По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

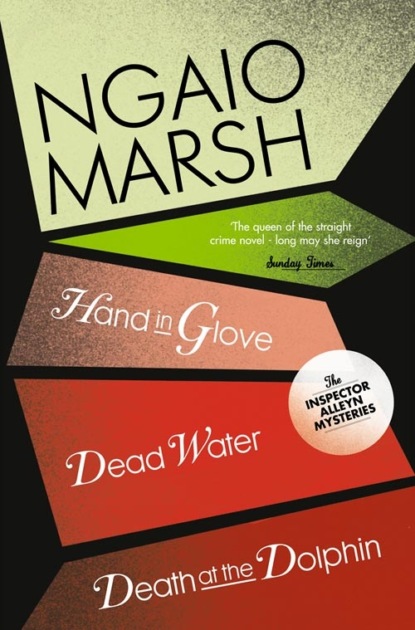

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 8: Death at the Dolphin, Hand in Glove, Dead Water

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Damn!’ Connie thought. ‘I forgot to tell her not to disturb either of them.’

Then the full realization of all the horrors of the preceding evening came upon her.

She was not an imaginative woman, but it hadn’t taken much imagination after her brother’s visit to envisage what would happen to Moppett if Mr Period’s cigarette-case was not discovered. Connie had tried to tackle Moppett and, as usual, had got nowhere at all. Moppett had merely remarked that P.P. and Mr Cartell had dirty minds. When Connie had broached the topic of Leonard Leiss and his reputation, Moppett had reminded her of Leonard’s unhappy background and of how she, Moppett, was pledged to redeem him. She had assured Connie, with tears in her eyes and a great many caresses, that Leonard was indeed on the upward path. If Connie herself had had any experience at all of the Leiss milieu and any real inclination to cope with it, she might possibly have been able to bring a salutary point of view to bear on the situation. She might, it is not too preposterous to suppose, have been able to direct Moppett towards a different pattern of behaviour. But she had no experience and no real inclination. She only doted upon Moppett with the whole force of her unimaginative and uninformed being. She was in a foreign country and like many another woman of her class and kind, behaved stupidly, as a foreigner.

So she bathed and dressed and went down to breakfast in a sort of fog and ate large quantities of eggs, bacon and kidneys indifferently presented by her Austrian maid. She was still at her breakfast when she saw Alfred, in his alpaca jacket and the cloth cap he assumed for such occasions, crossing the green with an envelope in his hand.

In a moment he appeared before her.

‘I beg pardon, miss,’ Alfred said, laying the envelope on the table, ‘for disturbing you, but Mr Period asked me to deliver this. No answer is required, I understand.’ She thanked him and when he had withdrawn, opened the letter.

Silent minutes passed. Connie read and re-read the letter. Incredulity followed bewilderment and was replaced in turn by alarm. A feeling of horrid unreality possessed her and again she read the letter.

My dear: What can I say? Only that you have lost a devoted brother and I a very dear friend. I know so well, believe me so very well, what a grievous shock this has been for you and how bravely you will have taken it. If it is not an impertinence in an old fogey to do so, may I offer you these very simple lines written by my dear and so Victorian Duchess of Rampton? They are none the worse, I hope, for their unblushing sentimentality.

So must it be, dear heart, I’ll not repine,

For while I live the Memory is Mine.

I should like to think that we know each other well enough for you to believe me when I say that I hope you won’t dream of answering this all-too-inadequate attempt to tell you how sorry I am.

Yours sincerely,

Percival Pyke Period

The Austrian maid came in and found Connie still gazing at this letter.

‘Trudi,’ she said with an effort, ‘I’ve had a shock.’

‘Bitte?’

‘It doesn’t matter. I’m going out. I won’t be long.’

And she went out. She crossed the green and tramped up Mr Pyke Period’s drive to his front door.

The workmen were assembled in Green Lane.

Alfred opened the front door to her.

‘Alfred,’ she said, ‘what’s happened?’

‘Happened, miss?’

‘My brother. Is he –?’

‘Mr Cartell is not up yet, miss.’

She looked at him as if he had addressed her in an incomprehensible jargon.

‘He’s later than usual, miss,’ Alfred said. ‘Did you wish to speak to him?’

‘Hall-o. Connie! Good morning to you.’

It was Mr Pyke Period, as fresh as paint, but perhaps not quite as rubicund as usual. His manner was over-effusive.

Connie said: ‘P.P., for God’s sake what is all this? Your letter?’

Mr Period glanced at Alfred, who withdrew. He then, after a moment’s hesitation, took Connie’s hand in both of his.

‘Now, now!’ he said. ‘You mustn’t let this upset you, my dear.’

‘Are you mad!’

‘Connie!’ he faintly ejaculated. ‘What do you mean? Do you – do you know?’

‘I must sit down. I don’t feel well.’

She did so. Mr Period, his fingers to his lips, eyed her with dismay. He was about to speak when a shrill female ejaculation broke out in the direction of the servants’ quarters. It was followed by the rumble of men’s voices. Alfred reappeared, very white in the face.

‘Good God!’ Mr Period said. ‘What now?’

Alfred, standing behind Connie Cartell, looked his employer in the eyes and said: ‘May I speak to you, sir?’ He made a slight warning gesture and opened the library door.

‘Forgive me, Connie. I won’t be a moment.’

Mr Period went into the library followed by Alfred, who shut the door.

‘Merciful heavens, Alfred, what’s the matter with you! Why do you look at me like that?’

‘Mr Cartell, sir,’ Alfred moistened his lips. ‘I, really, I scarcely know how to put it, sir. He’s, he’s –’

‘What are you trying to tell me? What’s happened?’

‘There’s been an accident, sir. The men have found him. He’s –’

Alfred turned towards the library window. Through the open gate in the quickset hedge, the workmen could be seen grouped together, stooping.

‘They found him,’ Alfred said, ‘not to put too fine a point on it, sir – in the ditch. I’m very sorry, I’m sure, sir, but I’m afraid he’s dead.’

CHAPTER 4 (#u8aaa8190-8710-5c81-9876-cf738804c466)

Alleyn (#u8aaa8190-8710-5c81-9876-cf738804c466)

‘There you are,’ said Superintendent Williams. ‘That’s the whole story and those are the local people involved. Or not involved, of course, as the case may be. Now, the way I looked at it was this. It was odds on we’d have to call you people in anyway, so why muck about ourselves and let the case go cold on you? I don’t say we wouldn’t have liked to go it alone, but we’re too damned busy and a damn’ sight too understaffed. So I rang the Yard as soon as it broke.’

‘The procedure,’ Alleyn said dryly, ‘is as welcome as it’s unusual. We couldn’t be more obliged, could we, Fox?’

‘Very helpful and clear-sighted, Super,’ Inspector Fox agreed with great heartiness.