По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

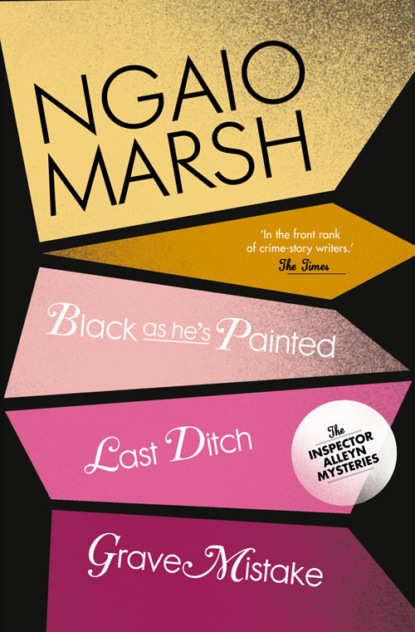

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 10: Last Ditch, Black As He’s Painted, Grave Mistake

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Superintendent Gibson muttered, ‘They’ve done it!’

‘Not precisely,’ Alleyn said. He stood up and at once the group of men moved further back. And there was The Boomer, bolt upright in the chair that was not quite a throne, breathing deeply and looking straight before him.

‘It’s the Ambassador,’ Alleyn said.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_1940c61f-de01-5114-adb9-205ff0b32624)

Aftermath (#ulink_1940c61f-de01-5114-adb9-205ff0b32624)

The handling of the affair at the Ng’ombwanan Embassy was to become a classic in the annals of police procedure. Gibson, under the hard drive of a muffled fury, and with Alleyn’s co-operation, had, within minutes, transformed the scene into one that resembled a sort of high-toned drafting-yard. The speed with which this was accomplished was remarkable.

The guests, marshalled into the ballroom, were, as Gibson afterwards put it, ‘processed’ through the dining-room. There they were shepherded up to a trestle table upon which the elaborate confections of Costard et Cie had been shoved aside to make room for six officers, summoned from Scotland Yard. These men sat with copies of the guest-list before them and with regulation tact checked off names and addresses.

Most of the guests were then encouraged to leave by a side door, a general signal having been sent out for their transport. A small group were asked, very civilly, to remain.

As Troy approached the table she saw that among the Yard officers Inspector Fox, Alleyn’s constant associate, sat at the end of the row, his left ear intermittently tickled by the tail of an elaborately presented cold pheasant. When he looked over the top of his elderly spectacles and saw her, he was momentarily transfixed. She leant down. ‘Yes, Br’er Fox, me,’ she murmured, ‘Mrs R. Alleyn, 48 Regency Close, SW3.’

‘Fancy!’ said Mr Fox to his list. ‘What about getting home?’ he mumbled. ‘All right?’

‘Perfectly. Hired car. Someone’s ringing them. Rory’s fixed it.’

Mr Fox ticked off the name, ‘Thank you, madam,’ he said aloud. ‘We won’t keep you,’ and so Troy went home, and not until she got there was she to realize how very churned up she had become.

The curtained pavilion had been closed and police constables posted outside. It was lit inside and glowed like some scarlet and white striped bauble in the dark garden. Distorted shadows moved, swelled and vanished across its walls. Specialists were busy within.

In a small room normally used by the controller of the household as an office, Alleyn and Gibson attempted to get some sort of sense out of Mrs Cockburn-Montfort.

She had left off screaming but had the air of being liable to start up again at the least provocation. Her face was streaked with mascara, her mouth hung open and she pulled incessantly at her lower lip. Beside her stood her husband, the Colonel, holding, incongruously, a bottle of smelling salts.

Three women in lavender dresses with caps and stylish aprons sat in a row against the wall as if waiting to make an entrance in unison for some soubrettish turn. The largest of them was a police sergeant.

Behind the desk a male uniformed sergeant took notes and upon it sat Alleyn, facing Mrs Cockburn-Montfort. Gibson stood to one side, holding on to the lower half of his face as if it was his temper and had to be stifled.

Alleyn said: ‘Mrs Cockburn-Montfort, we are all very sorry indeed to badger you like this but it really is a most urgent matter. Now. I’m going to repeat, as well as I can, what I think you have been telling us and if I go wrong please, please stop me and say so. Will you?’

‘Come on, Chrissy old girl,’ urged her husband. ‘Stiff upper lip. It’s all over now. Here!’ He offered the smelling salts but was flapped away.

‘You,’ Alleyn said, ‘were in the ladies’ cloakroom. You had gone there during the general exodus of the guests from the ballroom and were to rejoin your husband for the concert in the garden. There were no other guests in the cloakroom but these ladies, the cloakroom attendants, were there? Right? Good. Now. You had had occasion to use one of the four lavatories, the second from the left. You were still there when the lights went out. So far, then, have we got it right?’

She nodded rolling her gaze from Alleyn to her husband.

‘Now the next bit. As clearly as you can, won’t you? What happened immediately after the lights went out?’

‘I couldn’t think what had happened. I mean why? I’ve told you. I really do think,’ said Mrs Cockburn-Montfort squeezing out her voice like toothpaste, ‘that I might be let off. I’ve been hideously shocked, I thought I was going to be killed. Truly. Hughie –?’

‘Pull yourself together, Chrissy, for God’s sake. Nobody’s killed you. Get on with it. Sooner said, sooner we’ll be shot of it.’

‘You’re so hard,’ she whimpered. And to Alleyn: ‘Isn’t he? Isn’t he hard?’

But after a little further persuasion she did get on with it.

‘I was still there,’ she said. ‘In the loo. Honestly! – Too awkward. And all the lights had gone out but there was a kind of glow outside those slatted sort of windows. And I suppose it was something to do with the performance. You know. That drumming and some sort of dance. I knew you’d be cross, Hughie, waiting for me out there and the concert started and all that but one can’t help these things, can one?’

‘All right. We all know something had upset you.’

‘Yes, well, they finished – the dancing and drums had finished – and – and so had I and I was nearly going when the door burst open and hit me. Hard. On – on the back. And he took hold of me. By the arm. Brutally. And threw me out. I’m bruised and shaken and suffering from shock and you keep me here. He threw me so violently that I fell. In the cloakroom. It was much darker there than in the loo. Almost pitch dark. And I lay there. And outside, I could hear clapping and after that there was music and a voice. I suppose it was wonderful but to me, lying there, hurt and shocked, it was like a lost soul.’

‘Go on, please.’

‘And then there was that ghastly shot. Close. Shattering, in the loo. And the next thing – straight after that – he burst out and kicked me.’

‘Kicked you! You mean deliberately –?’

‘He fell over me,’ said Mrs Cockburn-Montfort. ‘Almost fell, and in so doing kicked me. And I thought now he’s going to shoot me. So of course I screamed. And screamed.’

‘Yes?’

‘And he bolted.’

‘And then?’

‘Well, then there were those three.’ She indicated the attendants. ‘Milling about in the dark and kicking me too. By accident, of course.’

The three ladies stirred in their seats.

‘Where had they come from?’

‘How should I know! Well, anyway, I do know because I heard the doors bang. They’d been in the other three loos.’

‘All of them?’

Alleyn looked at his sergeant. She stood up. ‘Well?’ he asked.

‘To try and see Karbo, sir,’ she said, scarlet-faced. ‘He was just outside. Singing.’

‘Standing on the seats, I suppose, the lot of you.’

‘Sir.’

‘I’ll see you later. Sit down.’

‘Sir.’

‘Now, Mrs Cockburn-Montfort, what happened next?’

Someone, it appeared, had had a torch, and by its light they had hauled Mrs Cockburn-Montfort to her feet.

‘Was this you?’ Alleyn asked the sergeant, who said it was. Mrs Cockburn-Montfort had continued to yell. There was a great commotion going on in the garden and other parts of the house. And then all the lights went on. ‘And that girl,’ she said, pointing at the sergeant, ‘that one. There. Do you know what she did?’