По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

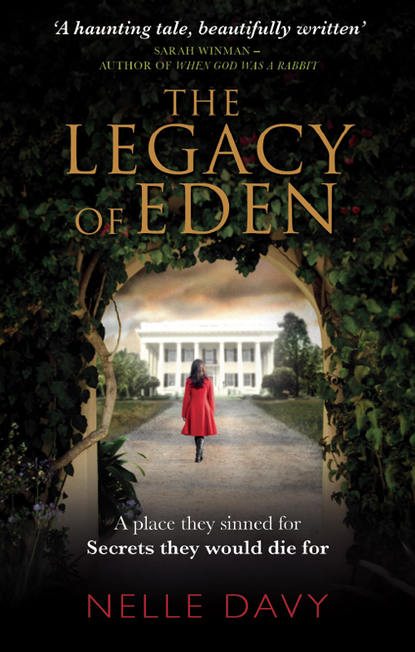

The Legacy of Eden

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Where?” asked Anne-Marie.

“Aurelia, their farm. We’re invited.”

“Oh,” said Anne. “Why?”

“To celebrate Cal coming home.”

“That’s nice,” she said halfheartedly.

“Leo won’t think so,” her husband muttered in reply, before turning back to read his paper. And so, because he was preoccupied, she didn’t bother to question him, and as usual they finished the remainder of their dinner in silence.

Two weeks later and my grandmother stepped foot on Aurelia for the first time. The place as it was then would be unrecognizable to me: no sign in curlicue lettering, no pockets of flowers, no white house. I have seen pictures of what it used to be like. Instead of the daisies and hyacinths, the entrance to the farm was simply a sandy drive that wove its way along the crab grass. The house on the mound was not white and tall, but gray and flat with dark shutters and a roof that peeked over the front in a slanted fringe. In the distance the grass swept on and on, periodically knotted with thatches of prairie grass until eventually it found the fields of corn and the stream. It was large and expansive and Anne-Marie’s first thought when she saw all of this was that it was ugly.

Did she see everything then that it could be? Did she re-envision the sight before her and see in her mind the potential that could arise from beneath her guiding hand? It would not have surprised us if she had. In fact in some ways it is what we would have expected from her, because in the end the way she knew exactly how to mold the farm to suit her tastes and bring out the beauty in it was almost prophetic. She was so intuitive that we all assumed she must have connected to it from the first. But in truth there was no such feeling. Maybe Lavinia Hathaway would come to feel that way, but in 1946, Anne-Marie Parks did not. Instead, she did not like Aurelia and she hated the idea of going to the party.

It was not the first time this had happened. Her insides had a habit of withering in anxiety whenever she was faced with an event like this. The farm at this point was not the great estate it would come to be in my lifetime, but it was still considered to be a prosperous holding and the Hathaways were a very respected family in the community. Nobody would have missed the party if they could help it and the weight of expectation that was implicit in the invite weighed down on Anne-Marie from the moment her husband had mentioned it to her over dinner. Because no matter what she wore or how many hours she spent on her hair and makeup, she always felt like the unwanted niece of her lawyer uncle, the abandoned child, a product of other people’s charity.

It was as if she had been branded and nothing could remove it. Not seducing and marrying the town doctor; not moving into a house of her own, which was only slightly smaller than her uncle’s. Often she would wonder if this was to be it. If she would live and die as nothing more than the doctor’s wife and her uncle’s former charge. She would think these things as she cooked, or ran her errands, and she would suddenly be consumed with an urge to utterly annihilate everything around her. Once she took the kitchen knife to the soft pink curtains that hung over the window above the sink. She slashed at them, not caring where she plunged the knife, thrusting so deeply that the point scraped against the glass, leaving long thin scratches on the pane. She eventually stopped, the energy just draining from her, but once it was over she hadn’t felt contrite or ashamed. She bundled up the material, composed an excuse for her husband and ordered some new curtains from a magazine she subscribed to. Why she felt like this she did not know. It seemed to her she had always been this way: always bitter and resentful because she did not count, and even now she did not know how to change this.

As she climbed the mound to the house, which was already strewn with lights, she began to prepare herself for the night ahead. She knew it annoyed her husband that she couldn’t interact with their neighbors. He had known about the comments and gossip that started after their engagement had been announced, but only from a distance. To his face, at least, it was clear that all the men were secretly envious that he had managed to entrance a pretty nineteen-year-old. He did not know that the women had labeled his wife a harlot and a temptress; that despite the respectability of his name, to them she was still no better than his whore. Nor did he ever guess at how they stared at her belly after the first six months and noted with pursed lips and inward smiles that it had continued to stay flat. He did not sense their distaste, he only saw her isolation, an isolation he believed was self-imposed. That was why he left her at gatherings. After a few weeks into their marriage, he told her that if he stayed with her, she would never force herself to socialize. He chose not to acknowledge that whether he was with her or not, it made no difference.

So when they reached the door and were shown through to the garden, he immediately detached himself, leaving her standing on the back porch, cradling the flowers she had brought and staring at the islands of people knotted among the expanse of green punctured by white-clothed tables and multicolored streamers of silver, turquoise and gold.

She moved through these islands like a navigator through treacherous waters, slipping between the gaps she could find until she reached a small clearing that had not yet been invaded. She did not even try to see where her husband had gone. She came near one of the long tables covered with steaming hams and bowls of salad and rested the flowers near the paper cups and the punch bowl. Nearby stood a group of huddled men, whom she ignored. Instead she served herself a drink, and as she picked over the food she began to wonder how she would be able to get through the evening without taking a knife to something.

“Must just eat you up, Leo,” one of the men near her said.

“He’ll be gone soon, we all know he won’t stay.”

“What was he doing up in Oregon anyway?”

“Salesman.”

“Walter knows he ain’t no farmer. Blood or no blood he’s seen you sweat over this place and he won’t do anything that ain’t in the interests of the farm. Ain’t no salesman can farm.”

“Yeah, but he did use to farm here, didn’t he?”

“That was a long time ago, though.”

“To be sure.”

“You’re the one who’s been here. No one cares about that firstborn stuff. It’s about what you done, not what position you were born into.”

“I hope he knows that.”

“He’s a shrewd man, your pa.”

“Yeah and a sick one. Sick ones stop being shrewd and start getting sentimental.”

“Not when it comes to money they don’t.”

“And besides, if your pa does start to feel sentimental all’s he got to do is start remembering why he sent him away in the first place.”

“Come on now, Dan, everyone knows that were an accident.”

“I don’t want to talk about that.”

“No … sure, Leo, of course. We meant no disrespect.”

“Why, Anne-Marie, don’t you look fetching?”

Anne-Marie turned to see her cousin, the girl she had grown up with, standing before her, a broad smile drawing a hole in her wide, pink flushed face.

“Thank you, Louise,” she replied calmly, though she turned away briefly and slowly closed and reopened her eyes. She had not spoken with her cousin in weeks but each time she did it drained her. It ate up all her reserves to keep a neutral expression on both her tongue and her face, when secretly she wished God would just grant her lifelong wish and snap the girl’s neck like a twig.

“So thin, though, Anne-Marie, if people were to look at you they’d think we were still in the Depression. You know I think you’ve lost weight again. You been losing it steadily ever since you left home, but I guess that’s what happens when you have to cook for yourself. I noticed Lou is thinner than he was, too. Maybe you should talk him into hiring you a housekeeper, if he can afford it on a local doctor’s wage.”

“I wouldn’t know. I don’t question him about his finances.” Anne-Marie turned to her plate. Louise cackled in laughter and put a hand on her shoulder.

“My God, what wife doesn’t know how much she can push her husband for? You are a funny one. The very least he can do is get you some Negro girl in the place, preferably one from down south somewhere. They don’t haggle as much as the ones up here. I insist you try, any more weight loss and people will start thinking something’s wrong with you.”

“I’m just fine,” snapped Anne-Marie as her jaw ached under the strain.

“But maybe not,” said Louise, cocking her head to her side and fingering the hem of Anne-Marie’s dress. “Maybe the dress just makes it seem that way. Boy, you can do anything with a sewing machine,” she said, dropping her hand away and smoothing down the cream silk that fell across her own waist and flared out at her hips. Suddenly she laughed. “Remember all those times I’d come home and find you just sewing away, always mending, always poring over your clothes and stuff. Why you didn’t just ask Daddy to buy you something new I could never understand.”

Anne-Marie stared at her cousin. She saw her cock her head to her side and gaze at her as if she were waiting for something, always waiting for something, and then finally smiling as she used to when she saw that Anne-Marie could not think of a way to respond.

“Daddy said you used to get that from your mother, that thriftiness.” She bent nearer to her at this point. “Truth be told, I think he was glad that’s all you got.”

Anne-Marie cleared her throat and tried to turn away. Louise stepped back and frowned.

“Sorry, I forgot how you never mention your mother.”

And she never did—never. I remember my father saying how he had asked about her once. My grandmother had gotten up from her chair and left the room without saying a word, and when he had asked his father why she was that way, all my grandfather could say was, “Some things just run through you so deep, all they leave is a hole.”

And so it was with my grandmother, so that she became little more than a void in the disguise of a woman.

But while Anne-Marie may have refused to talk about her mother, almost everybody else did. They couldn’t help themselves after her uncle’s wife, a rotund woman who had an unfortunate partiality to loudly colored prints, had taken every opportunity at the store or in the street, to explain to her neighbors how her sister-in-law had turned up on their doorstep with a carpet bag, a spaniel puppy and a seven-year-old girl in a blue gingham pinafore.

Soon everyone would come to know that Eleanor Brown had left her husband, a teacher in San Diego, to come back to her home town. The rumor was that he had run up debts and their house was to be sold, though people suspected there were far more shameful indiscretions than these two meager facts. No one said so directly, but everyone knew they would divorce. People, including her own family, had assumed that Eleanor would stay in town under the supervision and support of her brother and create a new life, but it was not to be. In the early hours of a Wednesday morning, three weeks after she arrived, her brother came down to his morning coffee to find that not only had it not been made, but his wife also sat at their table, her head in her hands with a note laid open before her. While brief, Eleanor was certainly direct. The child was to stay with them until she could find a job and a home elsewhere. She left no forwarding address in case they chose to forward her daughter to her as well as her mail. So they were left with this little girl from San Diego whom they had only ever met once before and who was now to be staying with them for heaven knew how long.

At first Eleanor decided to keep up the pretense of parenthood and send them money every month. The amount always varied. Then after two years she sent forty dollars and a wedding photograph of her and her new husband. Her sister-in-law had humphed at this.

“At least she’s not wearing white,” she had said.

That was the last they had ever heard of her.

It was after this that they changed my grandmother’s name. Her aunt had never liked it. She had thought it pretentious, flighty: in short, far too reminiscent of the traits inherent in her wayward mother. So they had taken it away and instead settled her with her middle name Anne, though they thought Anne Brown was far too dour so they had given her Marie as well. They had thought in doing so they were being kind.