settled in Fresno, California in 1922. In his 1936 short story, Antranik of Armenia, Armenian-American writer William Saroyan described Andranik's arrival. He wrote, "It looked as if all Armenians of California were at the Southern Pacific depot at the day he arrived." He said Andranik "was a man of about fifty in a neat Armenians suit of clothes. He was a little under six feet tall, very solid and very strong. He had an old-style Armenian mustache that was white. The expression of his face was both ferocious and kind." In his novel Call of the Plowmen (1979), Khachik Dashtents describes Andranik's life in Fresno; he changed Andranik's name to Shapinand:

After clashing with the leaders of the Araratian Republic and leaving Armenia, Shapinand settled in the city of Fresno, California. The basement of his house was converted into a hotel. His sword, the Mosin–Nagant rifle and his military uniform hung from the wall. This is also where he kept his horse, which he had brought to America on a steamship. Those weapons, that uniform, the grey papakhi, the black boots, and lion-like steed – this was the personal wealth he had come to possess throughout his life. His business no longer had to do with weapons. Shapinand spent his free time making small wooden chairs in his hotel. Many people, refusing to buy the quality American armchairs, bought his simple ones, some for use, others as souvenirs.

Death

Funeral of Andranik at the Ararat Cemetery in 1927

In February 1926, Andranik left Fresno to reside in San Francisco in an unsuccessful attempt to regain his health. According to his death certificate found in the Butte County, California records, Andranik died from angina on 31 August 1927 at Richardson Springs, California. On 7 September 1927, city-wide public attention was accorded to him for his funeral in the Ararat Cemetery, Fresno. The New York Times reported that more than 2,500 members of the Armenian community attended memorial services in Carnegie Hall, New York City.

Funeral of Andranik at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in 1928

He was initially buried at Ararat Cemetery in Fresno. After his first funeral, it was planned to take Andranik's remains to Armenia for final burial; however, when they arrived in France, the Soviet authorities refused permission to allow his remains to enter Soviet Armenia. Instead they remained in France and, after a second funeral service held in the Paris Armenian church, were buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris on 29 January 1928. In early 2000, the Armenian and French governments arranged the transfer of Andranik's body from Paris to Yerevan. Asbarez wrote that the transfer was initiated by Armenia's Prime Minister Vazgen Sargsyan. Andranik's body was moved to Armenia on 17 February 2000. It was placed in the Sport & Concert Complex in Yerevan for two days and was then taken to Etchmiadzin Cathedral, where Karekin II officiated the funeral service. Andranik was re-interred at Yerablur military cemetery in Yerevan on 20 February 2000, next to Vazgen Sargsyan. In his speech during the reburial ceremony, Armenia's President Robert Kocharyan described Andranik as "one of the greatest sons of the Armenian nation". Prime Minister Aram Sargsyan, Foreign Minister Vartan Oskanian, and one of Andranik's soldiers, 102-year-old Grigor Ghazarian, were also in attendance. A memorial was built on his grave with the phrase "Zoravar Hayots" – "General of the Armenians" – engraved on it.

Legacy and recognition

Public image

Andranik's memorial at Yerablur cemetery

Andranik was considered a hero during his lifetime. The Literary Digest, an influential American newspaper, described Andranik in 1920 as "the Armenian's Robin Hood, Garibaldi, and Washington, all in one". The same year, The Independent wrote that he is "worshiped by his countrymen for his heroic fighting in their defense against the Turks". In a letter to Andranik, the noted Armenian writer Hovhannes Tumanyan praised him, while Bolshevik and Soviet statesman of Armenian origin Anastas Mikoyan wrote in his memoirs that "the name Andranik was surrounded by halo of glory".

General Andranik on the cover of the French magazine L'Image, 1919

Andranik is considered a national hero by Armenians worldwide. He is also seen as a legendary figure in Armenian culture. Five surveys conducted by Gallup, Inc., International Republican Institute and the Armenian Sociological Association from 2006 to 2008 asked, "[o]f the prominent Armenian people and characters in Armenian history and folk culture, who is most suitable to be a national hero or leader at the present time?". Andranik was placed second after Vazgen Sargsyan; 9–18 % of the respondents giving Andranik's name. Andranik's activities have also attracted some criticism; for instance writer Ruben Angaladyan (hy) stated that Andranik "doesn't have the right" to have a statue in Yerevan, because he did not do "anything real" for the First Republic and he left Armenia. Angaladyan wrote that Andranik is a popular hero; however, he finds the term "national hero" in describing him unacceptable.

Andranik's grave in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris

Andranik is generally seen as a pro-Russian/Soviet figure. During the Soviet period, his legacy and those of other Armenian national heroes were diminished and "any reference to them would be dangerous since they represented the strive for independence", especially prior to the Khrushchev Thaw.Paruyr Sevak, a prominent Soviet Armenian author, wrote an essay about Andranik in 1963 after reading one of his soldier's notes. Sevak wrote that his generation knew "little about Andranik, almost nothing." He continued, "knowing nothing about Andranik means to know nothing about modern Armenian history."In 1965, Andranik's 100th anniversary was celebrated in Soviet Armenia.

Memorials

Statues and memorials of Andranik have been erected around the world, including in Bucharest, Romania (1936), Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris (1945), Melkonian Educational Institute, Nicosia, Cyprus (1990),Le Plessis-Robinson, Paris (2005), Varna, Bulgaria (2011),] and Armavir, Russia. A memorial exists in Richardson Springs, California, where Andranik died. In May 2011, a statue of Andranik was erected in Volonka village near Sochi, Russia; however, it was removed the same day, apparently under pressure from Turkey, which earlier announced that they would boycott the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics if the statue remained standing.

The first statue of Andranik in Armenia was erected in 1967 in the village of Ujan. More statues have been erected after Armenia's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991; three of which can be found in Malatia-Sebastia district (2000), near the St. Gregory Cathedral (by Ara Shiraz, 2002) and outside the Fedayi Movement Museum (2006) in the Armenian capital Yerevan. Also in Armenia, Andranik's statues stand in Voskevan and Navur villages of Tavush, in Gyumri's Victory Park (1994), Arteni, Angeghakot, and others.

An equestrian statue of Andranik near the Saint Gregory Cathedral in central Yerevan

Numerous streets and squares both inside and outside Armenia, including in Córdoba, Argentina, Plovdiv and Varna in Bulgaria, Meudon, Paris and a section of Connecticut Route 314 state highway running entirely within Wethersfield, Connecticut are named after Andranik. General Andranik Station of the Yerevan Metro was opened in 1989 as Hoktemberyan Station and was renamed for Andranik in 1992. In 1995, General Andranik's Museum was founded in Komitas Park of Yerevan, but was soon closed because the building was privatized. It was reopened on 16 September 2006, by Ilyich Beglarian as the Museum of Armenian Fedayi Movement, named after Andranik.

According to Patrick Wilson, during the Nagorno-Karabakh War Andranik "inspired a new generation of Armenians". A volunteer regiment from Masis named "General Andranik" operated in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh during the conflict.

Many organizations and groups in the Armenian diaspora are named after Andranik. On 11 September 2012, during the Bulgaria vs. Armenia football match in Sofia's Levski National Stadium, Armenian fans brought a giant poster with pictures of General Andranik and Armenian officer Gurgen Margaryan, who was murdered in 2004 by Azeri lieutenant Ramil Safarov. The text on the poster read, "Andranik's children are also heroes … The work will be done".

The manuscripts of General Andranik, 65 pages long and the only known memoir of General Andranik written by him, were returned to Armenia in May 2014. Andranik, while in the United Kingdom, had sent them to Paris in order to be published in 1921, from where they had been sent to Beirut in the 1960s for safe keeping until the Lebanese Civil War, then moved to Greece, and again back to England from where the manuscripts were finally sent to the National History Museum in Yerevan through Culture Minister Hasmik Poghosyan, almost a century after Andranik had parted with them.

In culture

A comic by Stookie Allen depicting Andranik, New York Journal-American, 1920

Andranik has been figured prominently in the Armenian literature, sometimes as a fictional character. The Western Armenian writer Siamanto wrote a poem entitled "Andranik", which was published in Geneva in 1905. The first book about Andranik was published during his lifetime. In 1920, Vahan Totovents, under the pen name Arsen Marmarian, published the book Gen. Andranik and his wars (Զոր. Անդրանիկ և իր պատերազմները) in the Entente-occupied Constantinople.The famed Armenian-American writer William Saroyan wrote a short story titled Antranik of Armenia, which was included in his collection of short stories Inhale and Exhale (1936). Another US-based Armenian writer Hamastegh's novel The White Horseman (Սպիտակ Ձիավորը, 1952) was based on Andranik and other fedayi. Hovhannes Shiraz, one of the most prominent Armenian poets of the 20th century, wrote at least two poems about Andranik; one in 1963 and another in 1967. The latter one, titled Statue to Andranik (Արձան Անդրանիկին), was published in 1991 after Shiraz's death. Sero Khanzadyan's novel Andranik was suppressed for years and was published in 1989 when the tight Soviet control over publications was relaxed. Between the 1960s and the 1980s, author Suren Sahakyan collected folk stories and completed a novel, "Story about Andranik" (Ասք Անդրանիկի մասին). It was first published in Yerevan in 2008.

Lord Kitchener Wants You-influenced poster depicting Andranik. The caption reads "Chase the holy dream of your people".

Andranik's name has been memorialized in numerous songs In 1913, Leon Trotsky described Andranik as "a hero of song and legend".Andranik is one of the main figures featured in Armenian patriotic songs, performed by Nersik Ispiryan, Harout Pamboukjian and others. There are dozens of songs dedicated to him, including Like an Eagle by gusan Sheram, 1904 and Andranik pasha by gusan Hayrik.Andranik also features in the popular song The Bravehearts of the Caucasus (Կովկասի քաջեր) and other pieces of Armenian patriotic folklore.

Several documentaries about Andranik have been produced; these include Andranik (1929) by Armena-Film in France, directed by Asho Shakhatuni, who also played the main role;General Andranik (1990) directed by Levon Mkrtchyan, narrated by Khoren Abrahamyan; and Andranik Ozanian, a 53-minute-long documentary by the Public Television of Armenia.