По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

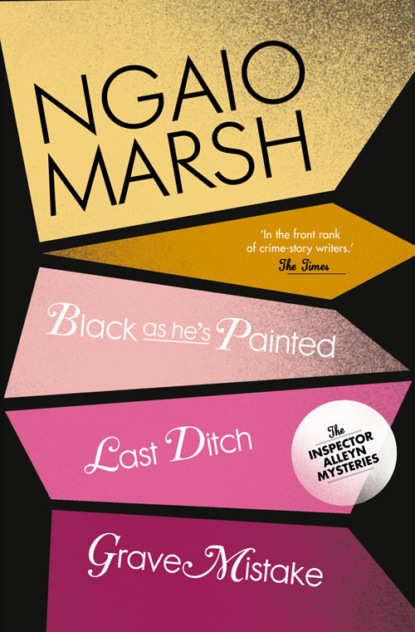

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 10: Last Ditch, Black As He’s Painted, Grave Mistake

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I reminded The Boomer of that incident.’

Mr Whipplestone said archly to Troy: ‘Y’ou know, he’s much more fully informed than I am. What’s he up to?’

‘I can’t imagine, but do go on. I, at least, know nothing.’

‘Well. Among these African enemies, of course, are the extremists who disliked his early moderation and especially his refusal at the outset to sack all his European advisers and officials in one fell swoop. So you get pockets of anti-white terrorists who campaigned for independence but are now prepared to face about and destroy the government they helped to create. Their followers are an unknown quantity but undoubtedly numerous. But you know all this, my dear fellow.’

‘He’s sacking more and more whites now, though, isn’t he? However unwillingly?’

‘He’s been forced to do so by the extreme elements.’

‘So,’ Alleyn said, ‘the familiar, perhaps the inevitable, pattern emerges. The nationalization of all foreign enterprise and the appropriation of properties held by European and Asian colonists. Among whom we find the bitterest possible resentment.’

‘Indeed. And with some reason. Many of them have been ruined. Among the older groups the effect has been completely disastrous. Their entire way of life has disintegrated and they are totally unfitted for any other.’ Mr Whipplestone rubbed his nose. ‘I must say,’ he added, ‘however improperly, that some of them are not likeable individuals.’

Troy asked: ‘Why’s he coming here? The Boomer, I mean?’

‘Ostensibly, to discuss with Whitehall his country’s needs for development.’

‘And Whitehall,’ Alleyn said, ‘professes its high delight while the Special Branch turns green with forebodings.’

“Mr Whipplestone, you said “ostensibly”,’ Troy pointed out.

‘Did I, Mrs Rory? – Yes. Yes, well it has been rumoured through tolerably reliable sources that the President hopes to negotiate with rival groups to take over the oil and copper resources from the dispossessed who have, of course, developed them at enormous cost.’

‘Here we go again!’ said Alleyn.

‘I don’t suggest,’ Mr Whipplestone mildly added, ‘that Lord Karnley or Sir Julian Raphael or any of their associates are likely to instigate a lethal assault upon the President.’

‘Good!’

‘But of course behind those august personages is a host of embittered shareholders, executives and employees.’

‘Among whom might be found the odd cloak-and-dagger merchant. And apart from all these more or less motivated persons,’ Alleyn said, ‘there are the ones policemen like least: the fanatics. The haters of black pigmentation, the lonely woman who dreams about a black rapist, the man who builds Anti-Christ in a black image or who reads a threat to his livelihood in every black neighbour. Or for whom the commonplace phrases – “black outlook, black record, as black as it’s painted, black villainy, the black man will get you” and all the rest of them, have an absolute reference. Black is bad. Finish.’

‘And the Black Power lot,’ Troy said, ‘are doing as much for “white”, aren’t they? The war of the images.’

Mr Whipplestone made a not too uncomfortable little groaning noise and returned to his port.

‘I wonder,’ Alleyn said, ‘I do wonder, how much of that absolute antagonism the old Boomer nurses in his sooty bosom.’

‘None for you, anyway,’ Troy said, and when he didn’t answer, ‘surely?’

‘My dear Alleyn, I understood he professes the utmost camaraderie.’

‘Oh, yes! Yes, he does. He lays it on with a trowel. Do you know, I’d be awfully sorry to think the trowel-work overlaid an inimical understructure. Silly, isn’t it?’

‘It is the greatest mistake,’ Mr Whipplestone pronounced, to make assumptions about relationships that are not clearly defined.’

‘And what relationship is ever that?’

‘Well! Perhaps not. We do what we can with treaties and agreements, but perhaps not.’

‘He did try,’ Alleyn said. ‘He did in the first instance try to set up some kind of multi-racial community. He thought it would work.’

‘Did you discuss that?’ Troy asked.

‘Not a word. It wouldn’t have done. My job was too tricky. Do you know, I got the impression that at least part of his exuberant welcome was inspired by a – well, by a wish to compensate for the ongoings of the new regime.’

‘It might be so,’ Mr Whipplestone conceded. ‘Who can say?’

Alleyn took a folded paper from his breast pocket.

‘The Special Branch has given me a list of commercial and professional firms and individuals to be kicked out of Ng’ombwana, with notes on anything in their history that might look at all suspicious.’ He glanced at the paper.

‘Does the same Sanskrit mean anything at all to you?’ he asked. ‘X. and K. Sanskrit to be exact. My dear man, what is the matter?’

Mr Whipplestone had shouted inarticulately, laid down his glass, clapped his hands and slapped his forehead.

‘Eureka!’ he cried stylishly. ‘I have it! At last. At last!’

‘Jolly for you,’ said Alleyn, ‘I’m delighted to hear it. What had escaped you?’

‘“Sanskrit, Importing and Trading Company, Ng’ombwana”.’

‘That’s it. Or was it.’

‘In Edward VIIth Avenue.’

‘Certainly, I saw it there: only they call it something else now. And Sanskrit has been kicked out. Why are you so excited?’

‘Because I saw him last night.’

‘You did!’

‘Well, it must have been. They are as alike as two disgusting pins.’

‘They?’ Alleyn repeated, gazing at his wife who briefly crossed her eyes at him.

‘How could I have forgotten!’ exclaimed Mr Whipplestone rhetorically. ‘I passed those premises every day of my time in Ng’ombwana.’

‘I clearly see that I mustn’t interrupt you.’

‘My dear Mrs Roderick, my dear Roderick, do please forgive me,’ begged Mr Whipplestone, turning pink. ‘I must explain myself: too gauche and peculiar. But you see –’

And explain himself he did, pig-pottery and all, with the precision that had eluded him at the first disclosure. ‘Admit,’ he cried when he had finished, ‘it is a singular coincidence, now isn’t it?’

‘It’s all of that,’ Alleyn said. ‘Would you like to hear what the Special Branch have got to say about the man – K. Sanskrit?’