По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

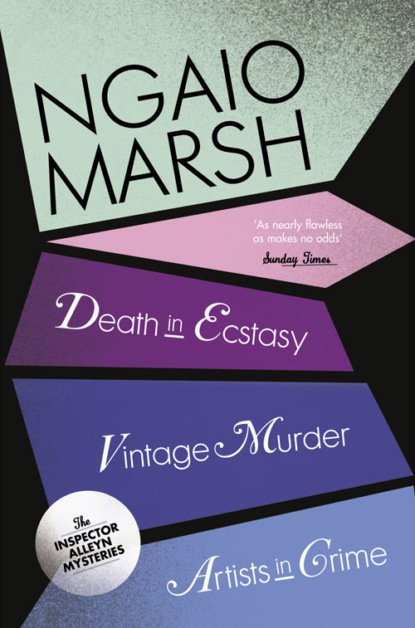

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 2: Death in Ecstasy, Vintage Murder, Artists in Crime

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What do you mean?’ asked Nigel, ‘It’s red. Is it drenched in somebody’s life-blood? Why must you be so tiresomely enigmatic?’

‘Nobody’s being enigmatic. I’m telling you, as Mr Ogden would say. Here’s a bit of cigarette-paper. It’s been doubled over and gummed into a tiny tube. One end has been folded over several times making the tube into an envelope. It has been dyed – I think with red ink. It’s wet. It smells. It’s a clue, damn your eyes, it’s a clue.’

‘It will have to be analysed, won’t it, sir?’ asked Fox.

‘Oh rather, yes. This is the real stuff. “The Case of the Folded Paper.” “Inspector Fox sees red.”’

‘But, Alleyn,’ complained Nigel, ‘if it’s wet do you mean it’s only recently been dipped in red ink? Oh – wait a bit. Wait a bit.’

‘Watch our little bud unfolding,’ said Alleyn.

‘It’s wet with wine,’ cried Nigel triumphantly.

‘Mr Bathgate, I do believe you must be right.’

‘Facetious ass!’

‘Sorry. Yes, it floated upon the wine when it was red. Bailey!’

‘Hullo, sir?’

‘Show us just where you found this. You’ve done very well.’ A faint trace of mulish satisfaction appeared on Detective-Sergeant Bailey’s face. He crossed over to the chancel steps, stooped, and pointed to a sixpenny piece.

‘I left that to mark the place,’ he said.

‘And it is precisely over the spot where the cup lay. There’s my chalk mark. That settles it.’

‘Do you mean,’ asked Nigel, ‘that the murderer dropped the paper into the cup?’

‘Just that.’

‘Purposely?’

‘I think so. See here, Bathgate. Suppose one of the Initiates had a pinch of cyanide in this little envelope. He – or she has it concealed about his or her person. In a cigarette-case, perhaps, or an empty lipstick holder. Just before he goes up with the others he takes it out and holds it right end up – wait a moment – like this perhaps.’

‘No,’ said Nigel, ‘like this.’ He folded his hands like those of a saint in a mediaeval drawing, ‘I noticed they all did that.’

‘Excellent. The flat open end would be slipped between two fingers, and the thing would be held snug. When he – call it he for the moment – takes the cup, he manages to let the little envelope fall in. Not so difficult as it sounds. We’ll experiment later. The paper floats. The folded end uppermost, the open end down. The powder falls out.’

‘But,’ objected Fox, ‘he’s running a big risk, sir. Suppose somebody notices the paper floating about on the top of the wine. Suppose, for the sake of argument, Miss Jenkins or Mr Ogden say they saw it, and Mr Pringle and the rest don’t mention it – well, that won’t look too good for Mr Pringle. If he’s the murderer he’ll think of that. I mean –’

‘I know what you’re driving at, Inspector,’ said Nigel excitedly. ‘But the gentleman says to himself that if anyone notices the paper he’ll notice it too. That will switch it back a place to the one before him.’

‘Um,’ rumbled Fox doubtfully.

‘I don’t think they would see it,’ Alleyn murmured. ‘You say, Bathgate, that during the ceremony of the cup the torch was the only light?’

‘Yes.’

‘Quite so. It’s nearly burnt out now, but I think you will find that when it’s going full blast there will be a shadow immediately beneath it where they knelt, a shadow cast by its own sconce.’

‘I think there was,’ agreed Nigel. ‘I remember that they seemed to be in a sort of pool of gloom.’

‘Exactly. And in addition, their own heads, bent over the cup, would cast a further shadow. All the same, you’re right, Fox. He is taking a big risk. Unless –’ Alleyn stopped short, stared at his colleague, and then for no apparent reason made a hideous grimace at Nigel.

‘What’s that for?’ demanded Nigel suspiciously.

‘This is all pure conjecture,’ said Alleyn abruptly. ‘When the analyst finds traces of cyanide we can start talking.’

‘I can’t see why he’d drop the paper in,’ complained Nigel. ‘It must have been accidental.’

‘I don’t know, Mr Bathgate,’ said Fox in his slow way. ‘There are points about it. No fingerprints. Nothing to show if he’s searched.’

‘That’s right,’ said Bailey suddenly. ‘And he’d reckon the lady’d be sure to drop the cup. He’d reckon on it falling out and getting tramped into the carpet like it was.’

‘Say it stuck to the side?’ objected Fox.

‘Well, say it did,’ said Bailey combatively. ‘What’s to stop him getting it out when they’re all looking at the lady throwing fancy fits and passing in her checks?’

‘Say it slid out on to her lips,’ continued Fox monotonously.

‘Say she drank it? You make me tired, Mr Fox. It wouldn’t slide out, it’d slide back on the top of the wine. Isn’t that right?’

‘Um,’ said Fox again.

‘What d’yer mean “Um”! That’s fair enough, isn’t it, sir?’ He appealed to Alleyn.

‘Conjecture,’ said Alleyn. ‘Surmise and conjecture.’

‘You started it,’ remarked Nigel perkily.

‘So I did. That’s all the thanks I get for thinking aloud. Come on, Fox. It grows beastly late. Shut up your find. We’ll know more about it when the analyst has spoken his piece.’

Fox took the little box from him, shut it, and put it into the bag.

‘What’s next, sir?’ he asked.

‘Why, Mr Garnett’s little bottle. Where is Mr Garnette?’

‘In his rooms. Dr Curtis is there and one of our men.’

‘I wonder if he has converted them. Let us join the cosy circle. You can tackle the vestry now, Bailey.’

Fox, Alleyn and Nigel went up to Father Garnette’s room, leaving Bailey and his satellites to continue their prowling.

Father Garnette sat at his desk which, with its collection of objects de piété, so closely resembled an altar. Dr Curtis sat at the table. A uniformed constable with a perfectly expressionless face stood by Father Garnette’s prie-dieu, furnishing a most fantastic juxtaposition of opposites. They all had the look of persons who have not spoken for a considerable time. Father Garnette was pallid and a little too dignified; Dr Curtis was wan and puffed with suppressed yawning; the constable was merely pale by nature.

‘Ah, Mr Garnette,’ said Alleyn cheerfully, ‘here we are at last. You must long for your bed.’