По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

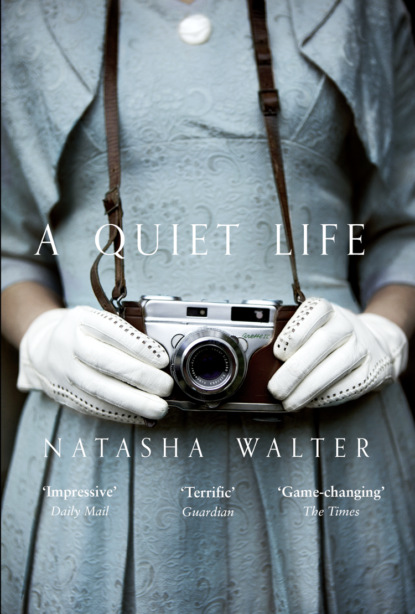

A Quiet Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It isn’t me, dear; it’s the way that the world is. Laura, we should really talk about this too … Polly’s last letter was definitely concerned, and I think she’s right, that we should think about booking you a passage back quite soon. There’s no hope of visiting the Continent while things are as they are, and I really think that—’

‘Just because we can’t go to France in the summer doesn’t mean that I have to give up my place at university.’

‘Do you mean you’d like me to go back?’ Laura was, to her surprise, horrified at the thought. Suddenly she realised how she had got used to the pleasures of this life – on the one hand, the comfortable round of shopping and gossip, social engagements and visits, in which the expectations on her were easy and undemanding; and on the other hand, all the time there was the possibility of her next meeting with Florence, the sporadic crossings into a world where the future was being made and her growing familiarity with their discussions of the new world to come. But her horror was silent, confined inside her head, while Winifred was openly furious, the words tumbling out of her.

‘I know, you say it’s the war coming, and before it was because of your chest pains, but don’t you see, Mother, it can’t always be about other things – it has to be about me too. I can’t stop living, I can’t just sit here my whole life because you sat at home all of yours …’

Laura stood at the table, unable to sit down, riveted by Winifred’s sudden honesty. How brave she seemed, in her green jersey, her hair pinned into curls in readiness for the evening’s party, arguing with her mother while coffee cooled in their cups. Laura was not surprised, however, when Dee said nothing at all in response. It was as though Winifred had not spoken, as she turned to Laura and asked if she would like a boiled egg with her toast. Even when Winifred stood up and, throwing down her napkin, stamped out of the room, Dee simply folded her lips together and told Laura she was probably over-excited about the evening. To her shame, Laura colluded in pretending that Winifred did not know what she was saying. She sat down and ate her breakfast, and listened to Aunt Dee talking about whether the gardener had been right to plant the lilies right up against the house like that – how would they get enough sunshine? Aunt Dee wondered.

After breakfast Laura went to find Winifred, who was sitting in the garden in the thin sunshine, pretending to read a book. She listened to Winifred’s complaints about her mother for a long while, and then reminded her that Dee had said it was time for Laura to go back. ‘I don’t want to,’ Laura said. ‘I really don’t want to.’

She wanted Winifred to say, I don’t want you to go either, but Winifred looked puzzled.

‘Don’t you? Is it about this man?’

‘I don’t know.’ Laura wished she could tell Winifred about Florence and all she meant to her, but she still held back. It would seem ridiculous now to confess that she had not been meeting some dashing man from the boat, and also she was afraid that Winifred would find Florence and Elsa and their politics absurd and would never understand the importance of what Florence had offered her. ‘Do you think I should go back?’

‘God knows. Mother thinks – like your mother I suppose – that it’s going to be 1914 and worse. Father was almost an old man, so he didn’t have to go, but the men they had danced with … I don’t have to explain, I’m sure you’ve heard enough stories from Aunt Polly.’

Laura could not tell her that her mother had never mentioned the war.

‘No wonder they married where they could – sorry, I’m sure your father is … it’s just Mother is such a snob, she thinks your mother only fell in with him because there wasn’t anyone left in England.’ Winifred turned to Laura, but she was unsmiling. ‘And this time – you know what they’re saying. Aerial bombs, all of that – but what are we supposed to do? We can’t stop the world.’

Just then Mrs Venn came into the garden, saying Giles was on the telephone for Winifred. ‘God, if he’s cancelling this evening, I tell you …’ and she stalked off.

But he was telephoning to ask if Laura could come with Winifred. Apparently the girlfriend of one of his friends was unwell, and so there was a gap for another woman at the dinner, and at the dance afterwards as well. Winifred accepted without even consulting her, and immediately she came off the telephone she called to Laura to come upstairs and look over what she would wear.

‘I suppose it is a bit of a winter dress, but it’s the right one,’ Winifred said eventually, after Laura had put on each of her two evening dresses and she had vetoed the grey one. ‘You don’t want to look like Jane Eyre,’ she said, and although Laura wasn’t sure of the reference, she could see that the dress she had thought of as silvery and subtle was in fact drab and drained her face of colour. Nobody could say that the red velvet dress was dull. Laura had bought it in Boston and had never worn it, but had been aware of it hanging up in the closet here in London, a brilliant rebuke to the dullness of most of her days. She wasn’t sure that she wanted to wear it. Looking at herself in the mirror, she could only see the dress, not herself, but Winifred was so certain that she gave it to Mrs Venn to be pressed.

After lunch Aunt Dee suggested that the girls should rest in their rooms before the evening’s outing. Winifred scorned the idea, and stayed reading in the living room, but Laura was thankful to be able to go upstairs. Lying on the big, high bed, she started re-reading old letters from her mother and Ellen. ‘I think you should book a passage for April,’ her mother had written. And now April was here. Laura laid the letters aside and wondered whether she was foolish to want to stay in London. It was true that nobody could ignore the sandbags on the streets and the trenches dug into the parks, not to mention the constant talk about what aerial warfare would be like and the Armageddon that would ensue. But despite the fatalistic talk, despite the physical reality of the city’s preparations, there was nothing concrete for Laura in the thought of war.

She looked into a drawer of the little desk where she had put the most recent pamphlet she had borrowed from Florence, Will It Be War?, which she had already started, but not finished. Its grand rhetoric, ‘Never, never will we bow the knee to fascism’, seemed too distant from her. Again she cast her mind back to the boat, and the moment when Florence painted for her a picture of what family and work might be like without false authority. That made sense to her; she felt it again, a taste of freedom, a world made in line with human desire. But the story of how they were all to fight as never before seemed dark to her, a summoning of something too large for her to comprehend. She found herself muttering some phrases from the pamphlet under her breath, as if she would commit them to memory to hold her to the right path.

Just then the handle of her door turned and Winifred came in, but to Laura’s relief she did not seem to notice her confusion as she shoved the pamphlet under her pillow. She had just come to suggest that Laura might want to start getting ready for the evening and that the bathroom was free. Shortly afterwards, lying in the warm water and looking down at her body, her skin greenish in the water that was reflecting the tiles around the bath, Laura felt a huge reluctance weighing her down. The little she had heard about Giles’s friends had not endeared her to the idea of meeting them.

Back in her room, she realised that the cherry-red velvet of the dress smelt of mothballs, as everything in this house did after a while. But it slithered with a cool touch over her breasts and legs as she pulled it on and zipped it tightly up the side. Lipsticking her mouth, looking for her pearl earrings, she was seeing herself only bit by bit in the mirror. Her lips – was the colour even? Her waist – did her garter belt show through the velvet? Her hair – should she push it behind her ears or fluff the curls forwards? But then, just as she was about to leave the room, she turned and saw her full reflection, as she had seen Winifred suddenly in the dressmaker’s, and was startled. It was such a complete picture, it was so finished. It was only for a second that she saw herself like that, and as soon as she walked out and Aunt Dee commented on her dress and asked her if she had a wrap, she lost the image completely. She was fragmented again; she had no idea how others saw her.

Giles was waiting for them in the living room, and she and Winifred followed him to his motor car, which was waiting outside. Laura had never seen London from a car before, and the city surprised her, rolling past the windows with a kind of emphatic repleteness, as if it were being unfurled particularly for them. Giles and Winifred talked in their usual sparring way in the front seats, but she was hardly listening and was surprised when finally the car stopped outside a terrace of vast white houses rising sheer into the dimming sky.

Once inside, Winifred introduced Laura to the man who she understood was her partner for the evening, whose girlfriend had been taken unwell. Tall, thickset, with a ruddy face and even, for all he was only Giles’s age, the suggestion of jowls.

‘Good of you to come out at such short notice,’ Quentin said to her. There was a note of condescension in his voice, clear enough for Laura to pick it out even in that room in which all the men seemed to speak with the same amused, arrogant tones. She was introduced to his father, who was a study in the fleshiness and loudness that Quentin himself was going to achieve, and to a Mrs Bertrand, a middle-aged woman with the most impressive black pearl necklace, who ignored Winifred and Laura and went on talking to the other two women who were already in the room.

Alongside Giles and Quentin was a young man who was bending to put a record on the gramophone. He introduced himself as soon as the needle started to whirl, and Laura realised that this was Alistair, the man who was partnering Winifred. He was the most engaging of the men, with elastic, exaggerated hand movements and round blue eyes that seemed to take in everything about the two girls. There was a generosity in that; to him, they did register, even if their presence was a matter of indifference to the others in the room. Behind him was an untidy, good-looking man who did not even bother to come forward to be introduced, but put his arm around Giles and started telling him what was obviously a racy story, judging by the way he lowered his voice as he came to the end of it.

Despite the presence of Quentin’s father and three other women, all the energy of the room came from the four young men, who seemed to be performing for one another, all talking at once, or almost, in quick, truncated sentences that would suddenly give way to protracted anecdotes, sustained as long as each could keep the floor. Laura had never been in such a relentlessly masculine atmosphere, she thought as they all moved to the dinner table. The women provided the colour between the black and white of the men’s tuxedos, but that was all they seemed to be there for; these flashes – green, scarlet, blush and blue – between the black coats.

Sitting at the dinner table as the first course was brought in, she thought she should say something to Quentin. ‘It’s your sister’s party we’re going to later?’

‘The redoubtable Sybil Last, indeed, her inevitable dance. Luckily, she has been persuaded away from providing entertainment for it in the style of last year … Do you remember, Alistair, the awfulness of the singers we were treated to then? The one good thing about the current situation is that no one thinks it’s appropriate to ship one’s entertainment over from France – too extravagant by far, not that that has ever put off dear Sybil … Do you remember, Giles …’ and another anecdote, interminable, emphatic, began to roll. Laura was careful to laugh in the right places, and that was as much as she could do.

Although later on Laura came to see each of them – Quentin, Giles, Alistair and Nick – as individuals, at this first meeting she could only see the set of friends as one cawing mass. She could not imagine feeling at ease with them and picked up her spoon almost in gratitude to have something to do. At the first taste of the soup, however, she found herself grimacing. It was a creamy, pale green soup, pretty in gilt-edged bowls, but maybe it had spent too long sitting in a warm kitchen. Something – the cream, the stock, the potatoes – had begun to turn, and a rotten taste filled her mouth. She laid her spoon down, as did others, but Quentin went on eating as if he had noticed nothing. Her unease grew as she realised how physically uncomfortable she was. She had only ever tried this dress on standing up, and now, sitting down, she was becoming increasingly aware that it was too tight for her, that the cut was too rigid over her ribs and that she had to keep her back ramrod-straight if it wasn’t to tear.

When the second course was brought in, she tried to speak for the second time, this time to Alistair, who was on her other side. ‘You all knew one another at university?’ she said, aware of what a lame gambit it was.

‘Knew each other – loved each other,’ he said with an exaggerated sigh. ‘And here we still are, together as ever. Giles the scientist, Nick the joker, myself the writer and Quentin – Quentin the arranger of festivities.’

‘What about Edward?’ Quentin boomed across Laura. ‘Just because he isn’t here, don’t forget Edward – what’s Edward?’

‘Edward, the philosopher – the absent philosopher.’

‘Why isn’t he here?’ asked Giles.

‘Have you only just thought to ask?’ said Quentin. ‘As a matter of fact, he’ll be at Sybil’s, but he said no to dinner … said he always has to work so late … said he couldn’t bear it … you know what Edward is like – the less …’ he waved his hand vaguely around the table, ‘the better.’ Not knowing Edward, Laura could not tell whether he meant the less female company, the less dinner, or the less gossip, but that was all right, since very little of the conversation made any sense to her at all. It was all about mutual friends, shared history and absurd tales of other social engagements.

All in all, Laura was relieved when the dinner came to an end and they set off for the dance. They were offered cars, but apparently the other house was only a few minutes away, and everyone exclaimed that they would rather walk. The other women had fur wraps, but Laura was glad, stepping down to the sidewalk, to feel the air on her bare arms. The scene, as they turned into a neighbouring square, seemed familiar, and suddenly Laura was thrown back in her memory: shouts of struggle, the police, women with their pots of paint and slogans. This was the very place she had come to during her first week in London, on that extraordinary protest. There was Halifax’s house. They passed it, and went on walking to another square, another row of white houses, and as they walked up the steps of one, the door was opened by a manservant. Beyond him was a wide hall painted turquoise, opening into rooms where lamps were reflected from mirror to mirror.

Here, Quentin’s father and Mrs Bertrand moved on and into the party, but their group took up a place in the first room, and once they had been supplied with champagne, the chatter went on much as it had done over dinner, the women providing simply an audience for the gestures and conversation of the men. All except Winifred, who, Laura was rather impressed to note, seemed to be enjoying swapping stories with Alistair. Alistair was the only one of the men who appeared to imply, by his voice and reactions, that the presence of the women enhanced the evening for him, and he was egging Winifred on to talk about Giles as a boy. More and more little groups came into the room, full of expectant faces, but their group stayed together and few people came to greet them. Then Laura saw a tall, light-haired man walk in and scan the room.

‘Edward! You made it,’ It was Quentin’s booming voice, calling the new arrival into the circle. ‘Why haven’t we seen you for so long? Has the Foreign Office been working you to the bone?’ The men shifted to allow Edward to join them.

‘Have you met our new friend?’ Quentin said, as Edward shook hands with each of the group. ‘Laura Leverett – Giles’s cousin – American heiress from Washington.’

Edward nodded, his light gaze passing over her. ‘Where is Sybil?’

The men looked around, and Alistair gestured to the other side of the room, where most of the guests seemed to be congregating.

‘Don’t rush off,’ Quentin said. ‘You haven’t told us anything, and we do need the inside track – now more than ever. What did Halifax mean yesterday? Is he really trying to charm Germany again?’

The group seemed to hesitate as they waited for Edward’s response. He paused to flick ash from his cigarette onto a silver ashtray on a mantelpiece, and then said, ‘He’s always wanted to avoid war …’

‘But cosying up now …’

‘Cosying?’

‘You see him every day, how would you describe it?’

Quentin seemed irritated with his friend, leaning towards him and frowning, but Edward was unresponsive, his head tilted back.

Alistair burst in. ‘If he was trying to negotiate a treaty, would the British public stand for it now?’

‘The great British public would welcome anything that let them off a fight, wouldn’t they?’ Nick gestured at someone for more drinks. As the servant came forward, breaking up the group as glasses were filled, Laura turned to Edward.

‘I’m not from Washington,’ she said, ‘and I’m not an heiress.’

‘But your name is Laura?’

She nodded.